“Vintage Aviation News staff did not write this article; the content comes via our partners who wish to help support our website.”

Neither cameras nor human memory is capable of freezing the moment in time with every single detail intact. The colors fade eventually, and the forest can never be visible behind the trees because even if a specific second is immortalized on tape, there is the entire unseen world that exists beyond it. People have always felt fascinated with Earth, and ever since technology began to develop, we’ve been trying to find a way to monitor it. Today, by usingSentinel-1 data to see the intricacies of the land, water bodies, species migrations, and disaster impacts, we can observe the entire planet exactly as it is. How did we get to this point, though, and what other technologies have given us the space-level opportunities we have now?

The Dawn of Aerial Observation: Airplanes and Photographs

The first real step to capturing the way our world looks was made in 1858, when French inventor Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, also known as Nadar, took the first aerial photos ever. He relied on the tethered balloon, reaching an altitude of sixteen hundred feet and observing the land from above. Nadar’s example inspired people all over the world, so naturally, more similar explorations unfolded. The next notable shift happened during World War I, and it comprised the following steps:

- Starting with the end of 1915, special photo-reconnaissance units were sent to the Western Front to capture the layout of the enemy forces.

- Pilots began to strap cameras like the Kodak Vest Pocket to their chests, taking more and more photographs of different locations.

- Gradually, the British Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and French Air Service developed custom-built cameras that could be attached to the aircraft frames.

- This allowed taking aerial photos from better angles and in safer conditions.

Overall, in this period, over 15,000 aerial photos were produced. Some of them survived to this day — they can be found online or in different museums dedicated to WW1 or aerial photography as a whole.

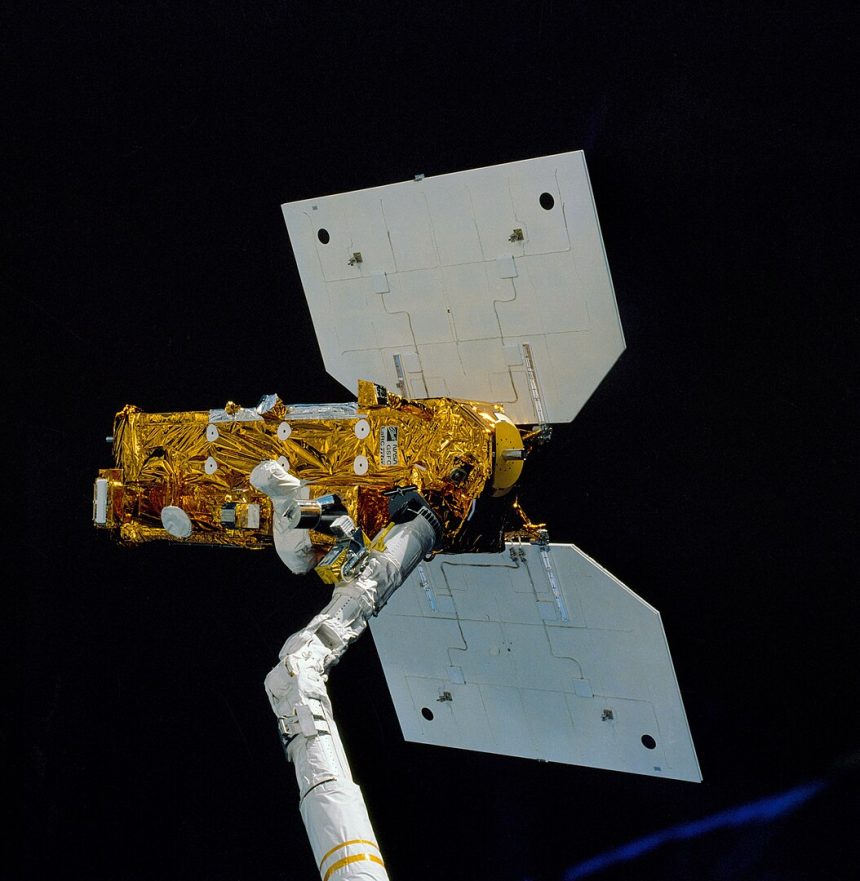

Going Beyond the Atmosphere: The Power of Satellites

Technologies continued to develop over the decades following WW1, expanding the pool of Earth observation possibilities. In 1957, the first space experiment was carried out with the help of Sputnik 1, the First Artificial Earth Satellite (AES). It allowed scientists to measure atmospheric density, observe orbital decay, and collect information about Earth’s upper atmosphere in general. TIROS-1 became the next milestone that bridged the gap between the past and the future of Earth observation technologies. This satellite carried two cameras and a tape recorder to capture cloud images, which allowed people to start observing the weather and predicting the upcoming hurricanes However, all these accomplishments paled in comparison to Landsat 1, which was launched in 1972. It monitored Earth’s natural and human environments, capturing imagery in 4 spectral bands that allowed scientists to distinguish between vegetation, soil, and water bodies. During the 6 years of work, Landsat 1 immortalized 75% of Earth’s total surface, depicting fires, animal life, and different geographical communities. It led to global changes, with people discovering new islands and taking a new, in-depth look at the Earth and everything it has to offer.

The Bridge to Modernity: SAR and Sentinel-1

The Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) was another relevant stage of development in the sphere of Earth monitoring. By using radio waves, it began to take images of Earth regardless of weather conditions. Later, in 2014, SAR became one of many parts of Sentinel-1, a constellation of two satellites that revealed an ocean of new opportunities to everyone interested in observing the Earth. Its key features include:

- Extremely wide coverage of up to 400 km and resolution down to 5 m.

- Short revisit time, with the satellites capturing new images of the same territories every 6 days.

- Open data, which lets any interested person access Sentinel archives and monitor what is happening.

- All-weather, day-and-night radar imagery that can be accessed any time.

Sentinel became a true revelation in our world. With its help, we can guide rescue teams during disasters, observe how poaching and deforestation affect wildlife, note down unexplored migration patterns, and discover new territories. With millions of aerial photographs taken from the sky and space over decades, Earth is no longer a mystery to us. In 2025, we know more about it than the scientists of the 20th century dared to imagine.

New Potential Angles of Earth Exploration

Are modern technologies, along with Sentinel-1, the end of the technological revolution? Not at all. While we can already observe the Earth in every detail, spotting the problems, changes, and even crimes like deforestation, there is always room for further growth. Specifically, quantum sensors might start being implemented on a wide scale, improving image accuracy and expanding the possibilities of geophysical mapping. We might encounter new supplies of underground water reserves and mineral deposits with their help – and that’s just the beginning.

“Vintage Aviation News staff did not write this article; the content comes via our partners who wish to help support our website.”

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.