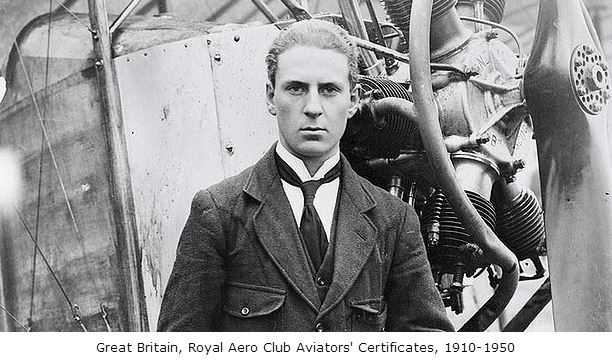

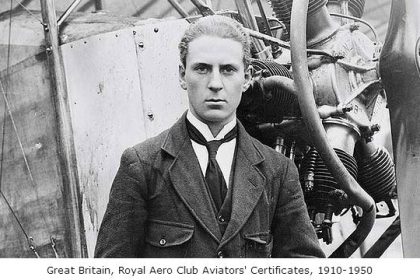

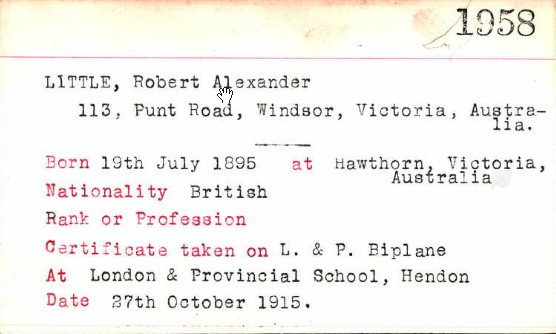

Robert Alexander Little did not come to the war looking for glory, and he did not arrive with the backing of a flying school or a military commission waiting for him. He came because he wanted to fly, because aviation fascinated him long before it became a weapon, and because when the chance did not come easily, he paid for it himself. By the time his life ended in a dark field in northern France in May 1918, Little had become the most successful Australian fighter ace of World War I, with 47 confirmed victories, achieved in barely two years at the front and before his twenty-third birthday. Little was born on July 19, 1895, in Hawthorn, near Melbourne, into a family that valued education and discipline. He was a good student and a strong swimmer. When war broke out in August 1914, he was working in his father’s business as a traveling salesman, but like many young men of his generation, his attention was already drifting upward, toward flight. He tried to enter Australia’s Central Flying School at Point Cook, but with only four places available, he was turned away along with hundreds of others. Rather than accept the decision, Little boarded a ship to England in July 1915 and paid for his own flying lessons, earning his Royal Aero Club certificate at Hendon that October.

