In discussing some of the most iconic American military aircraft of the Jet Age, certainly one of the most iconic of these has to be the Convair B-58 Hustler, the first American supersonic bomber. With its large delta wing and external pod for carrying both bombs and fuel, the Hustler was developed to fulfill the need for a high-altitude, high-speed bomber capable of flying long distances from the United States to the Soviet Union and back. Developed from Convair’s prior experience in delta winged aircraft, such as the XF-92 and the F-102 Delta Dagger, the Hustler was one of the most sophisticated aircraft of its day, featuring a three-man crew consisting of a pilot (aircraft commander (AC)), navigator/bombardier, and defense systems operator (DSO) in a tandem seating arrangement with individual escape pods, a complex guidance navigation and bombing system with bombing radar, terrain-following radar, radar-warning receiver, a slender “coke bottle” fuselage adapted from the redesigned F-102 and the F-106, and used heat-resistant aluminum honeycomb panels in its construction. The aircraft would also set numerous records for long endurance supersonic flights at both low and high altitudes.

During its ten-year service life from 1960 to 1970, the Convair B-58 Hustler was operated by two wings of the U.S. Air Force’s Strategic Air Command (SAC); the 43rd Bombardment Wing, based at Carswell Air Force Base (now Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Fort Worth), near Fort Worth, Texas, from 1960 to 1964, and from Little Rock AFB, Arkansas, from 1964 to 1970; and the 305th Bombardment Wing, based at Bunker Hill AFB (later renamed Grissom AFB; now Grissom Air Reserve Base), near Bunker Hill, Indiana, from 1961 to 1970. However, the rapid changes in aerospace technology on both sides of the Iron Curtain, combined with the Hustler’s expense in manufacturing and its inability to adapt as readily to new mission parameters for which it had not been designed for would mean that one of the sleekest bombers of the Jet Age would have a short operational life, with the last examples being retired to the Boneyard at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base near Tucson, Arizona. Today, of the 116 airframes produced at Convair’s Fort Worth, Texas plant, just a few examples remain in existence across the United States. These are those examples, and the stories of how they have survived to the modern day.

YB-58A/RB-58A/TB-58A 55-0663

The oldest of the surviving B-58 Hustlers is the fourth ever example built, and it can be found at one of the bases from which it spent much of its operational career. Manufactured as construction number 4 at Convair’s Plant 4 in Fort Worth, this aircraft was accepted into the USAF as YB-58A serial number 55-0663, and was only the second of the 11 YB-58 pre-production prototypes of the Hustler built. On August 12, 1957, the aircraft made its first flight and was assigned to the 6592nd Test Squadron at Carswell AFB in September 1957, but was also flown by test pilots from Convair. YB-58A 55-0663 would be used for extensive testing in the external, jettisonable pod that added to the Hustler’s unique profile. On September 20, 1957, the aircraft was the first B-58 to drop its pod at supersonic speeds, and three months later, on December 30, 55-0663 became the first B-58 to drop its external pod while flying at Mach 2, with both of these tests proving that the aircraft could safely jettison its fuel/bomb pod at the speeds it would operate at. In 1958, YB-58 55-0663 was converted into the first RB-58A reconnaissance variant, and was used for testing the reconnaissance pod, which would be jettisoned after transferring the film from its camera into the aircraft to return to base. By 1962, 55-0663 was loaned from the 6592nd Test Squadron to NASA for use in gathering flight test data for the planned American project to develop a Supersonic Transport (SST), which was ultimately cancelled long after 55-0663’s involvement due to a myriad of issues beyond the scope of this article.

By 1963, 55-0663 became one of eight YB-58A aircraft to be converted into a TB-58A trainer to instruct new pilots in operating the Hustler, with the navigator/bombardier station being modified with a second set of pilots controls, and the defensive systems operator’s position was also filled by another pilot, but without flight controls, with this B-58 student monitoring the flight procedures before he would be instructed to fly the aircraft for himself. TB-58A 55-0663 was assigned to the 305th Bomb Wing at Bunker Hill Air Force Base, near the town of Bunker Hill, Indiana (in 1968, Bunker Hill AFB would be renamed Grissom AFB in honor of Virgil “Gus” Grissom, Air Force pilot, the second American astronaut to enter space, and member of the ill-fated Apollo 1 mission, who originally hailed from Mitchell, Indiana). TB-58A 55-0663 would continue to operate routine training missions until January 1969, when an oxygen leak combined with an electrical spark resulted in a fire in the cockpit. Fortunately, no injuries were reported in this incident, but with the B-58 program as a whole winding down to decommissioning with the year, it was decided that although the aircraft would not fly again, it would at least be restored to static display condition and remain at Grissom Air Force Base to be a gate guardian, along with several other retired aircraft on base.

For the next 18 years, TB-58A 55-0663 stood silent watch over Grissom AFB, its nose gear resting on a concrete plinth while the main gear stood level. By 1981, the Grissom Air Museum, was founded by seven local veterans, including Air Force veteran and businessman John Crume, with the goal of preserving the historic aircraft on display at Grissom, and by 1987, TB-58A 55-0663 had been moved with the rest of the aircraft to a corner of the base right on the offramp for U.S. Route 31, but formally on long-term loan through the National Museum of the USAF at Wright-Patterson AFB. Over the years, new aircraft went on display next to the aircraft, while a few others left for other museums. However, the aircraft that remain at Grissom have been in the weather now for decades, and like any museum that relies on volunteers funded by donations, it is difficult to maintain aircraft through the changing seasons on a yearly basis. In recent years, though, this is set to change for the museum’s Hustler, the oldest one in existence.

In November 2025, construction began on the Grissom Air Museum’s Capt. Manuel Cervantes Building to house TB-58A Hustler 55-0663 in an indoor facility for the first time since it was retired from active service. The museum is named in memory of navigator/bombardier Captain Manuel “Rocky” Cervantes, who killed as a result of a takeoff accident on B-58A Hustler 60-1116 during a Minimal Interval Takeoff (MITO) in blizzard conditions on December 8, 1964, while carrying four B43 thermonuclear bombs and one B53 thermonuclear bomb, while pilot Leary Johnson and DSO Roger Hall survived. The new building named in Captain Cervantes’ honor will be constructed in three phases. As of February 2026, phase one is largely complete, and TB-58A Hustler 55-0663 has already been installed in the new building. The next phase will consist of the outfitting of climate control facilities to prevent further deterioration of the aircraft and have the building operate in all seasons. Finally, the third phase of the project will see the building being outfitted with educational and immersive displays on the B-58 Hustler, with an emphasis on the flight crews who operated the B-58. The Grissom Air Museum expects the total cost to amount to $750,000, but has already raised more than $455,000 for the project, and it is hoped that the building will be complete and ready for the public by 2027. To learn more about the project, visit the webpage on the Grissom Air Museum’s website HERE. For the museum’s main website, visit this link HERE.

YB-58A 55-0665

Standing over the Mojave shrubs near the southern edge of Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards Air Force Base, California, are the remains of the second-oldest remaining B-58 Hustler, albeit in a severe derelict condition, a skeleton of its former self. This is YB-58A 55-0665, construction number 6. After being completed at Plant 4, YB-58A 55-0665 made its first flight on September 28, 1957. On February 14, 1958, the aircraft arrived at Edwards AFB to begin flight tests with the Air Research and Development Command (ARDC). 55-0665 would spend the entirety of its Air Force service life as a testbed for various flight systems.

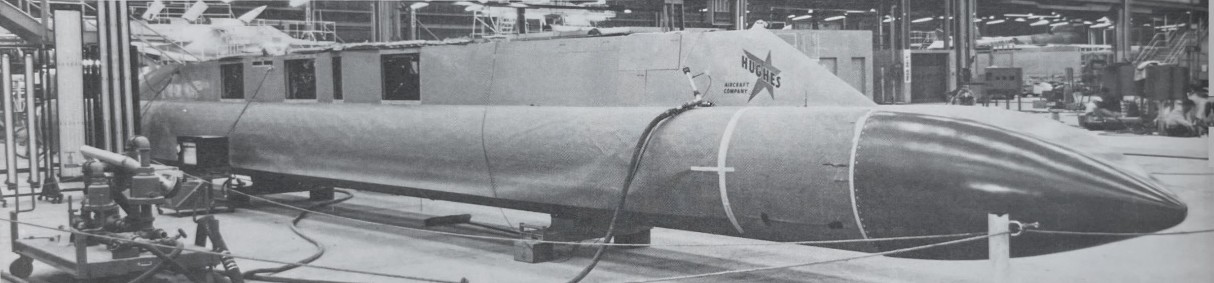

In 1958, Hughes Aircraft of Culver City, California, began work on a new radar/fire control system to be incorporated with the new GAR-9 air-to-air missile. This was the AN/ASG-18 Fire Control System, the first Pulse-Doppler radar system, which used both pulse-timing techniques and the Doppler effect to determine the range and velocity of a selected target. The massive system, weighing 2,100 pounds (950 kg) also featured a look-down/shoot-down capability, a track-while-scan radar, and was paired with an infrared search and track (IRST) system, and the AN/ASG-18 had an estimated range of between 200–300 mi (320–480 km). This was to be used in the proposed North American XF-108 Rapier interceptor, and on October 17, 1958, Convair received a contract from Hughes and the USAF to manufacture two external pod to house the GAR-9 missiles, which would later be reclassified as the Hughes AIM-47 Falcon, and modify a B-58 to serve as a testbed for the AN/ASG-18. YB-58A 55-0665 was selected to be that aircraft, and on February 15, 1959, the aircraft had these modifications installed at Edwards AFB.

