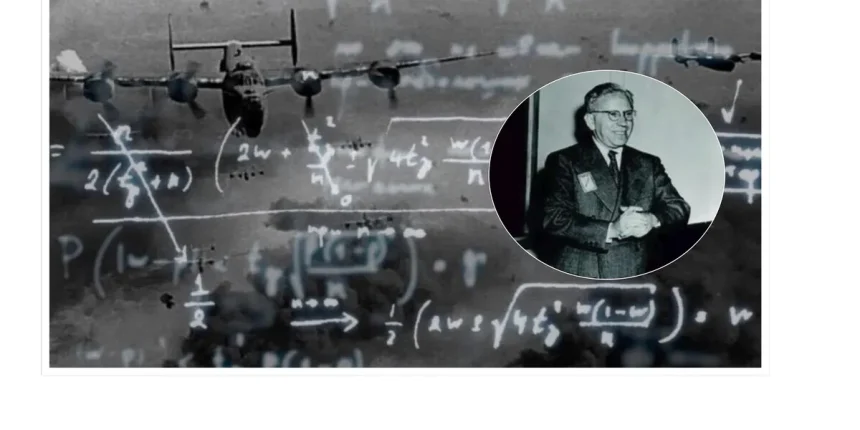

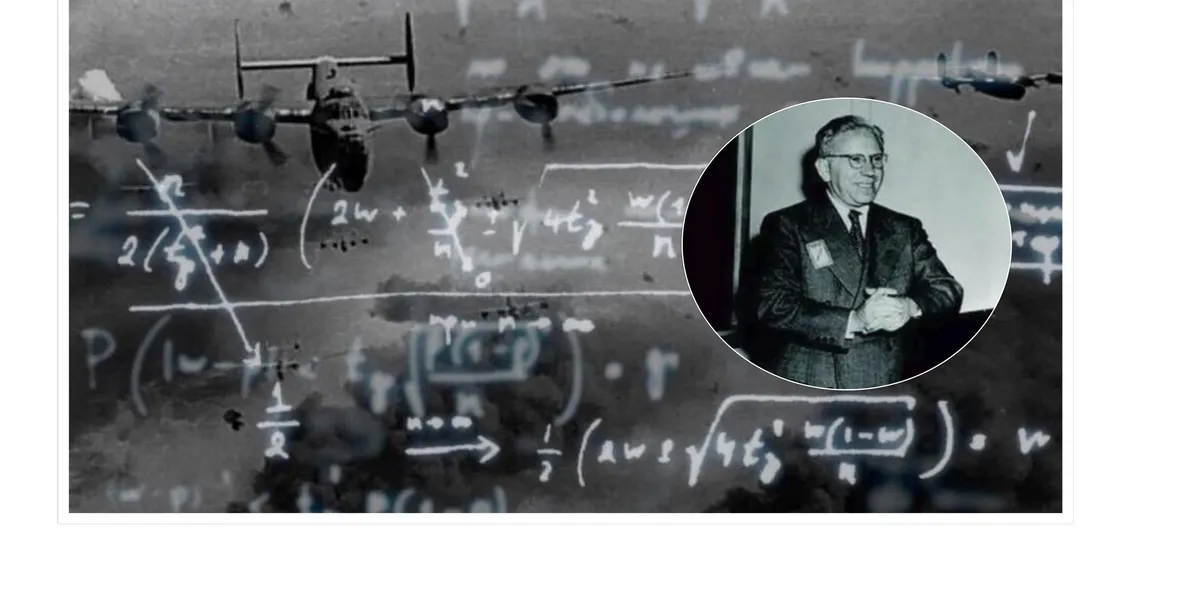

Early in World War II, the Navy and the Army Air Corps were suffering what officials considered to be an unacceptable number of lost bombers and their crews to enemy fire. As a result, they were looking for ways to cut their losses. That project fell to a group of statisticians at Columbia University called the Statistical Research Group (SRG). They were charged with finding ways to solve complex military-related problems using mathematical methods. The head of the group was an American economist and statistician named W. Allen Wallis, the SRG’s director, who described the group as “the most extraordinary group of statisticians ever organized, taking into account both number and quality.” Particularly highly regarded among this group was a Hungarian mathematician and statistician named Abraham Wald.

A Place for Numbers

Wald was born in 1902 in Kolozsvár, Transylvania, in the Kingdom of Hungary. He was born into a Jewish family, who home-schooled him until he went to college. He graduated with a degree in mathematics from King Ferdinand I University in 1928 and graduated with a Ph.D. degree in mathematics from the University of Vienna in 1931. Austria in the 1930s was not a good place for a Jew, especially when the political and economic situation is considered. As a result, Wald had problems finding a job, despite his obvious gifts for translating complex statistical problems into real-world solutions. Despite these issues, Wald eventually found a job working for economist Oskar Morgenstern at the Austrian Institute for Economic Research in Vienna. At the same time, Wald was asked to work at the Cowles Commission for Research in Economics in Colorado Springs, Colorado. At first, Wald had trouble deciding whether to take the Cowles job, but when Austria was annexed into Nazi Germany in 1938, he quickly decided to take the job in the United States.

