By Kevin Wilkins

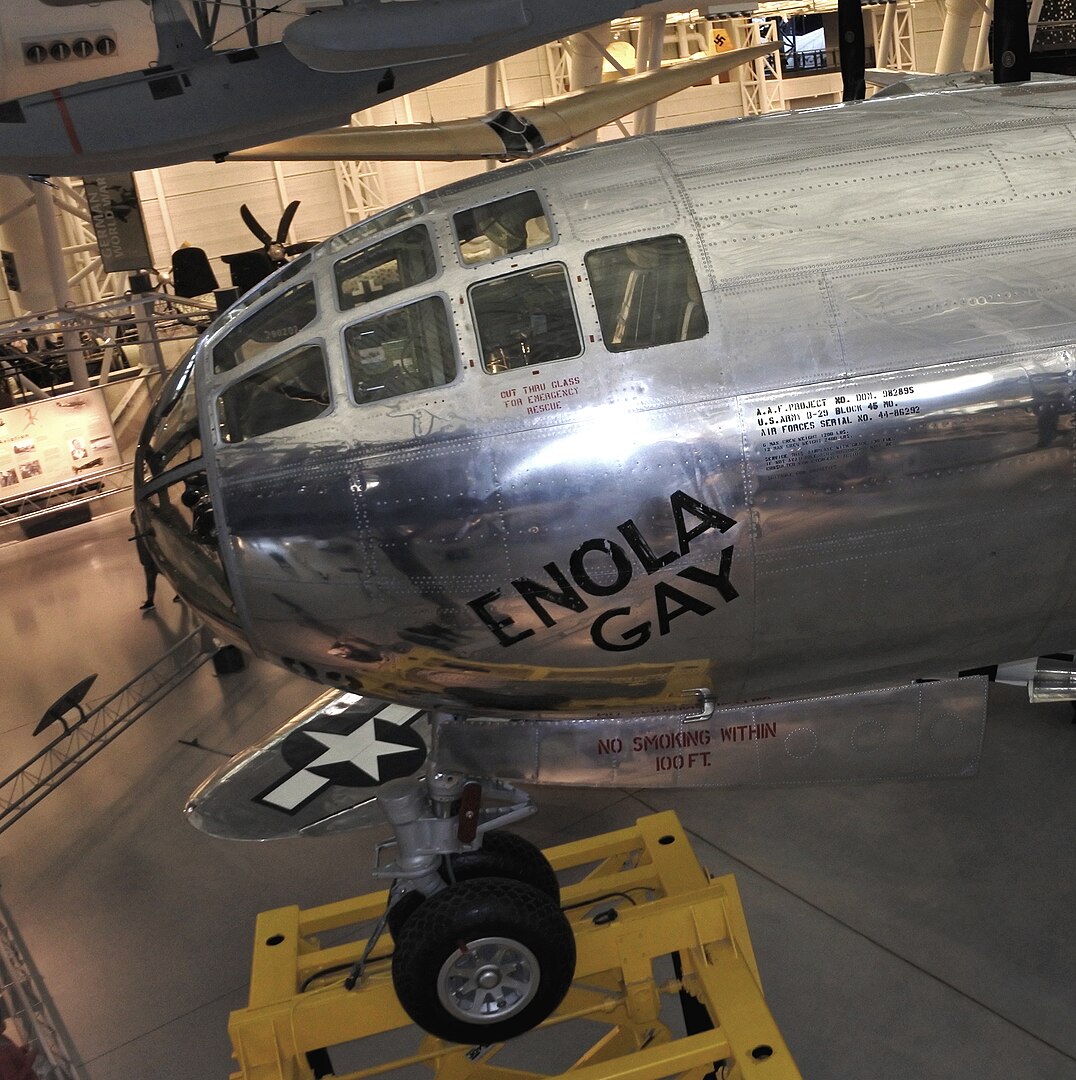

As August 2025 approaches, the world prepares to mark a solemn milestone: the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On August 6 and 9, 1945, two B-29 Superfortresses—Enola Gay and Bockscar—changed the course of history. Today, both aircraft are preserved as powerful reminders of that moment: Enola Gay is on display at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Virginia, while Bockscar resides at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Ohio.