The installation of the radome for the AN/ASG-18 Fire Control System lengthened YB-58A 55-0665 added nearly seven feet to the aircraft’s length, and the new distinctive shape of YB-58A 55-0665’s nose would lead to the aircraft being given the name Snoopy, after the iconic character from the Peanuts comic strip. However, before YB-58A Snoopy had ever flown with the new radar system, the XF-108 program was cancelled before a single example was built, in large part due to the program becoming too costly. However, the AN/ASG-18 system would be reworked to be used on a new interceptor, the Lockheed YF-12, which was an adoption of the Lockheed A-12 reconnaissance aircraft, capable of reaching speeds above Mach 3, and which was further adapted into the SR-71 Blackbird. As Lockheed’s Skunk Works division worked under tight secrecy on the YF-12, test pilots and engineers at Edwards AFB flew YB-58A 55-0665 in extensive flight tests with the AN/ASG-18 Fire Control System from 1960 to 1963, when the YF-12 made its first flight on August 7, 1963. In addition to the new radome in the nose, 55-0665 would fly with a special pod mounted to its underside, carrying the payload of AIM-47 missiles, and would fire AIM-47s at target drones, from unmanned Lockheed QF-80 Shooting Stars to Vought Regulus cruise missiles.

By February 1964, though, the development of the AN/ASG-18 Fire Control System and the AIM-47 Falcon were exclusively limited to further evaluation with the Lockheed YF-12, and YB-58A 55-0665 Snoopy was no longer needed for launching AIM-47 Falcons. Following this, YB-58A 55-0665 was stricken from the inventory, stripped of all instruments and engines (though it would retain the radome exterior, and rolled out into the desert within Edwards AFB, being placed on the photo range next to an asphalt pad for satellite and reconnaissance aircraft to calibrate their cameras with, and the hulk of the aircraft has remained there for about sixty years now.

With the establishment of the Flight Test Museum Foundation in 1983, followed by the opening of the museum building in July 2000, the wreck of the YB-58A Hustler Snoopy has been listed in the museum’s inventory, along with several other aircraft currently on the photo range such as the two Northrop X-21 aircraft, but even with the planned expansion of the museum to a more publicly accessible location just outside the West Gate of Edwards AFB (see our previous posts on this museum HERE), it seems unlikely that 55-0665 will be leaving its spot in the desert anytime soon, and even if it were to be dragged out, it is even less likely that given the finite resources of the Flight Test Museum being dedicated to their current efforts to complete the new facility and to restore other, more complete, aircraft in their collection, that a restoration will occur, but given enough resources in time, money, and manpower, it is not impossible, even if it remains a daunting task. Photos of the aircraft can be seen HERE and HERE.

YB-58A Hustler 55-0666

About 230 miles north of Edwards Air Force Base, Castle Airport, formerly Castle Air Force Base, is home to the largest air museum in California’s Central Valley, the Castle Air Museum. We have previously covered several aircraft on display and under restoration at Castle, including this particular B-58 Hustler, YB-58A 55-0666. (See our previous article on this aircraft HERE). Built as construction number 7, YB-58A 55-0666 made its first flight on March 20, 1958. Shortly after this flight, the aircraft was retained for additional flight tests with Convair, being fitted with an experimental General Electric YJ79-GE-5 jet engine mounted on a special centerline pod. On November 8, 1958, 55-0666 flew for 32 minutes at a sustained Mach 2 velocity with its YJ79-GE-5 engine, along with its four stock J79 engines. Though the aircraft was formally transferred to the US Air Force on April 29, 1959, 55-0666 remained with Convair for further testing and evaluation, and was later redesignated as a YRB-58A on May 1, 1959.

On August 16, 1962, the aircraft established an endurance record for the B-58 early test program by flying continuously for 11 hours and 15 minutes. In November of 1962, YRB-58A 55-0666 was reassigned to the 6510th Operational Maintenance Squadron of Air Force Systems Command at Edwards Air Force Base, California, for further testing. In May 1964, 55-0666 was reassigned to the 3345th Maintenance and Support Group of Air Training Command at Chanute AFB in Rantoul, Illinois. By now, the aircraft had been grounded for use as an instructional airframe, and as such, it was redesignated as a GRB-58A.

As the B-58 Hustlers were on the cusp of being phased out of operational service, GRB-58A 55-0666 was stricken from the USAF inventory in 1967, and the personnel at Chanute had it placed on outdoor display at the base’s air park, along with several other aircraft, including a Convair B-36 Peacemaker. Around this time, Chanute AFB’s air park had a policy of painting their aircraft to represent different aircraft to their actual identities. In the case of GRB-58A 55-0665, it was painted to represent B-58A Hustler 61-2059 Greased Lightning, which set a nonstop speed record from Tokyo to London (more on that aircraft later in the article). By the mid-late 1980s, several military bases across the United States were deemed no longer economically feasible to operate, as the Cold War was now beginning to thaw out with the impending collapse of the Soviet Union. Chanute Air Force Base was one of these bases, and on September 30, 1993, Chanute Air Force Base, then America’s third-oldest air base, formally closed after 75 years of service from 1917. As the former base was parceled off to real estate and commercial development, the Octave Chanute Aerospace Museum was formally established on October 8, 1994, to preserve aircraft formally displayed in the base’s air park, taking up residence inside the former Grissom Hall, which served as the former missile maintenance training facility at Chanute.

For more than 20 years, YB-58A Hustler 55-0666 was displayed inside Grissom Hall without engines, where the airframe regained her correct serial number on the tail, but retained its Greased Lightning nose art. Unfortunately, 55-0666 received damage when staff attempted to move the bomber with its main landing wheels locked, fracturing the nose gear. The aircraft would be held up by a wooden frame to keep the nose secure. Sadly for the staff at the Chanute Air Museum, the Village of Rantoul announced in 2015 that it could afford no longer to pay the museum’s utilities, and since the museum did not generate enough revenue from visitors to come up with additional funds, the museum made the difficult decision to permanently close, with the final day for the museum being November 1, 2015. Since most of the aircraft, including B-58 Hustler 55-0666, were on long-term loan from the National Museum of the United States Air Force, several affiliate museums across the country were able to work with the NMUSAF to bring individual aircraft from Chanute to their museums, though several aircraft displayed outdoors were unfortunately scrapped onsite. Given the rarity of the Convair B-58 Hustler among surviving airframes, 55-0666 became highly sought after, and in 2016, it was announced that YB-58A Hustler 55-0666 would find a new home at the Castle Air Museum in Atwater, California, where another aircraft formerly displayed at Chanute, Convair RB-36H Peacemaker 51-13730, was already on display after it was transported in sections by rail from Chanute to Castle for reassembly between 1992 and 1994 (more on that story in these articles HERE and HERE).

From 2016 to 2017, YB-58A Hustler 55-0666 was carefully disassembled at Chanute and loaded on oversize truck trailers hauled by Worldwide Aircraft Recovery of Bellevue, Nebraska, one of the most experienced firms in moving aircraft across the United States. On September 25, 2016, the first truckloads of parts from Hustler 55-0666, including the Number 1 and 4 engine pods with afterburner sections and nozzles, nose radome, and other assorted panels, arrived at Castle Air Museum’s restoration hangar. By April 2017, ground at Castle was prepared to place the Hustler between the museum’s Boeing B-52 Stratofortress and Fairchild C-123 Provider, and on August 18, 2017, the fuselage and wings of 55-0666 arrived at Castle to be reassembled onsite. Since then, the aircraft has been slowly coming together, as the aircraft needed to be treated for corrosion before reassembly could begin. After the wings were reattached in September 2017, 55-0666’s tail and landing gear were reattached in November, and in September 2018, a new nose gear was obtained from its sister ship, YB-58A 55-0665, down at Edwards AFB.