Wald had only worked at Cowles for a few months when he received yet another offer, this time as a professor of statistics at Columbia University in New York. He accepted the offer, moved with his family to New York City, and became part of the Statistical Research Group (SRG) at the university, a decision that would change the trajectory of his life as well as military aviation. It wasn’t long after Wald started at SRG that a problem arose. As a citizen of a country that was considered hostile to the United States, technically, Wald was unauthorized to work on the projects he had taken part in. Soon, a joke started that anything he had written had to be taken from him so he couldn’t read it. The situation might have been absurd, but it made a good point. For this reason, Wald’s application for citizenship was moved up on the docket so he could become an American citizen in a matter of days, not months.

Survivorship Bias

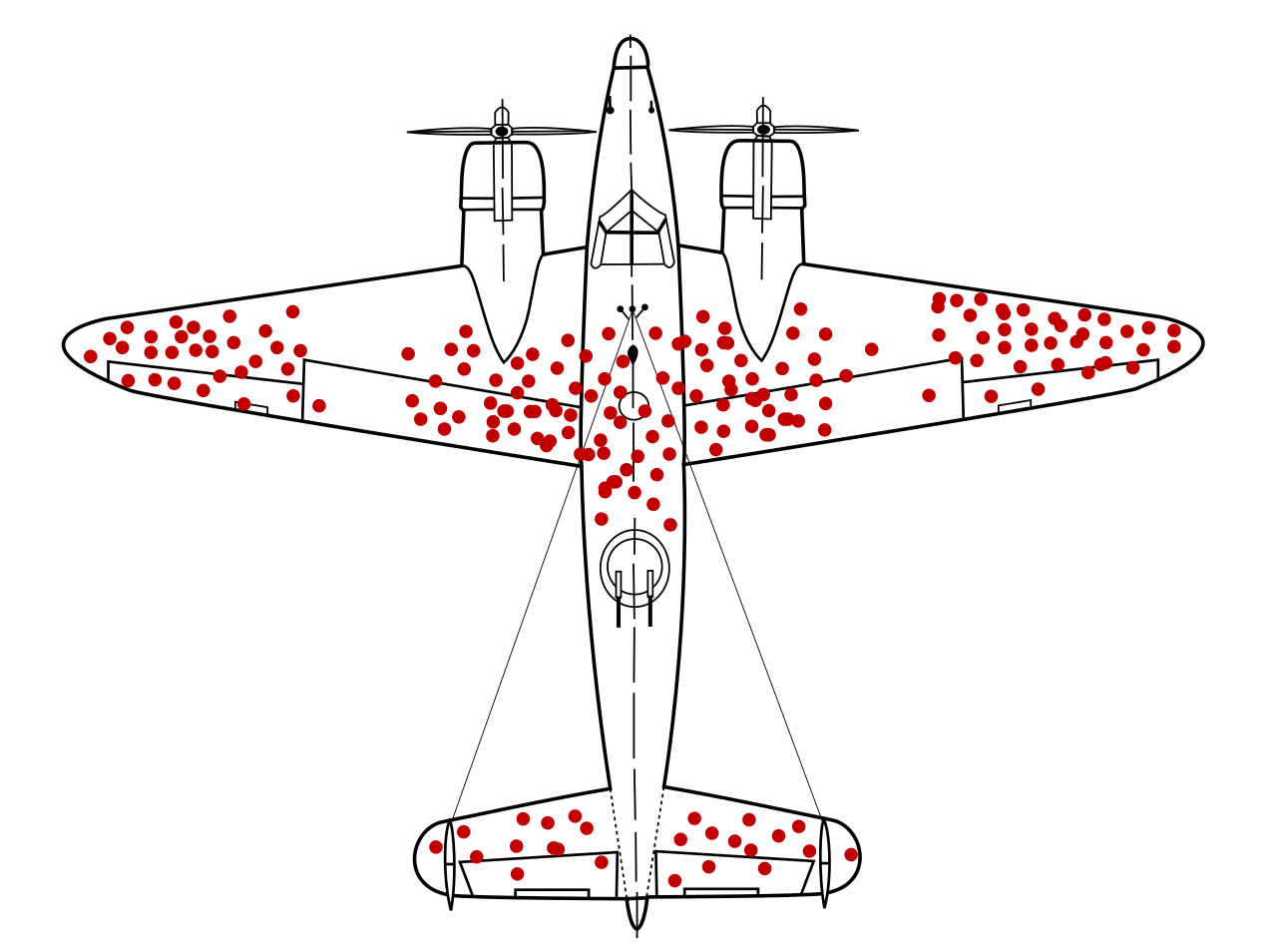

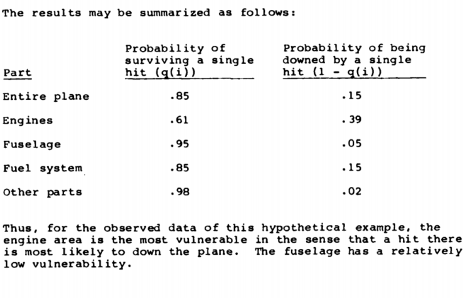

It wasn’t long before Wald was asked to take on a project that his unique gift of statistical research would prove invaluable. It also showed that he could make abstract problems and use statistics to create practical solutions to real-world problems. The Navy and the Army Air Force were losing large numbers of aircraft due to enemy fire. As a result, the authorities wanted to find out how they could best armor their planes to decrease their losses. They were cautious in how they did this because more armor on an aircraft would make it heavier, not to mention harder to control due to shifts made in its axis. As a result, authorities decided to armor the areas of each plane only where damage had occurred. But Wald had another idea. It might have been counterintuitive at the time, but it worked. Why not analyze where on an aircraft survivable hits had been taken and armor those places where damage on aircraft that had not hit? Obviously, all aircraft that were shot down could not be utilized for this purpose, but Walt took a different approach. He asked those who worked with the returning aircraft to plot where on each aircraft damage had occurred, but it was able to return to its base. The result was what might be called a “scattergram” of damage. Below is the graphic they came up with.

It is obvious from this graphic that certain areas were more prone to damage than others, separating those that survived their damage from those that did not. The meaning of this being that more armor should be applied to areas of the aircraft that were not affected by those that returned to base (i.e., mid-wings, rear and forward airframe, etc.). Bullet holes were never found in certain areas of planes, such as the engines, since rounds that had been shot there had not returned. Wald surmised correctly that bullets were actually hitting the aircraft all over, but since the ones hit in the most vulnerable areas didn’t come home, the data incorrectly suggested that these areas weren’t being hit at all. What those less qualified to evaluate the data didn’t understand was that the empirical evidence was based only on data obtained on planes that survived attacks.

