In the late 1920s, when most passenger aircraft were so loud that they resembled noisy buses with wings and no hint of luxury, the German aviation company Junkers rolled out an airplane that seemed to belong to another era entirely. A giant all-metal machine that treated flight not as endurance but as an experience, and for a brief moment, the aircraft made the future of air travel look grand. That aircraft was the Junkers G.38, and when it first lifted off from the factory runway in Dessau in November 1929, it was not just another new airliner. It was the largest landplane in the world, second only to the even larger Dornier Do X flying boat, and unlike anything passengers had ever seen.

The idea behind G.38 went back much further than its maiden flight, to German engineer Hugo Junkers’ early belief. He believed that airplanes should not simply hang passengers below thin wings, but carry people, engines, and structure inside a thick, load-bearing wing itself. He had sketched the idea as early as 1910, long before materials, engines, or politics made such ambitions realistic. By the late 1920s, as Germany was slowly pushing past the restrictions of the Versailles Treaty and state funding once again flowed into aviation, Junkers finally had the opportunity to build something close to that vision, and the result was an aircraft that felt part airplane, part “flying salon.”

G.38: A Flying Palace

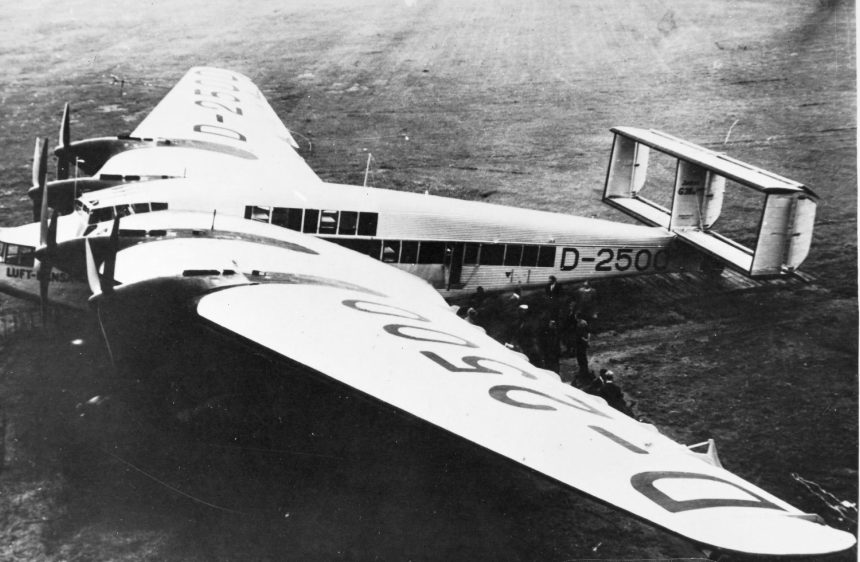

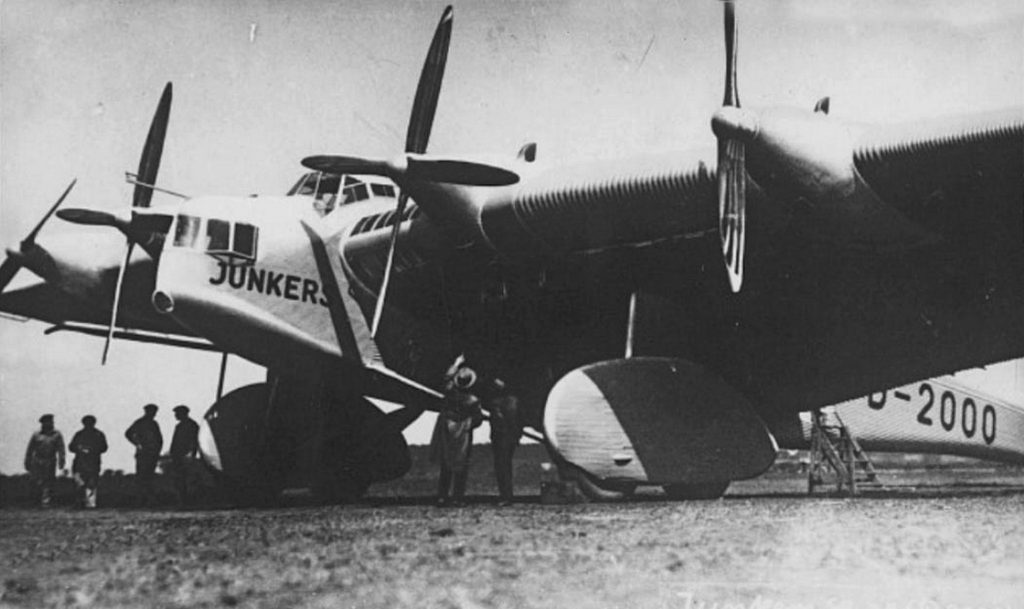

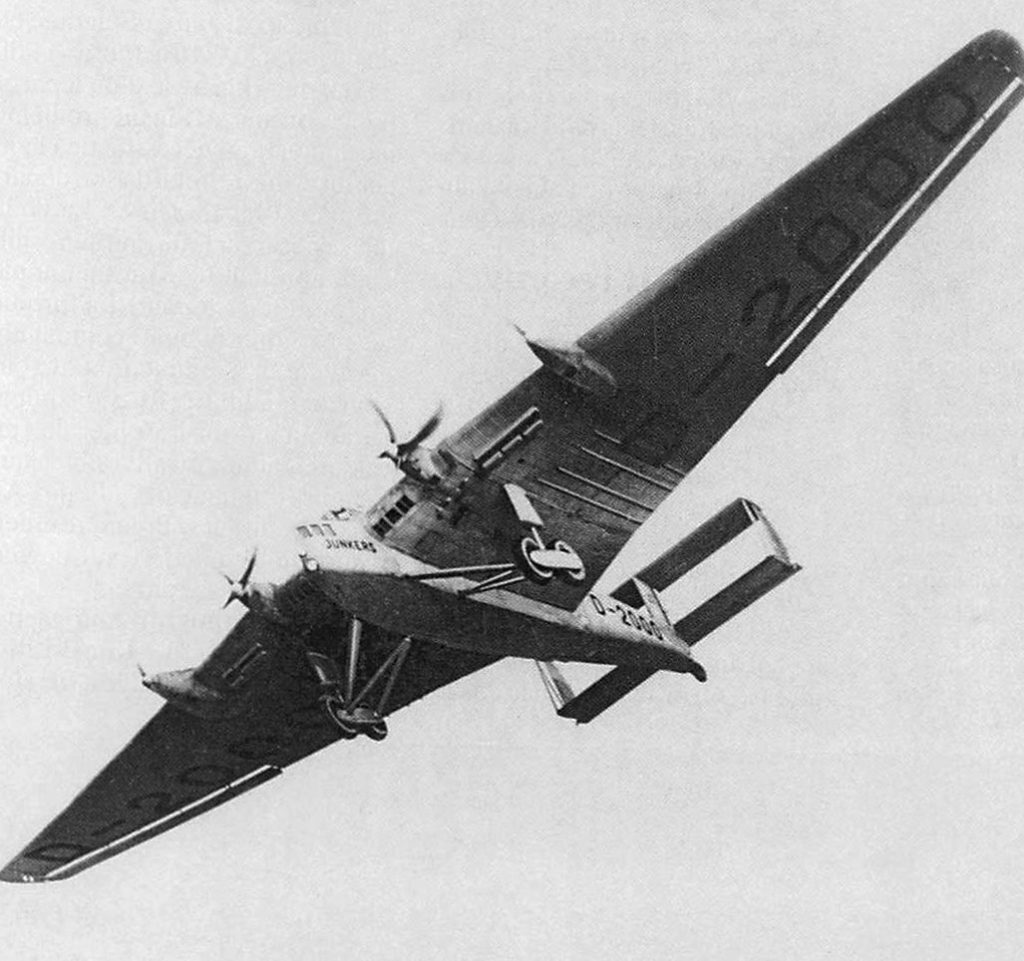

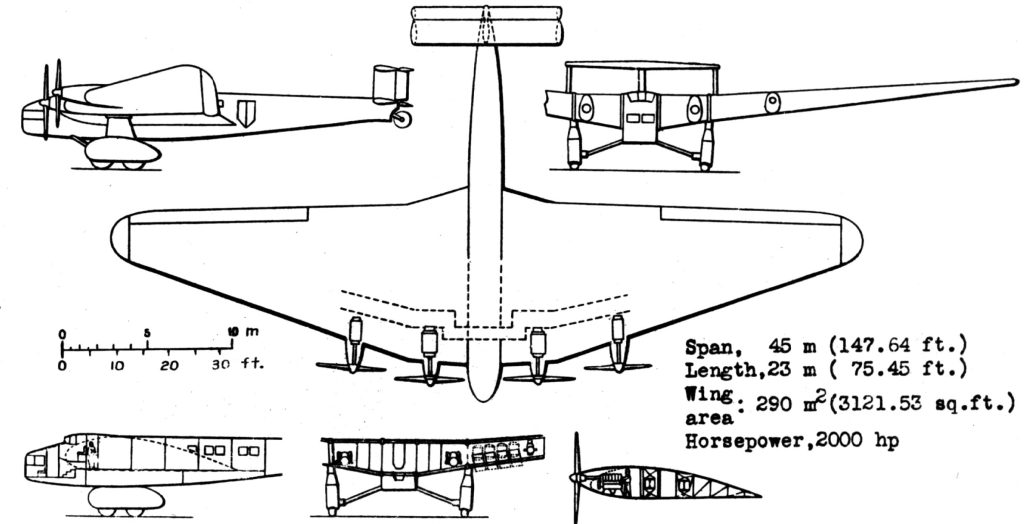

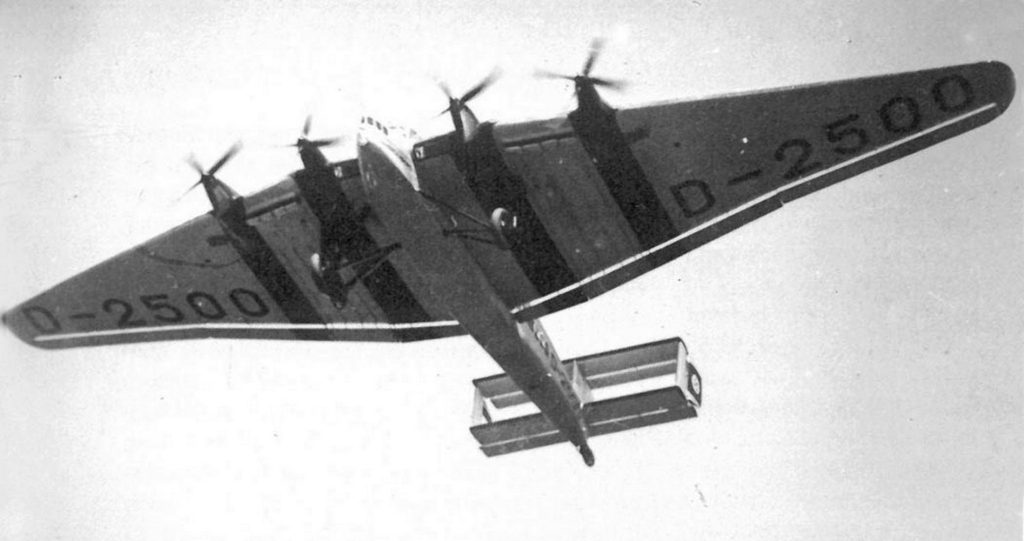

The Junkers G.38 was an all-metal giant, 23.2 meters (76 feet) long with a wingspan of 44 meters (144 feet), wider than many modern narrow-body jets, and weighing over 21,200 kilograms (46,738 pounds) at takeoff. It cruised smoothly at around 200 km/h (124 mph), with a top speed of about 225 km/h (140 mph) and a range of more than 3,400 km (2,112 miles), enough to link major European capitals. Its most distinctive feature was not just its size, but how it used that size, because this was one of the very few aircraft in history in which passengers not only sat in the fuselage, but also inside the wings. From those wing compartments, large curved windows gave riders a clear view straight ahead and down below, creating a flying experience unlike anything before.

Originally designed to carry just 17 passengers, the G.38 provided them with a taste of luxury, with wide upholstered seats, a promenade area, a smoking room, a proper washroom, and service that aimed to rival the luxury of the German passenger-carrying hydrogen-filled rigid airship Graf Zeppelin, which at the time offered unparalleled luxury including silk-covered seats that converted into berths, gourmet meals, and even “luxury cabins.” Four engines were installed inside the wings, an unusual and elegant solution that reduced drag and noise, with only the driveshafts extending outward to the propellers in streamlined housings. The two inner engines produced 600 hp each, while the two outer ones provided 400 hp, all working together to lift the enormous G.38 structure into the air with ease.

