In the years after World War II, the United States started reorganizing its military around nuclear weapons, with the US Air Force turning the Strategic Air Command into a force of long-range bombers. The US Navy leaders also realized that the future of military budgets and influence would depend heavily on who controlled the nation’s nuclear strike capability. With defense spending tightening and the Air Force positioning itself as the main nuclear arm, the Navy began searching for a way to maintain its role in strategic deterrence. The Navy’s first idea was to build a massive “super carrier” called USS United States that would operate large strategic bombers at sea. But that plan was canceled in 1949 due to intense post-WWII defense budget cuts and severe interservice rivalry, forcing naval planners to think differently. What followed was one of the most unusual concepts of the Cold War era, which the world today knows as the P6M SeaMaster.

Birth of the P6M SeaMaster

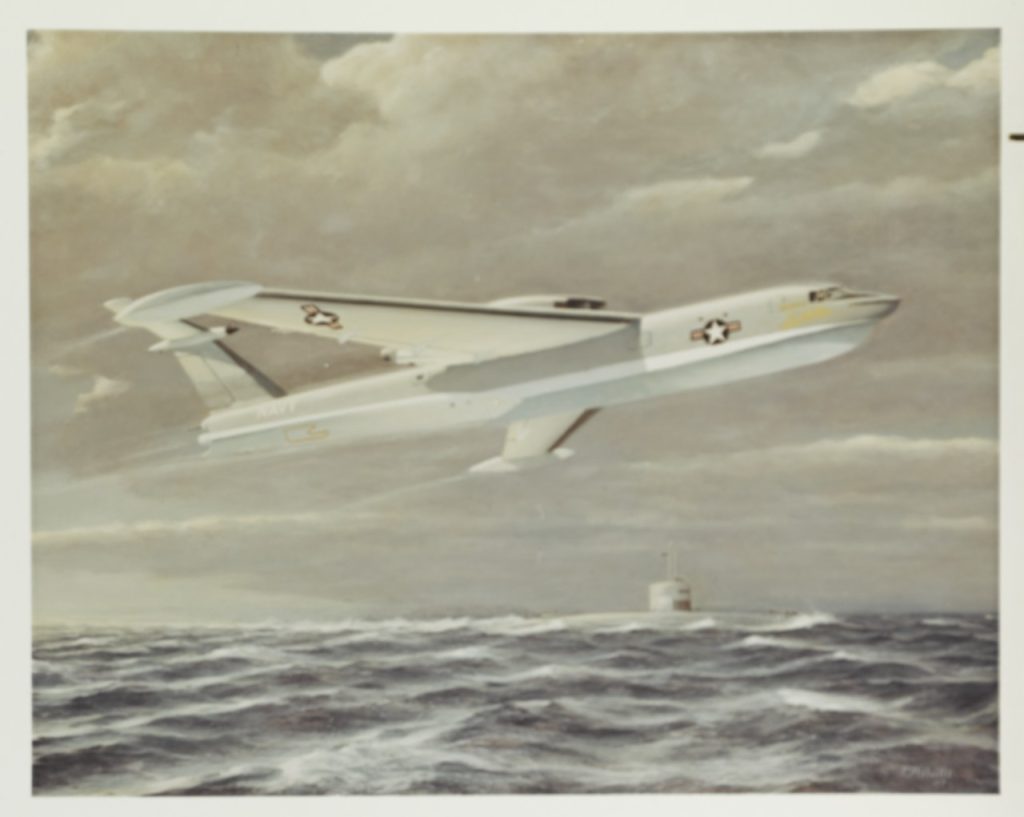

The Navy wanted a force of jet-powered seaplanes, calling it the Seaplane Striking Force (SSF), that could operate far from fixed bases, launch nuclear strikes, and disappear back into the ocean. Under this concept, large flying boats could operate from remote ocean areas, supported by seaplane tenders or even submarines, while also performing conventional bombing, reconnaissance, and mine-laying missions, the last of which was considered especially important given the narrow sea routes the Soviet Navy would have to pass through in any major conflict. In 1951, the Navy formally asked industry to design such an aircraft, one capable of carrying 30,000 pounds of load over 1,500 miles at Mach 0.9 while flying at low altitude to evade defenses.