All the while, parts of the aircraft such as the elevons that had been corroded were repaired and refabricated. In March 2020, the nose radome was refitted to the aircraft, and by 2021, the two inboard engine nacelles had been reinstalled, but the outboard nacelles would not be reattached until 2024. According to restoration volunteer Bill Emery, who spoke about the B-58 on the museum’s YouTube page (see this video HERE), the museum hopes to have the aircraft painted “within the next year or two”, with the goal of painting the aircraft in the colors of the Convair test program on the pre-production test aircraft such as YB-58A 55-0666, were they were painted in a striking red, white and silver scheme. There are also preliminary plans to outfit the cockpit, which is currently stripped of instruments, with the goal of having the aircraft ready at some point for the museum’s Open Cockpit Day events. While 55-0666 still has a long way to go, the Castle Air Museum’s dedicated volunteers have made steady progress, and the aircraft stands in good company with dozens of other aircraft on the grounds of one of Strategic Air Command’s largest bases on the West Coast.

YB-58A/TB-58A 55-0668

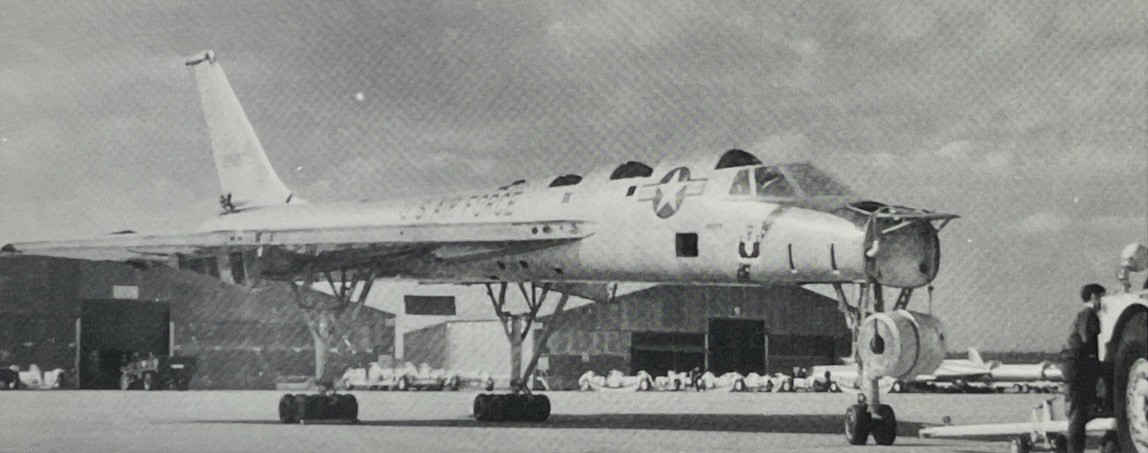

On the grounds of Little Rock Air Force Base, Arkansas, one of the three bases that provided a home for one of the two operational bomb wings with B-58 Hustlers, sits a surviving Hustler that arguably did just as much traveling after it retired than during its operational service. Built at Convair’s Ft. Worth Plant 4 as YB-58A construction number 11, 55-0668 was assigned to the 6592nd Test Squadron at Carswell AFB, TX for use in several experiments, largely around radar reconnaissance pods. One was a centerline pod fitted with the Hughes AN/APQ-69 side-looking airborne radar (SLAR), which featured a 50 foot antenna. YB-58A 55-0668 took the AN/APQ-69 pod into the air for the first time on December 24, 1959, and would eventually conduct around 25 test flights with the device. Tests showed that the AN/APQ-69 had a range of about 50 miles with a resolution of 10 feet, but the pod was not very aerodynamic, and only got optimal results at subsonic speeds, which presented issues for the supersonic B-58, and the system was removed from 55-0668. During the test phase, though, YB-58A 55-668 had been making both “Wild Child II” and later “Peeping Tom” by the crews who worked on it during the AN/APQ-69 program. Shortly after the conclusion of the Hughes AN/APQ-69 program, 55-0668 underwent modifications for being fitted with a new pod for the Goodyear AN/APS-73 Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) system in June 1960. Also known as the XH-3, this so-called “Quick Check” radar was capable of terrain mapping that could scan from both sides of the aircraft and had a range of 80 nautical miles with a resolution of 50 feet. Because of the AN/APS-73’s smaller size, the special pod could also carry fuel to add to the aircraft’s range. 55-0668 was also fitted with a new radome nose with a Raytheon forward-looking radar, and the navigator/bombardier’s station was fitted with new instrumentation for the new radar system.

By May 1961, 55-0668 was delivered for flight testing with the Goodyear AN/APS-73 Quick Check system. As testing continued into 1962, 55-0668 would gain the unique distinction of being the only Convair B-58 Hustler to enter a conflict environment. For thirteen days in October 1962, the world stood on the brink of nuclear Armageddon as the United States and the Soviet Union prepared for war over Soviet missiles deployed to Cuba. During that time, 55-0668, still fitted with its Goodyear AN/APS-73 radar pod, was sent out on a radar reconnaissance mission over Cuba. Though the flight was routine, it represented the only time a B-58 Hustler flew into a conflict zone. Much like the Hughes system before, though, the Goodyear radar system’s best results happened at subsonic speeds, which lessened the efficiency of the aircraft designed to fly for long duration at supersonic speeds. Shortly thereafter, the Goodyear AN/APS-73 was retired, and though YB-58A 55-0668 had been earmarked for conversion to the General Electric J79-GE-9 engine for the planned B-58B program, the cancellation of the B-58B would see 55-0668 being converted into one of the eight TB-58As trainers.

Shortly after its conversion to a TB-58A, 55-0665 was assigned to the 43rd Bombardment Wing at Carswell AFB, where much of its prior flight testing already occurred. In September 1964, the 43rd Bomb Wing was transferred to Little Rock AFB, and for the next six years, TB-58A 55-0668 was used in routine training flights up to the end of the operational service of the Convair B-58 Hustler program. With the retirement of the Hustler from the USAF in 1970, TB-58A 55-0668 made its final flight on January 16, 1970, when it was flown to Davis-Monthan Air Force Base near Tucson, Arizona, for desert storage at what was then the Military Aircraft Storage and Disposition Center (MASDC), better known as the Boneyard. From 1970 to 1977, most of the B-58 Hustler fleet lay in wait under the desert sun, but in 1977, nearly all of the B-58s were sold for scrap to a Tucson-based recycling company, Southwestern Alloys. However, 55-0668 survived the scrapper’s torch (see this photo of the aircraft at Davis-Monthan in 1980 HERE), and with the news that one Hustler remained in the Boneyard, a group of retired Convair engineers sought to save the old Hustler and return it to its birthplace of Fort Worth for display in a new museum being established by the Museum of Aviation Group (MAG).

However, the same engineers were also busy in their efforts to rescue another Convair bomber, B-36J Peacemaker 52-2827 “City of Ft. Worth” from the defunct Amon Carter Field/Greater Southwest International Airport, just south of Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport, before the former GSW was redeveloped for commercial real estate (see our B-36 article HERE). As such, TB-58A Hustler 55-0668 remained at Davis-Monthan AFB until the US Air Force came up with an ultimatum: get the airplane out of Davis-Monthan, or it gets scrapped. With little in the way of funds, the Museum of Aviation Group team drove out to the Boneyard, towed the aircraft to a remote corner of the base away from the flightline, and began disassembling the supersonic bomber for the return to Fort Worth. In order to reduce the time to get the aircraft back to Fort Worth, the volunteers from the MAG and several engineers from Convair’s parent company, General Dynamics, managed to make an arrangement with the Air Force to have a Lockheed C-5A Galaxy fly the disassembled aircraft to Carswell AFB. The problem with this plan was that the aircraft sections had to fit inside the C-5A’s cargo hold, and being a delta-wing aircraft, the B-58 Hustler did not have a break-point for the wings to be unbolted from the fuselage. This meant that the wing spars had to be severed to allow the wings to come off. In an article written for the journal of the American Aviation Historical Society (AAHS), General Dynamics engineer Rick Matthews recalled the process here: “Since the Hustler has a carry-through wing spar, it had to be severed in order to be taken apart. My job was to take a circular saw fixture assembly and cut through the thick skin and spars along the top and bottom chord of the wings just outside the landing gear box structure. This was done with a grinding wheel blade, five inches at a time… I tried my best to keep the line as straight as possible. It was gut-wrenching to make those cuts — but we knew it was necessary in order to save the bird.” With the aircraft now in pieces, with just three inches of clearance on either side of the C-5A’s cargo hold, 55-0668 was flown back to Carswell Air Force Base. There, Ed Calvert, board member of the Southwest Aerospace Museum, created a system of splice plates and threaded rods to bring the B-58’s wings back together, and the aircraft stood just outside the factory where it had originally been built in 1959 (photo of the aircraft at the Southwest Aerospace Museum in 1985 HERE). By this point, several other aircraft joined it on outdoor display, including B-36J Peacemaker 52-2827 “City of Ft. Worth” and Boeing B-52D Stratofortress 55-0063, but when Carswell Air Force Base became one of many military bases across the United States selected for closure under the Defense Base Closure and Realignment Act of 1990, combined with the transfer of Air Force Plant 4 from General Dynamics to Lockheed Martin, the Southwest Aerospace Museum lost its funding, and was forced to dissolve. Like many aircraft from the museum, TB-58A Hustler 55-0668 had to move out, and in its case, it was towed to nearby Fort Worth Meacham International Airport in 1991. That same year, the Lone Star Flight Museum, then located in Galveston, made an appeal to the National Museum of the USAF to loan TB-58A 55-0668 to them so that they could place it on display. While local aviation enthusiasts from Fort Worth made similar appeals over the aircraft’s roots in Fort Worth, the Lone Star Flight Museum had the facilities that the NMUSAF was looking for, namely an indoor, climate-controlled environment for the aircraft. However, with the 50th anniversary of Air Force Plant 4 coming up, having been originally constructed during WWII to build B-24 Liberator bombers, it was agreed that 55-0668 could stay in Fort Worth long enough for the formal ceremonies to be held at its birthplace at Plant 4. As such, on April 17, 1992, engineers from General Dynamics, the B-58 Hustler Association, and Air Force personnel from Carswell AFB came to Meacham Field, disassembled the wings and tail, towed the aircraft down a closed section of Interstate 820, and had it placed on display for the anniversary celebrations. Following the event, TB-58A 55-0668 was moved to Galveston Airport.