A second, longer and heavier G.38 model was also constructed, which featured two decks to accommodate 34 passengers and four identical Junkers L88a engines, each producing 800 hp. Though less luxurious than the first, it was almost two meters longer. Later, as airlines began to focus more on economics, the first aircraft was also upgraded to transport 30 passengers, and the obvious trade was luxury. For a few years, the G.38 became a flying ambassador for German aviation, first appearing at air shows and special events before entering scheduled service with Lufthansa in 1931, flying routes from Berlin to London, Vienna, Amsterdam, and beyond. Technically, it was a success, setting several world records, including speed, endurance, and distance records while carrying heavy payloads, proving that the idea of very large, comfortable landplanes was not only possible, but viable.

An Unexpected Fall

With the Great Depression beginning in 1929, a collapse in travel demand forced airlines to become cautious. Operating large aircraft like the G.38 required labor-intensive maintenance, large crews, and heavy fuel consumption, which added further burdens on airlines. As a result, the aviation world began to favor smaller, simpler aircraft that could turn profits with fewer passengers and lower risks, such as the Junkers Ju 52, which would go on to be built in the thousands.

Also, during a test flight after routine maintenance in May 1936, the first G.38 was damaged in an accident in Dessau. No one was hurt, but the aircraft had to be decommissioned. The second aircraft would never enjoy peaceful passenger service again, as it was taken over by the Nazi regime in 1939 and converted into a military transport, before being destroyed on the ground by British aircraft in Athens in 1941, bringing the short life of the type to a brutal end.

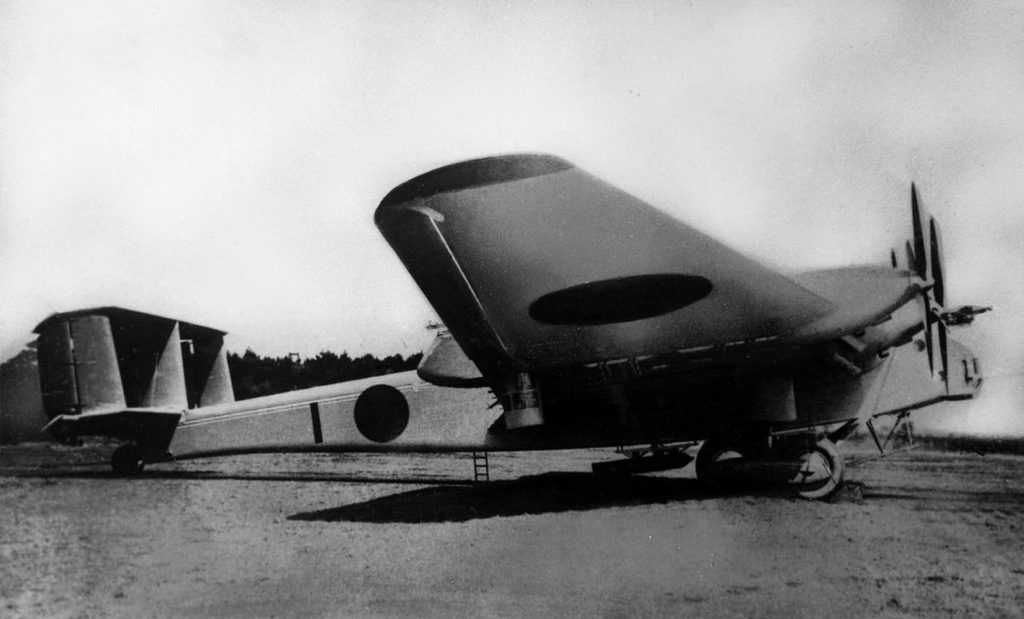

Junkers also designed a military bomber, K.51, based on the G.38, but the German Ministry of Aviation did not accept the design. Later, Japan showed interest in Junkers bomber design, and Mitsubishi built six licensed copies of K.51 as the Ki-20 heavy bomber. However, these bombers saw no combat use due to their rapid obsolescence and excessive secrecy; they were scrapped by 1943. No G.38 was ever built again, not because the aircraft failed, but because the world around it changed faster. It was an airplane designed for luxurious air travel, but aviation history chose efficiency. Like other Grounded Dreams aircraft, the Junkers G.38 was not a poor aircraft, but it was simply too early for a flying palace that showed what the skies might look like. Check our previous entries HERE.