More than a million Indians served across the battlefields of World War I, fighting in trenches, deserts, mountains, and seas far from home, but only a very small number ever made it into the air. Among them was a young man from Bengal, Indra Lal Roy, who would become India’s first fighter ace before his twentieth birthday, flying and fighting in one of the most dangerous periods in aviation history. Roy was born on December 2, 1898, in Calcutta, but his family moved to London in 1901, placing him at the center of the British Empire just as aviation itself was being invented through trial, error, and loss.

Roy was still a schoolboy when the war broke out in July 1914, and like many young men of his generation, he wanted to take part in it. Driven by his commitment, he joined the cadet force at St Paul’s School in Hammersmith and even attempted to contribute through engineering, designing a trench mortar and sending its plans to the War Office. His academic promise earned him a scholarship to Oxford, but Roy had already decided that his future was not in classrooms or courtrooms, like his father, a respected barrister, but in the air.

Early Days of Indra Lal Roy’s Service

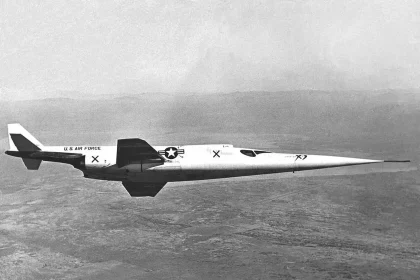

When Roy first applied to the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), he was rejected due to defective eyesight, a decision that would have ended the dream for most teenagers. But Roy instead sold his motorbike to pay for a second opinion from a leading eye specialist. He passed the examination, appealed the decision, and on July 5, 1917, at just 18 years old, was commissioned into the RFC and posted to No. 56 Squadron, one of Britain’s elite fighter units. The squadron flew the Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5, later the S.E.5a, one of the best fighters of the war. Capable of speeds around 120 miles per hour at 15,000 feet, armed with a synchronized .303 Vickers machine gun and a Lewis gun mounted above the wing, the aircraft rewarded disciplined flying but punished mistakes, and Roy, still barely out of school, found himself flying it over France.

Among fellow pilots, Roy quickly earned a reputation for energy and fearlessness, sometimes pushing the aircraft harder than experience would normally allow. But that came at a cost on December 6, 1917, when his aircraft was shot down by a German fighter and crashed, leaving him badly injured and unconscious. His injuries were so severe that he was declared dead, moved to a hospital morgue, and laid out among bodies, only to regain consciousness and begin pounding on the door while shouting in broken French for help. To their surprise, the hospital staff found themselves face to face with a pilot who had quite literally returned from the dead. Roy was sent back to England to recover. During his recovery period, he filled notebooks with aircraft sketches and technical drawings, many of which survive today. Doctors declared him unfit to fly, but Roy refused to accept it and repeatedly requested his superiors to take him back into service until they finally agreed. In June 1918, he returned to active duty, this time with No. 40 Squadron of the newly formed Royal Air Force, created just two months earlier through the merger of the RFC and the Royal Naval Air Service.

From Declared Dead to Becoming an Ace

This second chance transformed Roy, who returned more focused, and within weeks, he scored his first aerial victory over northern France. Roy’s first confirmed victory came on July 6, 1918, when he shot down a German Hannover C two-seater over Drocourt. Two days later, on the morning of July 8, he destroyed three enemy aircraft within just four hours. Among those victories were two Hannover Cs and a Fokker D.VII, one of Germany’s most capable fighters, an aircraft produced in large numbers toward the end of the war and respected by pilots on both sides. On July 13, Roy added a Pfalz D.III and another Hannover C to his tally, and with crossing five confirmed kills, he officially became a flying ace. There was a brief pause after that milestone. On July 15, he shot down two more Fokker D.VIIs, followed by a DFW C.V reconnaissance aircraft on July 18 and another Hannover C the very next day.

In just over two weeks, Roy destroyed ten enemy aircraft, becoming India’s first flying ace after barely 170 hours of total flying time. But these victories marked the final chapter of his combat success. On July 22, 1918, Roy’s formation of three S.E.5a aircraft was attacked by four Fokker D.VIIs. Although British pilots fought back and managed to shoot down two of the attacking fighters, Roy’s aircraft was hit and burst into flames. He crashed into German-held territory of Carvin, ending his life at just 19 years old. In September 1918, Roy was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, becoming the first Indian to receive the honor. Roy was buried at the Estevelles Communal Cemetery in France, his grave marked with a Bengali inscription that reads, “The grave of a courageous warrior; respect it, do not touch it.”

His legacy lived on beyond the war, not only in memory but in family, as his nephew, Subroto Mukerjee, would later fly fighters in World War II and go on to become the first Chief of Air Staff of the Indian Air Force. In the Aces series, stories such as that of Indra Lal Roy remind us that World War I was not only fought by empires, but by individuals from across the world, young men who learned to fly and fight at the same time.

Related Articles

Kapil is a journalist with nearly a decade of experience. Reported across a wide range of beats with a particular focus on air warfare and military affairs, his work is shaped by a deep interest in twentieth‑century conflict, from both World Wars through the Cold War and Vietnam, as well as the ways these histories inform contemporary security and technology.