By Randy Malmstrom

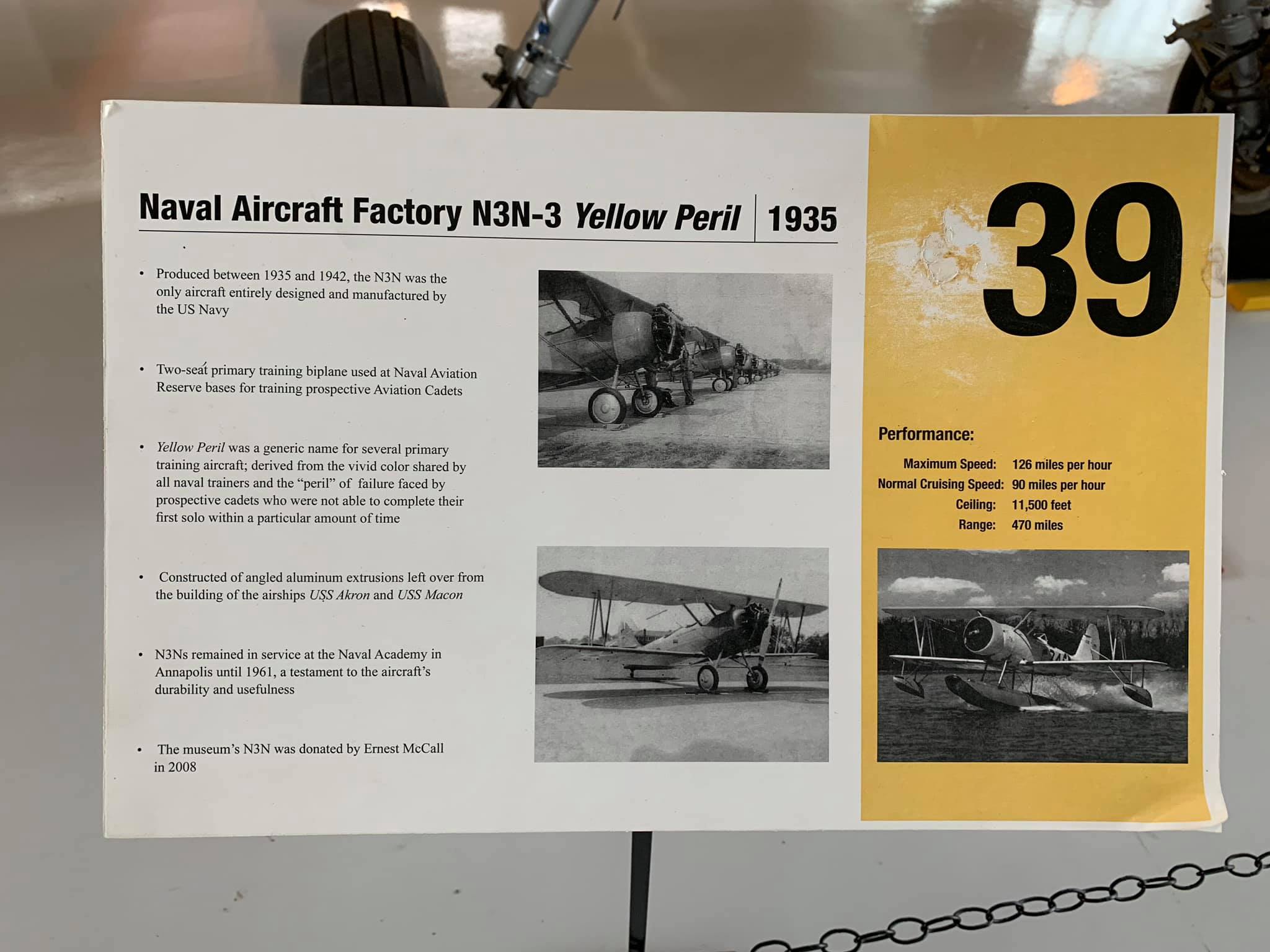

Naval Aircraft Factory N3N-3 Canary (“Yellow Peril”) Bureau Number 2831. A tandem-seat primary trainer, the Canary was known as the “Yellow Peril” and by some accounts was due to its tendency to ground loop (the narrow landing gear stance of only 72 1/2 inches from the centerline of each tire left little in the way of lateral stability at higher touchdown speeds; in addition, taxiing required a series of s-turns due to the limited forward visibility); or by the fact that since 1917, U.S. Navy primary trainers were painted chrome yellow for maximum visibility (whereas the U.S. Army painted their primary trainer fuselages blue and the wings and tail surfaces chrome yellow); or simply the fact that pilots found training harrowing (and if the cadet failed to solo in the prescribed time, was in peril of not becoming an aviator).