Martin won the competition, and the aircraft that emerged became the P6M SeaMaster, a sleek, jet-powered flying boat that looked more like a bomber than a traditional seaplane. Following the P5M Marlin as a starting point, Martin’s SeaMaster combined a carefully shaped hull with swept wings, wingtip floats, and four Allison J71-A-4 turbojet engines with 57.87 kN afterburning thrust mounted high above the waterline to reduce spray ingestion during takeoff. From the beginning, the SeaMaster was a technically demanding machine, designed to fly fast at low altitude, carry nuclear or conventional weapons internally, and operate far from established bases, all while taking off and landing on open water. It borrowed heavily from Martin’s experimental bomber work, using advanced control surfaces, a rotating bomb bay that could stay sealed against water, and a tail turret for self-defense, while housing a four-person crew in a pressurized cockpit.

The Tests

The first SeaMaster prototype, designated YP6M-1, flew for the first time in July 1955, and the aircraft’s performance showed promise, particularly in speed and low-level flight. However, the flight test revealed a serious flaw as the engines’ exhaust was scorching the rear fuselage, forcing limits on afterburner use. It would make handling such a complex aircraft difficult. Still, the Navy publicly announced the SeaMaster in November 1955, and a second XP6M-1 prototype was rolled out. The program suffered multiple setbacks when both prototypes were lost in separate accidents, one due to a control system failure that caused the aircraft to pitch downward, and the other due to a miscalculation in tail control design. Despite these losses, the Navy committed to supporting infrastructure and pushing the program forward with pre-production aircraft.

After losing both early prototypes, Martin moved ahead with a revised pre-production version of the SeaMaster, rolling out the YP6M-1 in November 1957 and returning to flight testing a few months later, in January 1958. This updated aircraft was fitted with improved Allison J71-A-6 afterburning engines, which were angled to reduce the blast hitting the rear fuselage, and the engine inlets were moved farther back on the wing to help keep water spray out during takeoff and landing. Five more YP6M-1 aircraft were completed in 1958, and together they took part in a wide-ranging test program that included practice drops of conventional weapons and dummy nuclear payloads, along with trials of reconnaissance equipment during both daytime and night operations.

P6M-2 SeaMaster

The first production version of the SeaMaster, known as the P6M-2, rolled out in early 1959. It was powered by more powerful non-afterburning Pratt & Whitney J75-P-2 turbojet engines producing 77.89 kN thrust, which allowed the aircraft to carry more weight. The engine layout was also cleaned up, with the exhausts now aligned rather than staggered, and the heavier aircraft sat lower in the water, which led designers to remove the wing’s downward angle. Inside, the P6M-2 received a redesigned canopy that improved visibility, along with modern navigation and bombing systems and a mid-air refueling probe. Martin even developed a simple tanker kit that could be installed in the bomb bay, allowing the SeaMaster to quickly switch roles and refuel other aircraft if needed.

By the summer of 1959, three production P6M-2 SeaMasters had been completed, and Navy crews were already training with them in preparation for bringing the aircraft into service the following year, while five more were still under construction. At the same time, however, the Navy kept quietly cutting back its plans, reducing the total order from 24 aircraft to 18, then to just eight, before finally canceling the SeaMaster program altogether on August 21, 1959.

A Solution That was No Longer Needed

When the SeaMaster, with a program cost of about $400 million USD, was finally coming together technically, the strategic world around it was changing even faster. Ballistic missile submarines armed with nuclear missiles were emerging as a far more survivable and effective nuclear deterrent, able to remain hidden for months and strike without warning. Compared to these ballistic missile submarines, a large jet seaplane, no matter how advanced, suddenly looked vulnerable and unnecessary.

By the time it was ready, the SeaMaster was trying to solve a problem the Navy no longer had, pushed aside not by a single flaw but by faster changes in technology and strategy. It was neither a gimmick nor a mistake, but a product of a short, uncertain moment when the Navy was searching for its place in the nuclear age and was willing to take big risks to find it. Like many aircraft in Grounded Dreams, it showed what could be done, and just how quickly even bold ideas can be left behind when priorities change. Check our previous entries HERE.

Related Articles

Kapil is a journalist with nearly a decade of experience. Reported across a wide range of beats with a particular focus on air warfare and military affairs, his work is shaped by a deep interest in twentieth‑century conflict, from both World Wars through the Cold War and Vietnam, as well as the ways these histories inform contemporary security and technology.