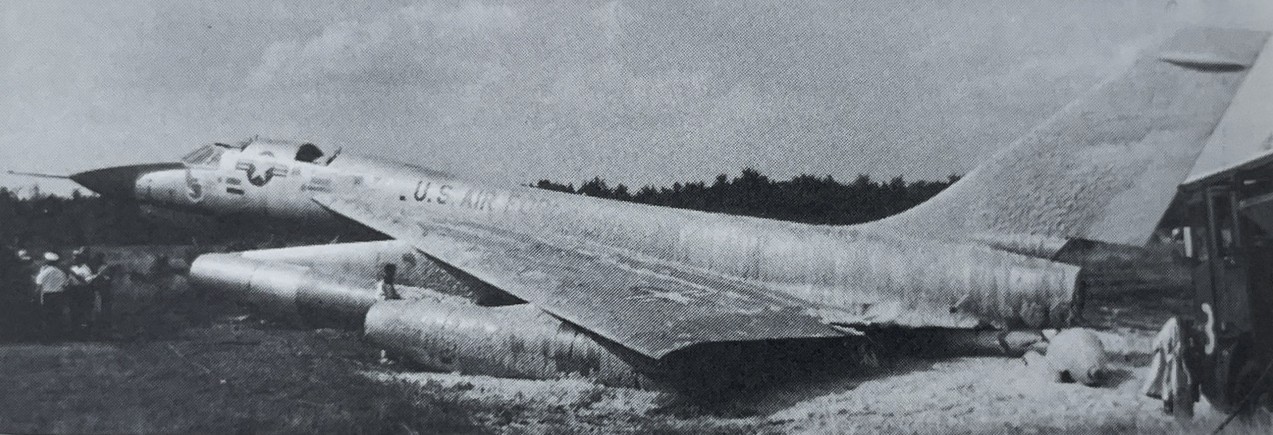

For 16 years, TB-58A Hustler 55-0668 stood proudly on display inside the Lone Star Flight Museum’s hangar at Scholes International Airport at Galveston. The museum received thousands of visitors, and was made the home of the Texas Aviation Hall of Fame. It seemed that TB-58A was at last secure, but that all changed on September 16, 2008, when Hurricane Ike descended upon Galveston. While most of the museum’s airworthy collection, such as the B-17G Thunderbird, were flown to safety, the aircraft on static display and many of the exhibits could not be moved in time before the museum staff had to evacuate, and the hangar was submerged in seven to eight feet of saltwater from the Gulf of Mexico. For TB-58A Hustler 55-0668, the bracing for the severed wing spars was not enough for both the force of the water flooding in, resulting in the splice for the left wing snapping at the mid-section between the Number #1 and #2 engine nacelles, and the outer landing gear bulkhead cracked. The outer section of the left wing, along with the #1 engine nacelle, was found drooping onto the hangar floor.

Despite the best efforts of the museum’s restoration staff, they were forced to focus on repairing other aircraft damaged by Hurricane Ike, and several aircraft would be sold off prior to the museum’s move to their current location at Houston’s Ellington Airport in 2017. In June 2011, though, the Lone Star Flight Museum made the decision to offer the B-58 Hustler 55-0668 back to the National Museum of the USAF. Soon afterwards, the aircraft was offered to Little Rock Air Force Base, where several base commanders had unsuccessfully sought to acquire one of the surviving B-58 Hustlers for display in their Heritage Park. When Colonel Mike Minihan, then commanding officer of Little Rock Air Force Base, received an email from the NMUSAF about the TB-58A in Galveston, Colonel Minihan wrote just two words in reply: “I want!” Soon afterwards, Master Sergeant Eric Bower of the 19th Equipment Maintenance Squadron was sent to Galveston to inspect and evaluate the aircraft. He concluded that a load system to transfer the wing’s weight to the airframe should be arranged, and that a new landing gear support would have to be specially fabricated by the squadron’s maintenance apprentices. On February 8, 2012, the fuselage of TB-58A 55-0668 arrived at Little Rock AFB on the bed of a flatbed trailer driven by Worldwide Aircraft Recovery, which had been the same firm that took the aircraft from Fort Worth to Galveston 20 years earlier. With the rest of the aircraft brought to Little Rock, Worldwide Aircraft’s team got the aircraft standing on its landing gear and its fuel pod reattached, but had to leave for other projects, while base personnel worked on weekends to complete the structural supports for the wings and tail, treat corrosion from Hurricane Ike, and reinstall the radome and pitot tube. Worldwide Aircraft recovery returned to Little Rock in May 2012 to reattach the tail, wings, and engine nacelles with a mobile crane and help from the 19th Equipment Maintenance Squadron, who also treated further corrosion in the wing structure. They also replaced the damaged nose cone of the belly pod with parts from a C-130 external fuel tank, while all open areas on 55-0668, from the engine inlets to the landing gear wells, were covered to prevent birds from nesting inside the aircraft. Finally, on May 3, 2013, Convair TB-58A Hustler 55-0668 was officially dedicated in a formal ceremony at Little Rock AFB’s Heritage Park. During the ceremony, former B-58 pilot Lt. Col. Raymond McLaughlin, USAF (Ret.), was given the honors of christening the display by smashing a bottle of champagne against the nose gear of the Hustler. Today, TB-58A Hustler 55-0668 stands proudly at Little Rock AFB, a fitting tribute to the men who flew and maintained the B-58 at Little Rock, and the dedicated individuals from Fort Worth and Galveston who worked to preserve the aircraft so that it can still be seen and appreciated today.

