In the early 1960s, when strategic aviation still believed that speed could outrun missiles, the Soviet Union began work on an aircraft that seemed to belong more to the future than to its own time. The project was known as “Project 100,” later called the Sukhoi T-4, and it emerged from a 1961 requirement for a long-range strike and reconnaissance aircraft capable of searching for and destroying small, mobile, and fixed targets at sea and on land, with a flight range of roughly 7,000 kilometers (4,350 miles). A competition followed between the design bureaus of Sukhoi, Tupolev, and Yakovlev, and Sukhoi’s proposal won. Its promise was not subtle. The aircraft was designed to cruise at approximately Mach 3 at a speed that, in theory, would make interception by contemporary air defenses extremely difficult. The government formally authorized development in December 1963, and the program was placed under Deputy Chief Designer Nikolai Chernyakov.

Designing the Sukhoi T-4 for Mach 3

By the middle of 1964, the design had been approved, but approval did not mean the hard part was over. The T-4 was not simply a cleaner or faster version of an earlier bomber; it was a different kind of machine altogether. It had no traditional tailplane, its broad double-delta wing swept sharply back, and small foreplanes were added near the nose to fine-tune its balance at very high speed. The designers intentionally reduced its natural stability, because at Mach 3, too much stability could make an aircraft unresponsive. In addition, at those speeds, an aircraft’s skin temperatures could rise above 220 to 330 degrees Celsius (428 to 626 degrees Fahrenheit). So, aluminum was no longer sufficient, and the airframe would be built from titanium and high-strength steel, forcing Soviet industry to develop new production techniques almost from scratch. It required new welding methods, new machining processes, and new ways to shape and join metal that resisted both stress and heat. Entire research teams were formed just to understand how titanium behaved under load, how coatings reacted to temperature cycles, and how full-scale sections of structure would survive prolonged exposure to extreme conditions. Thus, the T-4 was not only an aircraft project; it was an industrial leap, built piece by piece before it could ever leave the ground.