These bombers were part of a top-secret mission known as Silverplate, the codename for the United States Army Air Forces’ role in the Manhattan Project. Initially used to describe the technical modifications required to equip the B-29s for atomic delivery, Silverplate eventually encompassed the entire training and operational framework that enabled the 509th Composite Group to carry out its mission.

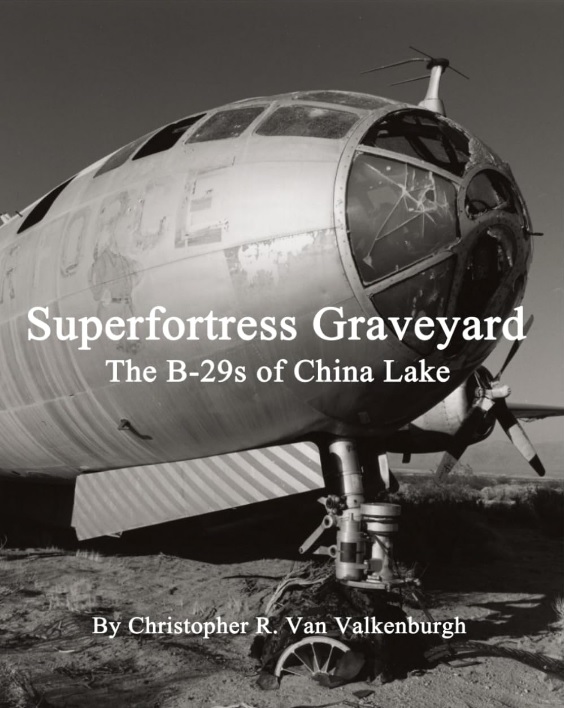

While Enola Gay and Bockscar survived the war and were preserved, three other Silverplate B-29s that played critical roles in the atomic bomb campaign were not so fortunate. After serving their purpose, they were quietly transferred to the Naval Ordnance Test Station at China Lake, California, where they were ultimately used for ground weapons testing and destroyed. Their remarkable stories are brought to life in Superfortress Graveyard – The B-29s of China Lake, a deeply researched chronicle by historian Christopher R. Van Valkenburgh. The book not only documents the serial production history of every B-29 ever built, but also provides the full biographies of these forgotten giants—down to the final scorch marks left in the desert. The book is available on Amazon, click HERE.

Among them was Full House, a Silverplate B-29 built under Block 36 as part of the final production run at the Glenn L. Martin plant in Omaha. Delivered in March 1945, Full House joined the 509th Composite Group at Wendover before heading to Tinian in June. Though it did not drop an atomic bomb, the aircraft flew multiple “Pumpkin Bomb” missions—dropping high-explosive replicas of the Fat Man bomb—over targets in Toyama, Niihama, Yaizu, and Ube in the final weeks of the war. On the day of the Hiroshima mission, Full House served as a backup aircraft, and for the Nagasaki bombing it flew a weather reconnaissance sortie. After the war, the aircraft returned to the United States, bounced between several bases, was converted to a trainer, and ultimately ended up at China Lake in 1956. There, it was subjected to weapons testing until it was destroyed in 1971. A complete profile of Full House is available in the book; click HERE.