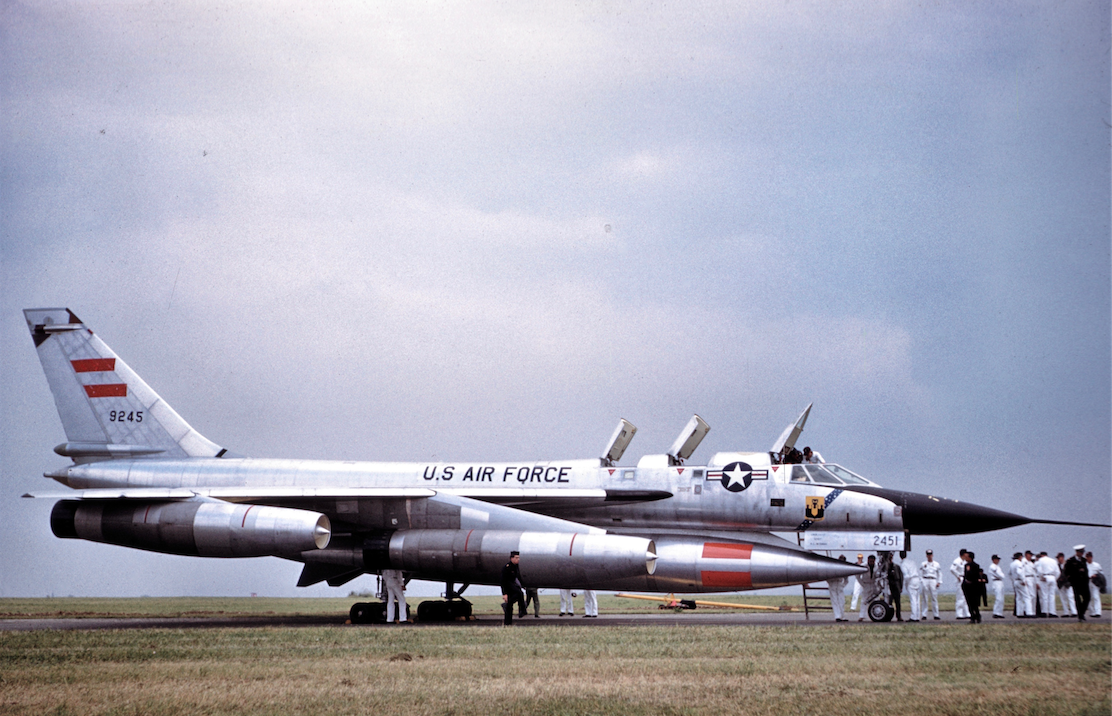

B-58A 59-2437

San Antonio, Texas, has a long history in US military aviation, dating back to when the Aeronautical Division, U.S. Signal Corps, flew Wright and Curtiss biplanes from the grounds of Fort Sam Houston in 1911. It is here on the grounds of the former Kelly Air Force Base that B-58A 59-2437 can be found as a memorial at what is now Port San Antonio. Built at Convair Plant 4 in Fort Worth as construction number 40, 59-2437 was accepted into the USAF’s Strategic Air Command on October 31, 1960, and assigned to the 43rd Bomb Wing at Carswell AFB. After four years of service B-58A 59-2437 accompanied the rest of the 43rd BW to Little Rock AFB, arriving there on August 16, 1964. While in service with the 43rd BW, the aircraft was given the name Firefly II, after B-58A 59-2451 The Firefly, which had earned the coveted Bleriot Trophy, originally set by French aviation pioneer Louis Bleriot in 1930 to be awarded to the first aircrew that could fly for at least a half-hour at an average speed of 2000 km/hr. (1242.74 mph) -2451 set that record with an average speed of 1302.07 mph over a 1073-kilometer closed course on May 10, 1961. 16 days later, The Firefly set two more records on its nonstop flight from Washington, D.C. to attend the Paris Air Show at Le Bourget Airport, setting the Washington, D.C.-to-Paris record at 3 hours, 39 minutes, 48 seconds, and the New York-to-Paris record of 3 hours, 19 minutes, 58 seconds, earning the three-man crew both the Mackay and the Harmon Trophies. Sadly, while being flown by another crew (the same that had so recently earned the Bleriot Trophy), B-58A 59-2451 was destroyed along with its entire crew while attempting low-level aerobatics at Le Bourget before setting off for the United States. As such, B-58A 59-2437 was named Firefly II in memory of Major Elmer Murphy (Pilot), Major Eugene Moses (Navigator/Bombardier), and 1st Lt David Dickerson (Defensive Systems Operator).

Much of 59-2437’s service life was routine, but on July 16, 1968, the aircraft was landing at Little Rock when the right main landing gear collapsed after the gear’s outer cylinder had failed prior to brake-release at takeoff. While the three-man crew consisting of Major George R. Tate, navigator/bombardier Captain Ray G. Walters, and defensive systems operator Captain Francis Mosson all survived without injury, B-58A 59-2437 was deemed to be a write-off. The aircraft was stripped of all useful components to keep the other B-58s at Little Rock operational for the last two years of service before 1970, and the aircraft was relegated to use as a ground trainer. During this time, the aircraft also earned the name Rigley’s Baby but was eventually towed to a remote corner of the base near a grove of trees and occasionally used for firefighter training.

Though Little Rock AFB had established a Heritage Park containing aircraft that had once stationed there, which would later incorporate TB-58A 55-0668, base commanders from the 1970s through the 1980s felt that restoring 59-2437 to static display was not a priority, considering the amount of time and expense in having active-duty personnel restore an airplane that had been previously written-off. However, the commander of Kelly Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas, saw things differently, as B-58s had previously been sent for maintenance at Kelly AFB during their service lives. In 1991, the aircraft was shipped to Kelly Air Force Base, San Antonio, Texas, to be restored and placed on display as a gate guard after sitting at Little Rock AFB for 23 years. On April 15, 1994, a tornado came through San Antonio, and in addition to damaging property at the adjacent Lackland AFB, the San Antonio Express-News reported that B-58A 59-2437 was flipped onto its back during the storm. However, the Hustler was later righted back on its landing gear and repaired. Less than ten years later, though, it was decided to decommission Kelly Air Force Base, with the runways being incorporated into Lackland Air Force Base (now part of Joint Base San Antonio), and the base was officially decommissioned in 2001. However, the city of San Antonio reestablished the site as Port San Antonio, becoming one of the biggest business and industrial parks in South Texas. Even today, B-58A 59-2437 sits on display next to an office building for the management consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton Holding Corporation, while a General Dynamics FB-111A Aardvark, serial number 68-0275, sits on a pedestal on the opposite end of the building. B-58A 59-2437 would also memorialize three members of a B-58 flight crew, retired Brigadier General Hal Confer (a former B-58 pilot), retired Lt. Col Richard H. Weir (navigator/bombardier) and retired Lt. Col. Howard S. Bialas (defensive systems operator), who on January 14, 1961, flew another B-58A, 59-2441 Roadrunner, to a speed record of 1,284.73 miles per hour (2,067.58 kilometers per hour) over a 1,000 kilometer closed circuit above Edwards Air Force Base, earning the Thompson Trophy and setting three records with the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Today, B-58A 59-2437 stands as a monument to the men and women assigned to Kelly Air Force Base and to those who built, crewed, and serviced the B-58 Hustler during its operational career.

B-58A 59-2458

For over 100 years, the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio has been one of the premier aviation museums in the world, and is home to many of the most significant aircraft in the history of American military aviation, from the Wright Brothers to the Lockheed-Martin F-22 Raptor. Many of the most popular aircraft can be found inside the museum’s Eugene W. Kettering Cold War Gallery, including the most well-preserved Convair B-58 Hustler in existence. Built as construction number 61, B-58A 59-2458 was assigned to the 43rd Bomb Wing at Carswell AFB, Fort Worth, Texas. Given Fort Worth’s history with the cattle trade of the Old West period and the Texas Longhorn, the aircraft built and stationed in Fort Worth was given the name Cowtown Hustler. On March 5, 1962, Cowtown Hustler, callsign Tall Man Five-Five, and another B-58A, callsign Tall Man Five Six, would partake in a record-setting flight to break the nonstop speed record from Los Angeles to New York and back again. Inside B-58A 59-2458 Cowtown Hustler were aircraft commander Captain Robert G. Sowers, navigator/bombardier Captain Robert MacDonald, and defensive systems operator First Lieutenant John T. Walton, all from the 65th Bombardment Squadron of the 43rd Bombardment Wing. After four months of training prior to the flight, the two B-58s took off from Carswell AFB, Texas at sunrise, flying at Mach 2 towards Los Angeles. Upon reaching the airspace above Los Angeles, they flew out over the Pacific Ocean to be refueled midair by a Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker. This would be enough fuel for them to fly nonstop to Kansas, where they were to be refueled by another KC-135 before flying through a radar gate to officially start the speed run to New York.

While the B-58 Hustler was one of the fastest aircraft in the USAF, the construction of its aluminum honeycomb skin panels meant that in order to prevent delamination, which would occur at temperatures above 115 °C (239 °F) due to atmospheric friction, the B-58’s top speed could not exceed speeds which could cause excessive heat on the panels. However, prior to the flight, Convair engineers had installed heat sensors in the honeycomb skin panels of both B-58s, and cleared the two aircraft to achieve a maximum temperature of 125 °C (257 °F), allowing these two B-58 Hustlers to exceed 1,400 miles per hour (2,253 kilometers per hour). This led to the flight receiving the codename Operation Heat Rise. After refueling off the California coast, radar initially failed to pick up the two Hustlers against the clutter of ground-based radar signals, causing the two B-58s to return to the KC-135 to top off their fuel, then turn around for visual confirmation that they had entered the radar gate. Throughout the flight, both B-58s were cleared to fly at Flight Level 250 and 500 (between 25,000 to 50,000 feet), and the FAA had cleared all air traffic at those altitudes to ensure safe passage for the record-setting B-58s, and the two aircraft flew at 50,000 feet at Mach 2 on the stretch from Los Angeles to Kansas. When it came time to refuel once again, both Cowtown Hustler and Tall Man Five-Six descended to 25,000 feet and lowered their airspeed to refuel with the KC-135, taking 21 minutes to take on 8,500 gallons (321,760 liters) of fuel before climbing back up to 45,000 feet and returning to Mach 2 for the run to New York.