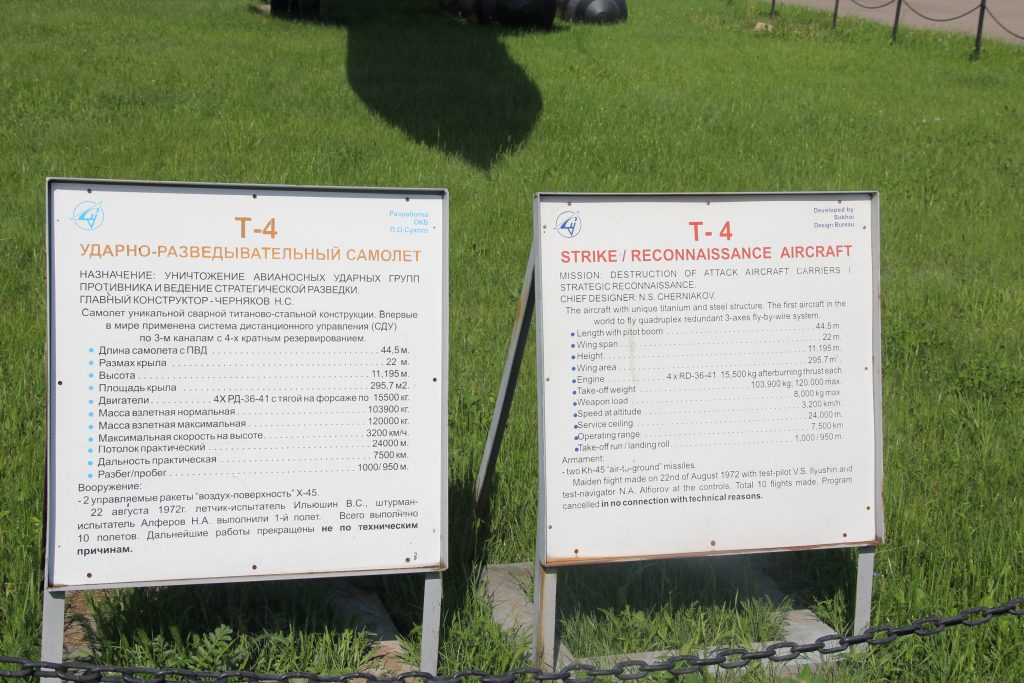

The propulsion system required a similar ambition. The final configuration placed four engines in a “bath” arrangement beneath the fuselage, fed by the Soviet Union’s first supersonic mixed-compression variable-geometry intake designed for automatic start at Mach 3. To power the aircraft, the Kolesov design bureau developed the RD-36-41 turbojet, capable of sustaining high-temperature, high-speed cruise. Even here, nearly every component required new solutions. Inside, the T-4 introduced features uncommon in Soviet practice at the time, such as a quadruple-redundant fly-by-wire control system, an autothrottle, high-pressure hydraulics operating at 3,982.5 pounds per square inch (PSI), turbine-driven fuel pumps, and a liquid-nitrogen-based inerting system. By the time design matured, more than 200 inventions had been formally registered by Sukhoi engineers, and if subassemblies were counted, the number approached 600. No previous Soviet aircraft had required such a concentration of new intellectual property. The aircraft was not only ambitious from the outside, but inside as well. The avionics suite was intended to carry the NK-4 navigation complex and the Okean integrated system, combining fire-control, reconnaissance, defensive countermeasures, and communications into a unified architecture. Its primary weapon was to be three Kh-45 aeroballistic missiles, each with an estimated range of 550 to 600 kilometers (342 to 373 miles) and cruise speeds between Mach 5 and 7. The concept was to allow the T-4 to approach at extreme speed and altitude, launch long-range missiles, and withdraw before effective interception could occur.

Initial Testing and Cancellation

Between 1966 and 1974, four airframes were assembled at the Tushino Machine-Building Plant, one for static testing and three intended for flight. The first flying prototype, Article 101, was completed in late 1971 and transferred to the Flight Research Institute at Zhukovsky. On 22 August 1972, test pilot Vladimir Ilyushin and navigator Nikolai Alfyorov lifted the aircraft into the air for the first time. Over the next year and a half, ten flights were completed. Powered by four Kolesov RD-36-41 afterburning turbojets, each producing 35,000 pounds of thrust, the aircraft was designed for speeds up to 2,000 miles per hour with a projected service ceiling between 66,000 and 79,000 feet. However, in flight testing, the T-4 only achieved Mach 1.3 at 39,370 feet, which was well below its intended Mach 3 envelope. But it was sufficient to validate basic systems and structural integrity, and even in limited testing, it demonstrated that the design was viable. Yet the environment around the T-4 was shifting. By the early 1970s, surface-to-air missile systems had grown increasingly capable. The assumption that speed and altitude could guarantee survivability was less certain. At the same time, the T-4’s reliance on large quantities of titanium and specialized manufacturing processes made it exceptionally expensive. It had already acquired a reputation inside the industry as a demanding and costly undertaking.

In addition, more versatile and economically sustainable aircraft were favored, and competing projects offered broader operational flexibility at lower cost. The infrastructure required to produce the T-4 in meaningful numbers, as initially planned, would have required a substantial reallocation of industrial resources. In 1974, work was suspended, and in December 1975, the program was officially terminated. Only four airframes had been completed, and none entered operational service. However, the T-4 had an impact on the Soviet aviation dictionary. Sukhoi used it as a basis for later conceptual developments, including variable-sweep derivatives and the T-4MS, which competed in a strategic bomber program in the early 1970s. Many structural techniques, high-temperature material processes, and systems concepts developed for the T-4 informed later Soviet high-performance aircraft. In technical terms, the aircraft had proven that a sustained Mach 3 cruise was theoretically achievable within Soviet industrial capability. In strategic terms, it revealed that speed alone could no longer guarantee relevance. Like many other aircraft in the Grounded Dreams series, the Sukhoi T-4 never stood alert on a runway, never carried operational missiles, and never reached its design speed, but it represented a belief that titanium, mathematics, and engineering discipline could extend the logic of supersonic flight into a new realm. Check out more Grounded Dreams articles HERE.