The only aircraft that could be inspected were those that survived and returned home — the survivors. The aircraft that were being shot down weren’t available for inspection. This difference created what was eventually called the “survivorship bias.” The massive amount of damage to bombers’ fuselages and wings was actually evidence that these areas did not need reinforcing, since they were clearly able to take a large amount of damage without being brought down. As a result, Wald concluded, the armor should be placed on the areas that received the least damage. It might seem counterintuitive, but he was right. The military took Wald’s advice and began increasing armor protection over these more vulnerable areas of aircraft. Statistics on how many lives this saved during the war or since then are difficult to determine, but there are likely many airmen alive today who would not be if Wald hadn’t made his contributions to the survivorship bias theory. Wald continued to make his remarkable contributions to statistical research until he was invited to give a lecture tour at the request of the Indian government in 1950. Wald and his wife were killed in a plane crash near the Rangaswamy Pillar in the northern part of the Nilgiri Mountains in southern India on December 13, 1950. Their two children were at home when the crash occurred. One of the children was Robert Wald, who is today a noted physicist.

After his death, Wald was widely criticized by several scholars, most notably Sir Ronald A. Fisher, who attacked him for being a mathematician lacking direct scientific experience. Fisher particularly criticized Wald’s work on the design of experiments and alleged ignorance of the basic ideas of the subject, as set out by him and Frank Yates. Wald’s work was defended by Jerzy Neyman the next year. Neyman explained Wald’s work, particularly with respect to the design of experiments. Lucien Le Cam credits him in his own book, Asymptotic Methods in Statistical Decision Theory: “The ideas and techniques used reflect first and foremost the influence of Abraham Wald’s writings.”

Net Effect

The accuracy of Wald’s work on aircraft survivability has been supported by the fact that it was used to benefit aircraft in not only World War II, but also in Korea and Vietnam. His work was initially published in a series of SRC memoranda and reissued by the Center for Naval Analyses. These memoranda were used to estimate the vulnerability of aircraft, using data obtained from survivors. Wald’s work was published in 1981 and reprinted by the Center for Naval Analyses, indicating its continued relevance and accuracy in the field of statistical analysis and decision-making.

Michael W. Michelsen, Jr., is a freelance writer in Riverside, California. An Air Force brat, Michael grew up on more bases than he cares to admit, but he loved every day of it. Among the benefits he most cherishes is the love of aviation that continues to this day.