At 2 hours, 58.71 seconds, B-58A 59-2458 Cowtown Hustler crossed the radar gate at New York with an average speed of 1,214.65 miles per hour (1,954.79 kilometers per hour). B-58A Tall Man Five-Six followed just one minute behind. Soon after flying over New York, the B-58 Hustlers made a fourth aerial refueling, this time over the Atlantic Ocean, but Tall Man Five-Six began to develop mechanical troubles and was forced to disengage from the flight back to Los Angeles, leaving just Cowtown Hustler to complete the mission. Speeding back across the North American continent, Cowtown Hustler made its fifth aerial refueling over Kansas before landing in Los Angeles to celebrate the end of its record-breaking flight. The Cowtown Hustler had flown from New York to Los Angeles in 2 hours, 15 minutes, 50.08 seconds at an average speed of 1,081.81 miles per hour (1,741.00 kilometers per hour). Total time elapsed for the complete Los Angeles-New York-Los Angeles flight was 4 hours, 41 minutes, 14.98 seconds, and the results were certified by the National Aeronautic Association (NAA), working on behalf of the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). For this achievement, DSO 1st Lt. John T. Walton was promoted to Captain, and all three of the crew, Captains Sowers, MacDonald, and Walton were each awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for their flight, and later that year, the crew was awarded both the Bendix and the Mackay Trophies, with this flight representing the last time the original Bendix Trophy was awarded. The flight was also remarkable in that it was the first time that an aircraft had flown across the transcontinental United States faster than the Earth’s rotation.

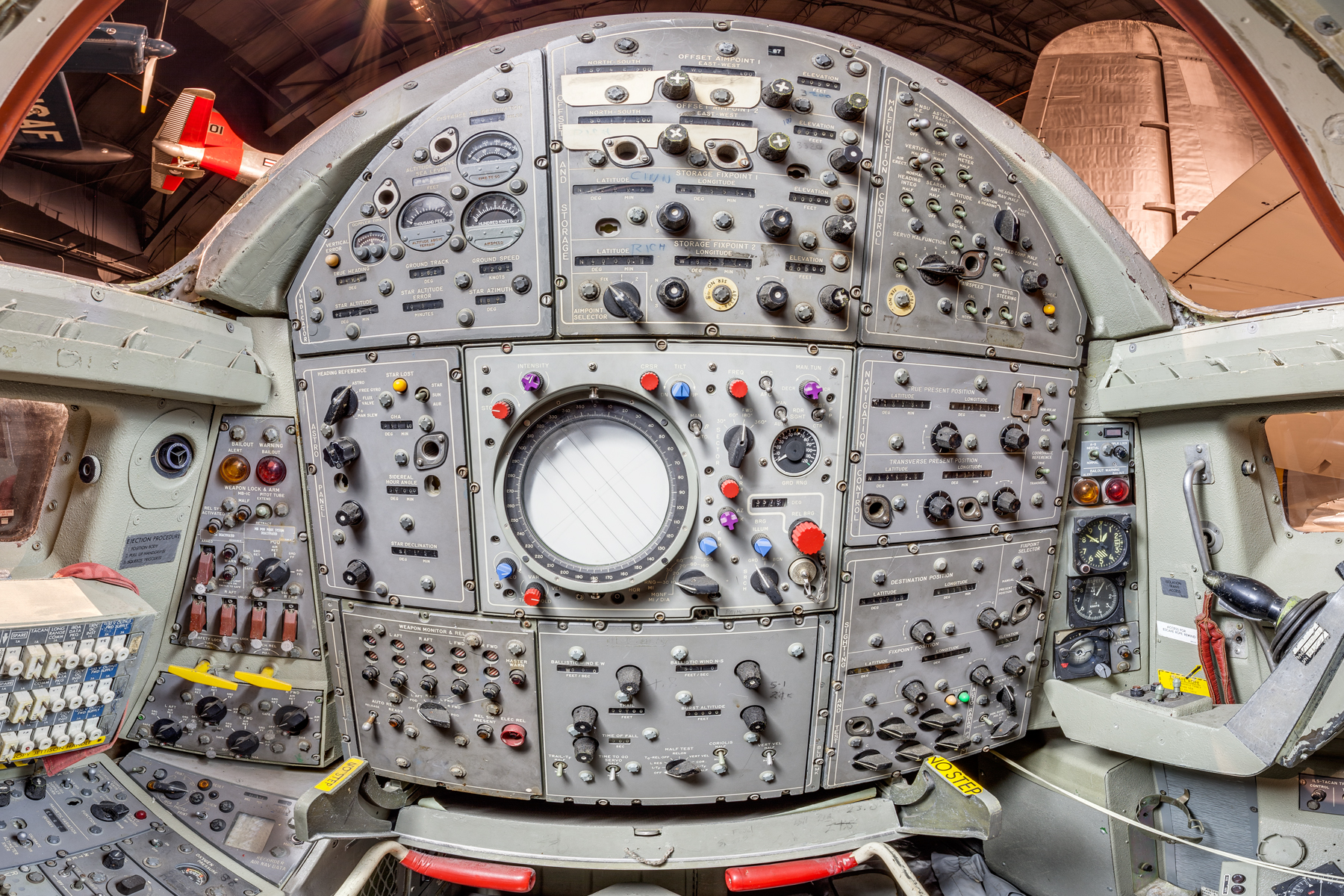

After this remarkable flight, B-58A 59-2458 returned to routine operations with the 43rd Bombardment Wing and followed the wing in its September 1964 transfer from Carswell AFB to Little Rock Air Force Base, just outside of Jacksonville, Arkansas. As the B-58 Hustler fleet began to be phased out of service, B-58A 59-2458 Cowtown Hustler was transferred to the 2750th Air Base Wing, Air Force Logistics Command, at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio, and made its final flight on December 1, 1969, and was earmarked for permanent display inside the United States Air Force Museum. For over a year, it was kept in outdoor storage on the Wright Field portion of Wright-Patterson AFB in anticipation of the transfer of the USAF Museum from the Patterson Field side to the Wright Field side of the base, where it is currently located. After being displayed in the outdoor Air Park of the new USAF Museum, it was restored during the 1980s, and today the highly-polished aircraft stands proudly alongside dozens of other aircraft inside the museum’s Cold War Gallery, along with a replica of the Bendix Trophy, and commemorative decals applied by the Air Force as a result of its participation in Operation Heat Rise. With the restoration of its three tandem cockpits, Cowtown Hustler also stands as one of, if not the most well-preserved Convair B-58 Hustler still in existence.