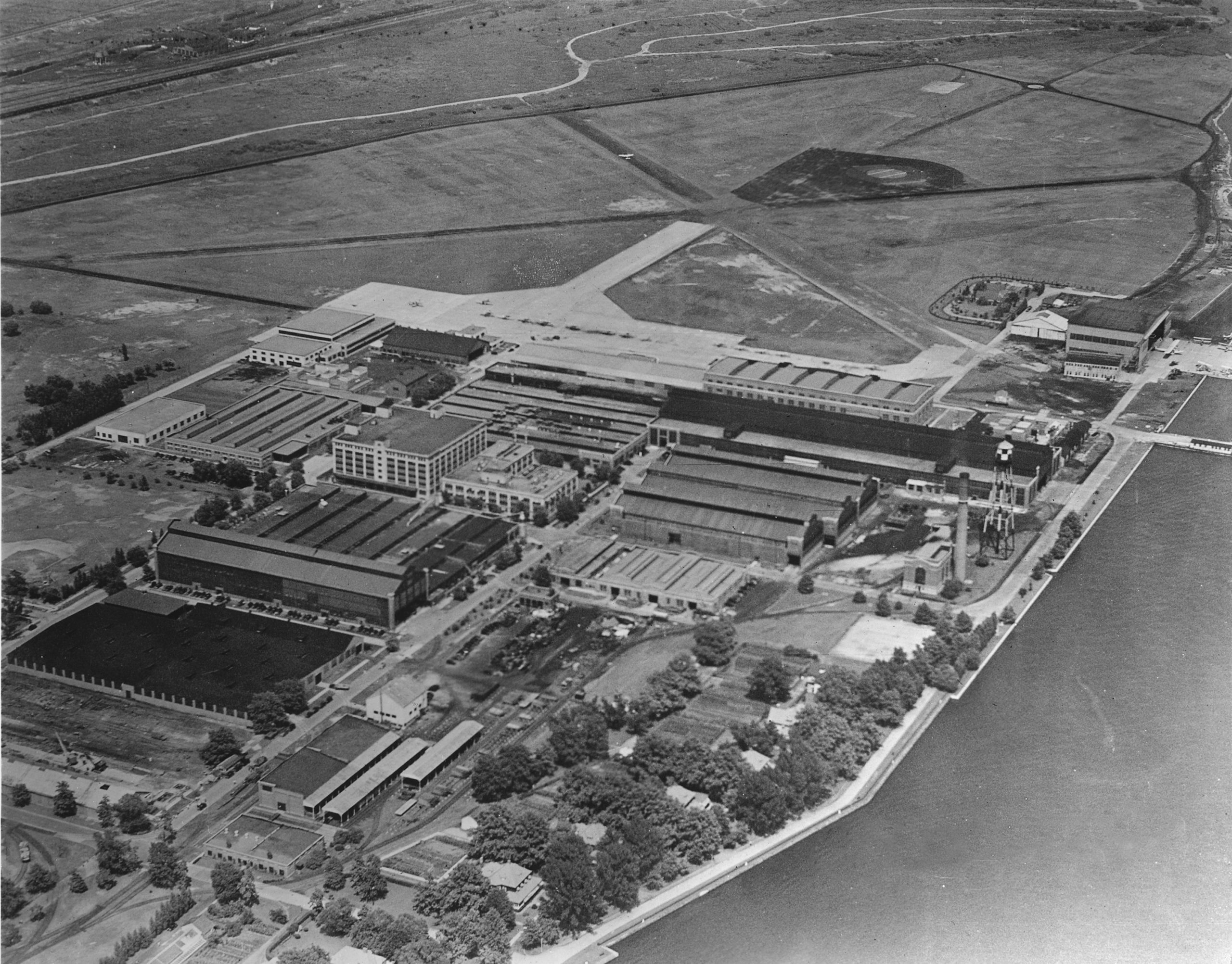

The aircraft were built by the Naval Aircraft Factory (NAF), the establishment of which was approved by the U.S. Secretary of the Navy in July of 1917, and by November of that year, the plant in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was completed. NAF was created due to the U.S. Navy Department’s rising need for aircraft when the U.S. entered World War I. Because there was a lack of an indigenous aircraft design and manufacturing program for equipping the armed services during the war, the United States was forced to manufacture existing British and French designs (such as the De Havilland DH-4). At the time, the Navy had a need for patrol flying boats, so the first Curtiss Model H-16 aircraft were completed by NAF in March 1918, and two were shipped off to RNAS Killingholme (England) in April. In 1921, NAF Philadelphia, as it became known, was placed under the supervision of the newly established Bureau of Aeronautics, and by 1922, the Navy had turned more toward its own internal engineering, design, evaluation, and testing of aircraft.