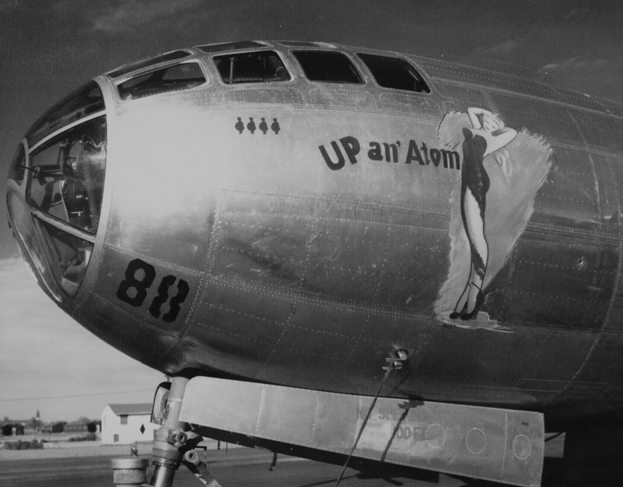

Another aircraft, Up an’ Atom, shared a similar trajectory. Like Full House, it was part of the Silverplate fleet, delivered in April 1945 and sent to the Pacific island of Tinian to support bombing operations. Although it did not participate directly in either atomic mission, its crew—known as B-10—flew aboard Necessary Evil, the camera aircraft that documented the Hiroshima blast. After the war, Up an’ Atom was used in Operation Crossroads, the postwar nuclear test series at Bikini Atoll, before being converted to a radar calibration platform. It too was sent to China Lake in the late 1950s and ultimately destroyed. A complete profile of Up an’ Atom is available in the book; click HERE.

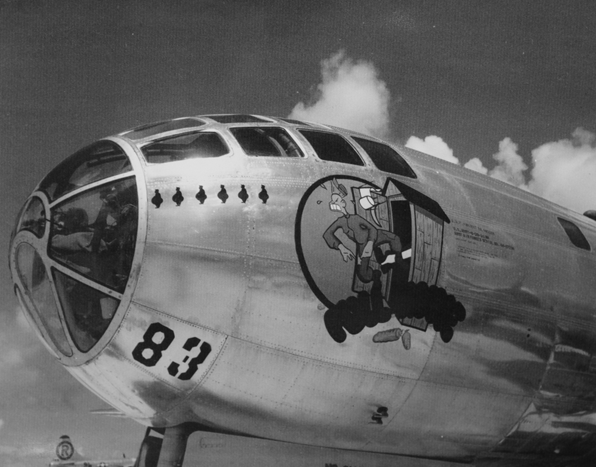

The third aircraft, Necessary Evil, played a more visible role in history. On August 6, 1945, it flew alongside Enola Gay during the bombing of Hiroshima, carrying scientific observers and cameras to document the detonation. Modified under the Silverplate program and delivered just weeks before the mission, it bore the deceptive tail markings of the 6th Bomb Group to confuse enemy observers. After its moment in history, Necessary Evil continued flying—supporting nuclear test programs, serving in the 509th, and eventually being relegated to radar evaluation duties. Like its sister ships, it ended its life at China Lake. A complete profile of Necessary Evil is available in the book; click HERE.

Together, these three B-29s represent a forgotten postscript to one of the most pivotal chapters in aviation and military history. Their names and missions are known to scholars and enthusiasts, but their fates—becoming test hulks in a remote stretch of California desert—are far less familiar. Superfortress Graveyard brings these stories to light, drawing from deep archival research, declassified military documents, and haunting photographs of the aircraft as they sat, crumbling and weathered, beneath the desert sky. It is a tribute not just to machines, but to memory itself—and to the complicated legacy of the aircraft that helped usher in the atomic age.

About the Author

These old War birds are a piece of History and when you loose history you loose a lot . It is good to see some still Flying today and we had FiFi in Our Hanger that was so cool like Royalty coming for a visit

I was stationed at China Lake from 1968 to 1970 attached to VX-5 Squadron and witnessed the destruction of two B29s. My feelings then and now were “what a shameful waste of material and historical value.”

Hello Bruce. I visited China Lake with a USAF Major and taken onto the range to preview the recovery of a B-47. Nearby was the wreck of a B-29 that had been bulldozed into a ravine. The entire aircraft was there and I picked up a few pieces for my collection. Did you take any photos of the two B-29’s that you saw destroyed? Thanks for your service.

B29’s flew through the atomic clouds in the Pacific tests and landed at McClellan AFB.

They were hot so got washed off on the tarmac. The runoff went into Magpie Creek. The Creek was discovered to be hot so rather than remediation it was covered in cement.

Or so I heard.