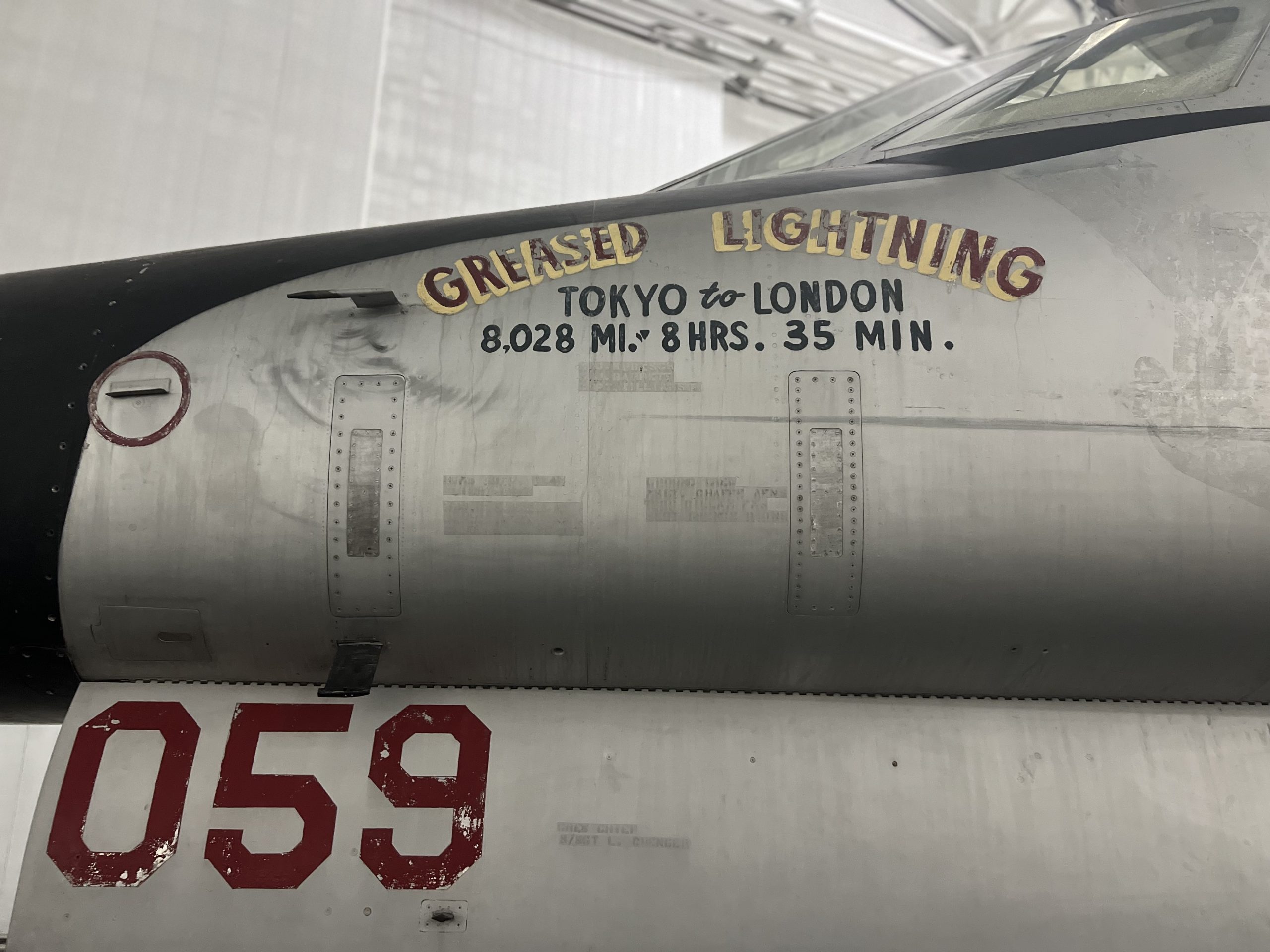

B-58A 61-2059

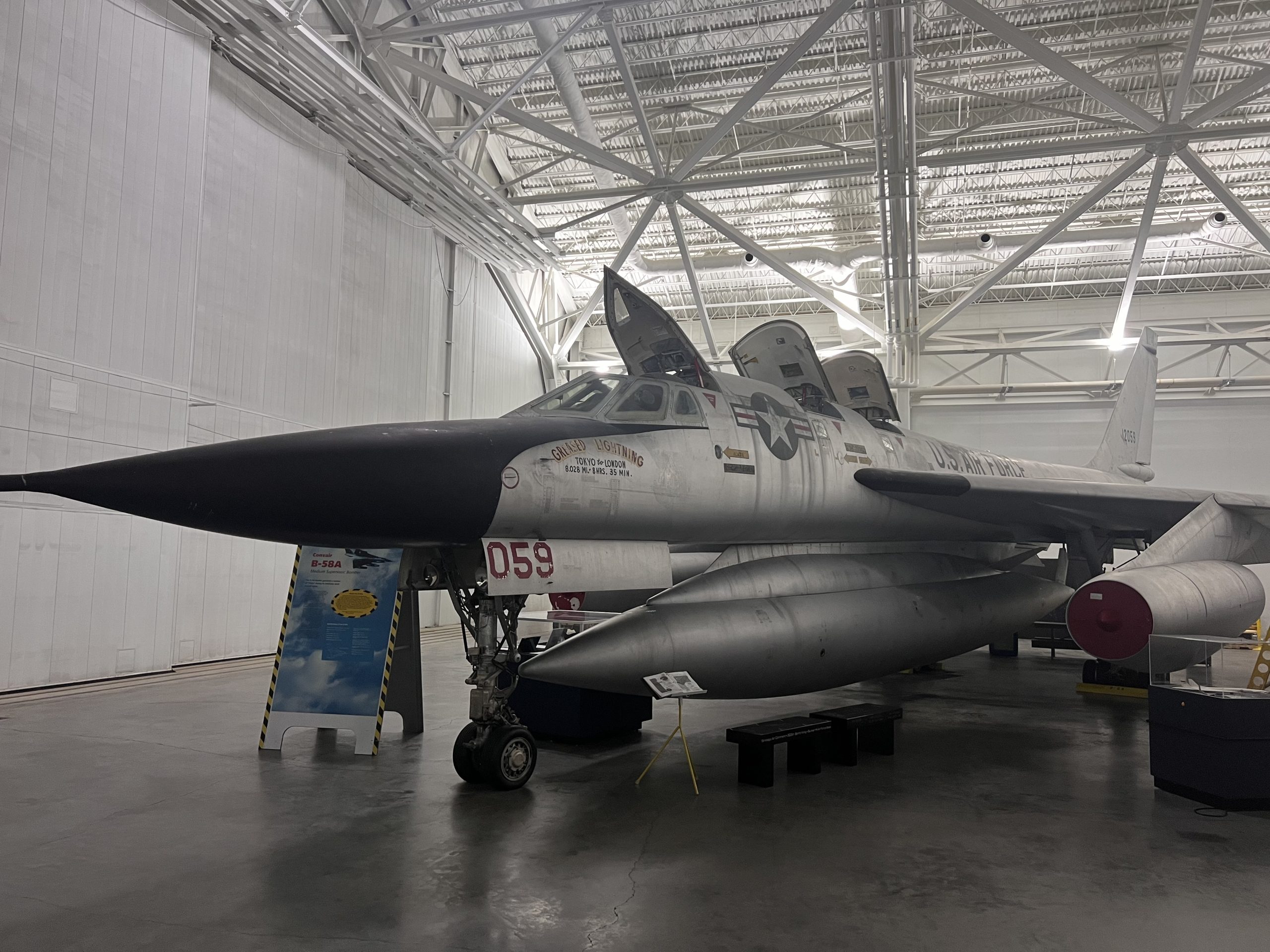

Among the numerous flight records set by the Convair B-58 Hustler over the course of its short ten year operational service life with the USAF, perhaps none is more remarkable than that made by the B-58 Hustler that was named Greased Lightning, which set the nonstop speed record from Tokyo to London. This particular Hustler can be found on display at the Strategic Air Command and Aerospace Museum of Ashland, Nebraska. Built in Convair’s Plant 4 as construction number 95, B-58A 61-2059 was accepted by the USAF on February 16, 1962, being assigned to the 305th Bombardment Wing at Bunker Hill (later Grissom) AFB, Indiana. During the initial phase of its service with the 305th, 61-2059 was given the name Can Do, which was also the motto of the 305th Bomb Wing. It would be in the summer of 1963, though, that a flight that would cement 61-2059’s legacy in the history of US military aviation began to take shape. In order to demonstrate the ability of Strategic Air Command (SAC) to respond quickly and effectively to reach targets around the world at speeds once considered impossible, General Thomas S. Power, SAC’s commander in chief, ordered that a nonstop, long-range, and supersonic flight be planned to publicly demonstrate the capabilities of the Convair B-58 Hustler. It would be decided, based on prior operational training with the “Glass Brick” and “Alarm Bell” missions, that the flight would be nonstop from Tokyo to London by way of the Arctic Circle. This would also put the crew within range of KC-135 Stratotankers for aerial refueling. The final plan would be approved under the codename Greased Lightning.

On October 9, 1963, B-58A 61-2059 Can Do, along with two other B-58s, departed from Bunker Hill AFB, headed for Tokyo. The three-man flight crew consisted of Major Sidney J. Kubesch (Aircraft Commander), Major John Barrett (Navigator), and Captain Gerard Williamson (Defensive Systems Operator), all codenamed Crew S-12. Flying at subsonic speeds to conserve fuel over the Pacific Ocean, they made their first stop at Anderson AFB, Guam, after flying 14 hours, 10 minutes nonstop from Bunker Hill, then proceeded to Kadena AFB, Okinawa, where they would begin the flight. Similar to the Los Angeles to New York and back flight of 59-2458 Cowtown Hustler, 61-2059 would pass through a radar gate over Tokyo, which would be recorded by officials from the FAI, who would then start their timers to record the total flight time from Tokyo to London. At 12:00 pm on October 16, 1963, B-58A 61-2059 departed from Okinawa to begin its record-setting flight, followed in quick succession by the other two Hustlers. At 1:27 pm local time, the aircraft entered the radar gate over Tokyo, and the FAI officials began timing the aircraft. One hour after leaving Tokyo, the three B-58s made their first aerial refueling off the northern coast of Japan before resuming their supersonic cruise at 50,000 feet. The second aerial refueling was held above the small island of Shemya in the Aleutian Island chain, with the B-58s crossing the International Date Line while enroute to Shemya.