Ace Journey of Robert Alexander Little’s First Victories

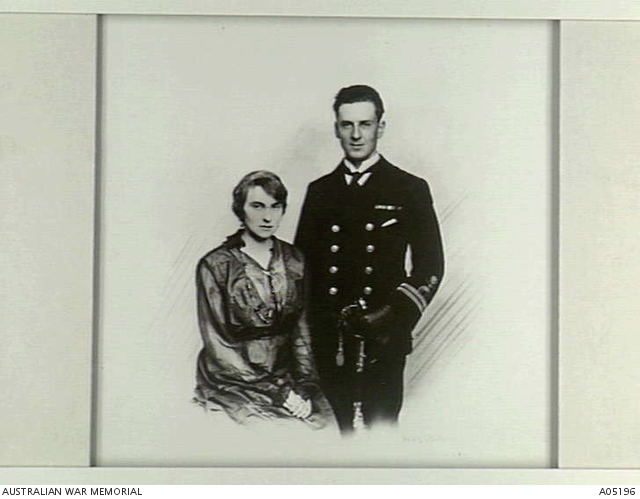

In January 1916, he joined the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) as a probationary flight sub-lieutenant, and almost immediately learned that early aviation demanded physical toughness as much as skill. He suffered badly from air sickness, likely caused by castor oil fumes from rotary engines, but persisted. By June 1916, he was in France with No. 1 (Naval) Wing at Dunkirk, flying Sopwith 1½ Strutters on bombing missions. That same year, in September, he married Vera Gertrude Field in Dover. Little’s real fighting career began when he joined No. 8 Squadron RNAS, known as “Naval Eight,” flying Sopwith Pups over the Western Front. The Pup was light and underpowered, topping out at around 112 mph, but in the hands of an aggressive pilot, it could be deadly. Little scored his first victory on November 23, 1916, destroying a German two-seater near La Bassée. By early 1917, he had four victories and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for conspicuous bravery. His fighting style was unique as he closed in close, sometimes to just 25 yards, held his fire, and shot with precision rather than volume. In December 1916, during an engagement alongside fellow Australian Stanley Goble, Little disappeared after combat and was assumed lost. But he returned later, having landed near Allied lines to clear a jammed gun before taking off again to rejoin the fight. On April 7, 1917, he single-handedly engaged 11 Albatros scouts, which he outflew and outfought for almost 30 minutes.

On April 24, 1917, Little engaged a DFW CV, forcing it to land. He then followed the German aircraft down to claim it as captured and personally take its crew prisoner at gunpoint. Later in April, Naval Eight’s conversion to the Sopwith Triplane saw Little begin to score heavily, eventually registering 24 victories in the Triplane, most of them in a single aircraft, N5493, which he named Blymp, a name later passed on to his infant son. It brought his total up to 28, including twin victories four times in a single day. The pace did not slow when Naval Eight transitioned to the Sopwith Camel. Faster and more dangerous to inexperienced pilots, the Camel demanded constant attention, but Little mastered it quickly. In July alone, he added ten more victories. By the time he was rotated back to England for rest, he had 38 confirmed victories and decorations such as a Bar, a Distinguished Service Cross, the French Croix de guerre, the Distinguished Service Order, and a Bar to the DSO, awarded for repeated acts of daring and aggression in combat. He was promoted to flight commander, though leadership was never his primary instinct, as Little fought best alone. Despite his success, Little was not considered a smooth or elegant pilot as he crash-landed more than once, and his flying could be rough around the edges. But he had extraordinary eyesight, calm nerves, and precise accuracy with his guns. His colleagues remembered him as deadly in the air and gentle on the ground, and a collector of wildflowers. They called him “Rikki,” after Kipling’s mongoose, quick and lethal against larger foes.

Final Flights

In early 1918, Little was offered a desk job, which he refused. In March, he returned to the front with No. 3 Squadron RNAS, commanded by Raymond Collishaw. On April 1, with the formation of the Royal Air Force, the unit became No. 203 Squadron RAF. Now a captain, Little again flew the Sopwith Camel and resumed scoring almost immediately, beginning with a Fokker Triplane on April 1. Over the next seven weeks, he added nine victories, including two on May 22, bringing his total to 47. On April 21, he had been shot down unharmed by German ace Friedrich Ehmann, but even that did not slow him. On the night of May 27, 1918, reports came in of German Gotha bombers operating nearby. Little took off alone into a moonlit sky to intercept them. As he closed on one of the bombers, a searchlight caught his Camel, and a single bullet passed through both thighs. He managed a crash-landing near Nœux, but bled to death before dawn. Whether the shot came from a Gotha gunner or from the ground was never determined. He was twenty-two years old. Little was buried first at Nœux and later reinterred at Wavans British Cemetery. He left behind a widow and a young son, whom Vera raised in Australia, honoring his wish that the child grow up far from war.

Of his 47 victories, 20 were recorded as destroyed, two captured, and 25 out of control, with many more likely uncounted. He remains the highest-scoring Australian ace of World War I. A propeller blade from his Triplane was turned into a clock by his fellow officers and sent home to his widow. A Sopwith Pup associated with his unit survives in a museum. A building at the Australian Defence Force Academy bears his name. In the Aces series, Robert Little stands as a reminder that the First World War’s air war was not won only by famous names, but also by young men who paid their own way into the sky, and disappeared before history had time to catch up with them.