In 1922-23, NAF Philadelphia designers produced the rigid airship USS Shenandoah, which received its final assembly at NAS Lakehurst (New Jersey), which had the only hangar large enough to house it. During the course of World War II, NAF Philadelphia became involved in research relating to flying bombs and assault drones, cabin pressurization, plastic structural materials, adhesives, and magnesium aircraft components; and women were certainly a part of the workforce there, operating drill presses, for example. NAS Philadelphia’s operations were altered by the Vinson-Trammell Act of March 1934, signed by President Roosevelt, that provided for “not less than 10 percent of the aircraft, including the engines therefore…shall be constructed and/or manufactured in Government aircraft factories.” The Navy was in need of a more advanced primary trainer to replace the Consolidated NY-2 and NY-3, and in fact, in October 1934 the Bureau of Aeronautics ordered the “design and construct an experimental primary training airplane.” So starting with leftover aluminum angle from the building of the rigid airships USS Akron and USS Macon, the N3N was developed as both a land plane and seaplane. The prototype (designated XN3N-1) first flew in 1935 – based on the Navy’s designation system of 1922, the first “N” was for the aircraft class of trainer. The second “N” being the manufacturer code of Naval Aircraft Factory.

In 1936, the first of the N3N aircraft were delivered to the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Marine Corps, and a few to the U.S. Naval Academy. The U.S. Coast Guard acquired four from the U.S. Navy in December 1940 by trading four Grumman JF-2 Ducks. The primary reason for the trade was that the Coast Guard wanted to expedite pilot training, which was expanding in anticipation of war. The new trainers were given the tail numbers V193-V196, and they were initially assigned to CGAS Charleston, where initial flight training took place. Then V193 went to CGAS Elizabeth City, North Carolina; V194 and V195 went to CGAS St. Petersburg, Florida (I have seen evidence that aircraft here were used as basic trainers for Mexican Air Force pilots); and V196 went to CGAS Brooklyn, New York. The aircraft design featured an all-metal frame construction (NAF used aluminum rather than steel); the nose up to the firewall, as well as the tail fin, were metal-covered, while the rest of the aircraft was covered in Grade A cotton, as was common for the time (restorations typically use Dacron).

The port side of the fuselage was built with five access panels for inspection and maintenance. It was factory-equipped with an engine cowling, but mechanics preferred to remove them for easy maintenance since they did not offer much improvement in drag reduction. The production models were powered by a Wright R-760-2 Whirlwind radial engine with a hand-crank that turned the inertia flywheel until sufficient momentum was built and the T-handle starter was pulled. Communication from the instructor in the front seat to the cadet in the aft seat was through a speaking tube (cones connected by an air pipe). The U.S. Navy primary trainers were painted Chrome Yellow for maximum visibility, whereas the U.S. Army painted their primary trainer fuselages blue and the wings and tail surfaces Chrome Yellow, and the U.S. Coast Guard painted their aircraft in gray or blue-gray.

Production of the Canary ended in January 1942, but the type remained in use as a trainer through the rest of World War II and ultimately was one of a small number of aircraft designed and built by a factory that was federally funded for the U.S. Navy. There was resulting controversy over NAF Philadelphia from the outset in that it was considered in direct competition with the civilian industry and part of the reason the project was disestablished and production ceased in 1945 ( in January of 1922, Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, chief of the newly formed Bureau of Aeronautics, issued a statement stating that “the NAF is to all intents and purposes no longer an aircraft factory, but a combination of naval aircraft base, naval aircraft storehouse, naval aircraft experimental station, and in general a naval aircraft establishment…. It is not the policy of the department to go into production of aircraft at the Naval Aircraft Factory.”).

However, NAF Philadelphia produced a range of aircraft during its existence. After World War II, most N3N-3 aircraft were declared surplus except for about 100 that the Navy kept to provide orientation rides for midshipmen at the Naval Academy in the seaplane configuration. They continued in such non-trainer use until 1959, with the last of the aircraft stricken from military inventory in 1961, making the Canary the last biplane in U.S. military service. Surplus N3Ns could be purchased for about $500 and were, in some cases, converted to sprayers or crop dusters; some were fitted with water tanks and doors and thus became some of the earliest fire bombers ever flown. My photos at Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum in McMinnville, Oregon.

Editor’s note: This aircraft, N3N-3 Bureau Number 2831, was officially accepted by the US Navy on April 17, 1941, and assigned to Naval Air Station Grosse Ile, Michigan to be used for primary flight training by naval aviation cadets. On February 3, 1943, the aircraft was relocated to Naval Air Station Squantum, Massachusetts, but was later stricken from the US Navy’s inventory on September 28, 1943. After the war, it was initially flown with the FAA N-number N347AG before receiving its latest N-number, N3NN, in November 1971. In 1981, the aircraft was purchased by retired naval aviator, Princeton graduate, and businessman Ernest E.H. McCall of Portland, Oregon, who maintained and flew the aircraft privately before donating his N3N-3 to the Evergreen Aviation and Space Museum in 2008.

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.