The next phase of the flight would prove to be challenging. While heading for their next refueling rendezvous over Anchorage, Alaska, the weather began to worsen for the KC-135 tankers, and one of the B-58s began suffering issues with its navigation system. While monitoring the live situation from Offutt AFB, Bellevue, Nebraska, SAC headquarters ordered the afflicted B-58 to divert to Eielson AFB, Alaska, while another B-58 was to divert to Chicago, and then back to Bunker Hill, leaving just B-58A 61-2059 and Crew S-12 to complete the flight to London. Over Anchorage, the KC-135 battled through turbulence and was flying in conditions where visibility was reduced to one mile. Aerial refueling is a challenging prospect in clear, smooth skies, let alone in unsteady air with low visibility. The two flight crews on the B-58 and the KC-135, therefore, decided to ascend from 26,000 feet to 28,000, and were now situated above the weather in bright starlight, though there was still enough turbulence to keep all involved attentive. This also made it easier for the official Fédération Aéronautique Internationale observer to visually confirm the presence of 61-2059 for the records. Even after coupling, the turbulence separated the B-58 and the KC-135 on several occasions as the tanker was transferring enough fuel for 61-2059 to fly nonstop to Greenland. After 38 minutes, the KC-135 had transferred enough fuel to 61-2059 to decouple for the last time, and Crew S-12 were on their way to their next refueling rendezvous near Thule Air Base (now Pituffik Space Base), Greenland. Following the refueling there, 61-2059 headed for its final aerial refueling rendezvous, meeting another KC-135 above Iceland for the home stretch to London. Following the final aerial refueling, though, the afterburner on the number three engine failed to light, forcing a reduction in speed to Mach 1.4. With a greater fuel consumption rate at Mach 1.4 than at Mach 2, the crew of 61-2059 was forced to decelerate to subsonic speeds before crossing the Scottish coast. At 3:34 pm local time, B-58A 61-2059 passed through the radar lock above London, then finally landed at RAF Greenham Common, Berkshire, setting a new speed record of 8 hours, 35 minutes, 20.4 seconds. According to the FAI, the flight of Greased Lightning was made with an average speed of 692.71 miles per hour (1,114.81 kilometers per hour), with the time from Tokyo to Anchorage, Alaska being 3 hours, 9 minutes, 42 seconds at an average speed of 1,093.4 miles per hour (1,759.7 kilometers per hour); and the average speed on the Anchorage to London leg being 5 hours, 24 minutes, 54 seconds at 826.9 miles per hour (1.330.8 kilometers per hour). The record of Greased Lightning still stands to this day.

After setting the record, 61-2059 Greased Lightning returned to regular flight duties with the 305th Bomb Wing, where it would remain in service until the end of its career with the USAF. With the retirement of the Convair B-58 Hustler fleet set for January 1970, B-58A 61-2059 was selected in 1969 to be preserved in the Strategic Air Command Museum at SAC’s headquarters at Offutt AFB, Nebraska. However, the aircraft would sit outdoors in the seasonal Nebraska weather for nearly thirty years before the museum and its aircraft were moved from Offutt AFB to a new site just off Interstate 80 near Ashland, with the aircraft being moved by Worldwide Aircraft Recovery of Bellevue, Nebraska, and the museum reopening on May 16, 1998. Since then, B-58A 61-2059 Greased Lightning has been on display inside of the Strategic Air Command and Aerospace Museum’s Hangar A. While the aircraft still has a weathered look from its time outdoors at Offutt, museum restoration volunteers have been hard at work refurbishing other aircraft in the collection that suffered similar exposure. Perhaps in the near future, this record-setting Hustler will be the next big project for the Strategic Air Command and Aerospace Museum, but until then, it remains on public display as yet another reminder of the Cold War capabilities of Strategic Air Command.

B-58A 61-2080

At last, we come to what is quite literally the last Convair B-58 Hustler. Located at the Pima Air and Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona, it is not only the final B-58 that was ever produced, but it also sits adjacent to Davis-Monthan AFB, where a majority of the B-58 fleet was cut up for scrap. Built as construction number 116, B-58A 61-2080 was met with local fanfare by the Convair employees at Fort Worth when it rolled out of Plant 4. After making its first flight on October 23, 1962, the aircraft was formally accepted into the USAF three days later, on October 26. Shortly thereafter, the aircraft was transferred to the 305th Bomb Wing stationed at Bunker Hill (later Grissom) AFB, Indiana. Throughout its service life, B-58A 61-2080 had a comparatively routine service record and would remain as one of the final B-58s kept in operational service with the USAF. With the retirement of the Convair B-58 Hustlers in January 1970, 61-2080 would make its final flight on January 6, 1970, arriving at Davis-Monthan AFB to be placed in outdoor storage at the Military Aircraft Storage and Disposition Center (MASDC)/ “Boneyard”, along with much of the remainder of the B-58 fleet.

Although most of the B-58 Hustlers flown into Davis-Monthan were eventually sold for scrap by 1977, B-58A 61-2080 was spared this fate in the mid 1970s when it became one of around 50 aircraft that represented the Pima County Air Museum (now the Pima Air and Space Museum) when the museum was opened to the public for the first time on May 8, 1976. Since then, B-58A 61-2080 now stands as one of over 400 aircraft on display at what is currently one of the world’s largest non-government funded aviation museums in the entire world, with the aircraft standing between the museum’s Martin B-57E Canberra and Douglas WB-66D Destroyer. With the aircraft being among the majority of the museum’s collection in standing outdoors, aircraft are occasionally pulled from display for refurbishment by the museum, so at some point, the last Convair B-58 Hustler ever built may yet find itself with a fresh coat of paint, but for now, it remains on display in one of the world’s most extensive aircraft collections.

Honorable Mention: B-58 Rocket Sled “Texas Hustler”

Though not strictly a surviving Convair B-58 Hustler, no exhaustive list meant to cover every surviving B-58 would be complete without mentioning the Texas Hustler. When the B-58 Hustler was being developed, one of the primary concerns over the development of the aircraft was how the pilots would escape from the aircraft in the event that it would be shot down in a war or suffer a mechanical malfunction while flying at Mach 2 at high altitudes. While the solution to this were individual escape capsules developed by the Stanley Aviation Company of Denver, Colorado, which were airtight and pressurized for high-altitude flight, had shock absorbers for ground landings, and equipped with inflatable float cells for water landings.

In order to evaluate different solutions to solving the issue of ejecting from the B-58, Convair’s engineers worked with the Coleman Engineering Company of Los Angeles, specializing in the manufacture of rocket sleds, to construct a special nose section of a B-58 Hustler that would be part of a rocket sled which would be accelerated at supersonic speeds on a set of ground rails. The B-58 rocket sled was then transported to the Hurricane Supersonic Research Site (HSRS) on the top of Hurricane Mesa, Utah, located between the city of St. George and Zion National Park. There, engineers from Stanley Aviation fitted the escape capsules into the rocket sled, which was often nicknamed the Texas Hustler, with the track being situated close enough to the side of the mesa for the parachutes on the escape capsules to be tested, and for the capsules to be recovered and analyzed for any test data that could be obtained. Some of this testing with the B-58 rocket sled was later shown in the documentary Escape and Survive (link to that documentary HERE).

With the escape capsules being proven to be practical, the B-58 rocket sled was used for further tests with other ejection seats at Holloman AFB, New Mexico, and even saw further use after the B-58s were retired from active service in 1970. Eventually, though, the Texas Hustler would outlive its usefulness, but was purchased from a scrap dealer in Alamogordo, New Mexico and placed on outdoor display at the 8th Air Force Museum (now the Barksdale Global Power Museum) at Barksdale AFB, near Shreveport, Louisiana, with the rocket sled officially on long-term loan from the National Museum of the USAF. For over 30 years, the B-58 rocket sled remained on display at Barksdale, but because of the fact that the museum is inside the boundaries of Barksdale AFB, the number of visitors has been limited due to the forms required to be authorized to get on base property.

In March 2018, the B-58 rocket sled made one final move across the country when it was trucked from the Barksdale Global Power Museum to the Grissom Air Museum at Grissom Air Reserve Base, Indiana, already home to TB-58A 55-0663, and was especially fitting considering Grissom’s history as one of only three bases to host a B-58 bomber wing. Now, the B-58 rocket sled is more publicly accessible, and the Grissom Air Museum is the only place where one can see both a real Convair B-58 Hustler and the B-58 rocket sled at the same place.

In the end, the Convair B-58 Hustler may not have had the longest career of a USAF bomber, but its legacy endures in the eight surviving examples found across the United States today, and many of its speed records set during the 1960s remain unchallenged to this day. Numerous B-58 aircrews would, in fact, also join the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird program, as they were some of the USAF’s most experienced crews in flying at Mach 2 continuously for long duration and long-distance flights. The B-58 also set a precedent for more capable aircraft that came to replace it, and to this day, it is still a favorite of aviation history enthusiasts around the world. If you have the opportunity to see even one of these rare Cold War bombers, the B-58 Hustler retains an aura of being fast while standing still. Be sure to see them if you can.

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.