If there is one singular airplane in history that is more controversial than any other, it is a B-29 Superfortress that carries the name Enola Gay. For some, it is the instrument that ended World War II, and for others, it represents the beginning of a new horror unleashed upon the world. As one can imagine, an item that continues to stir as much controversy as the Enola Gay does, some 80 years after the bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, has presented a challenge for the curators of the Smithsonian Institution National Air and Space Museum, charged with being its historical custodians. But in focusing on how the Enola Gay has been preserved, and how its controversial legacy has been interpreted and reinterpreted since the end of World War II, students of history may come to understand the nuances of how similar artifacts can be contextualized and explained, while recognizing the need to preserve such items from our shared history.

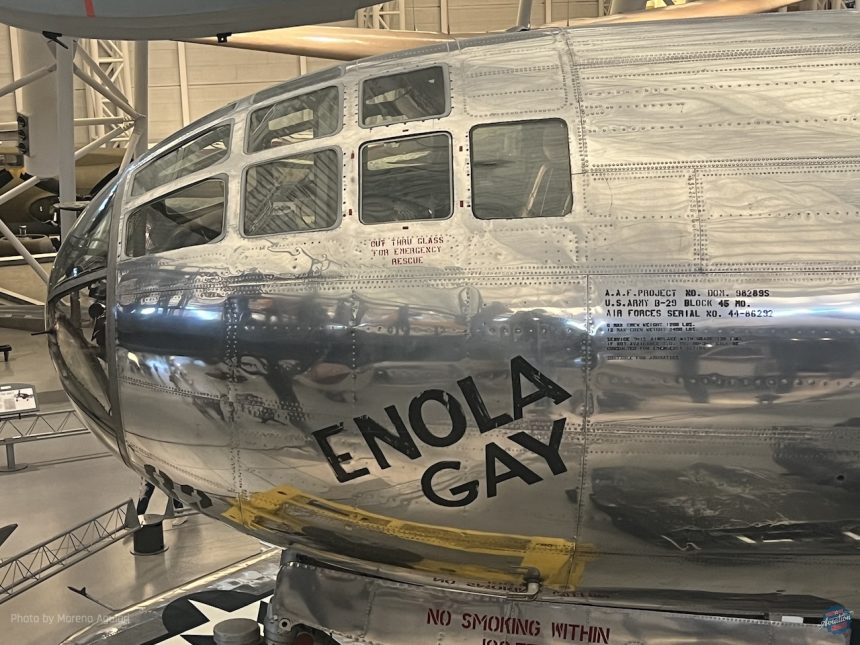

While the story of how the atomic bomb was created through the Manhattan Project has been told time and time again in books, television documentaries, and even blockbuster movies such as Oppenheimer, and that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have also been the subject of countless books, films, and works of art in both Japan and the United States, the story of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress 44-86292 Enola Gay following the bombing of Hiroshima will be the subject of this article. Built outside Omaha, Nebraska, at the Glenn L. Martin Bomber Plant in Bellevue, aircraft 44-86292 was personally selected for modification alongside 14 other B-29s in Bellevue by Lt. Col. Paul W. Tibbets, Jr., commander of the 509th Composite Group, during his inspection of the factory on May 9, 1945. Nine days later, on May 18, 44-86292 was accepted into the United States Army Air Force and joined the 393d Bombardment Squadron, Heavy, 509th Composite Group. On June 14, 1945, the aircraft was flown to Wendover Army Air Field, Utah, by its newly assigned crew, led by Captain Robert A. Lewis. Through training missions in the United States and the flight to North Field on the island of Tinian, Lewis was the aircraft’s commander.

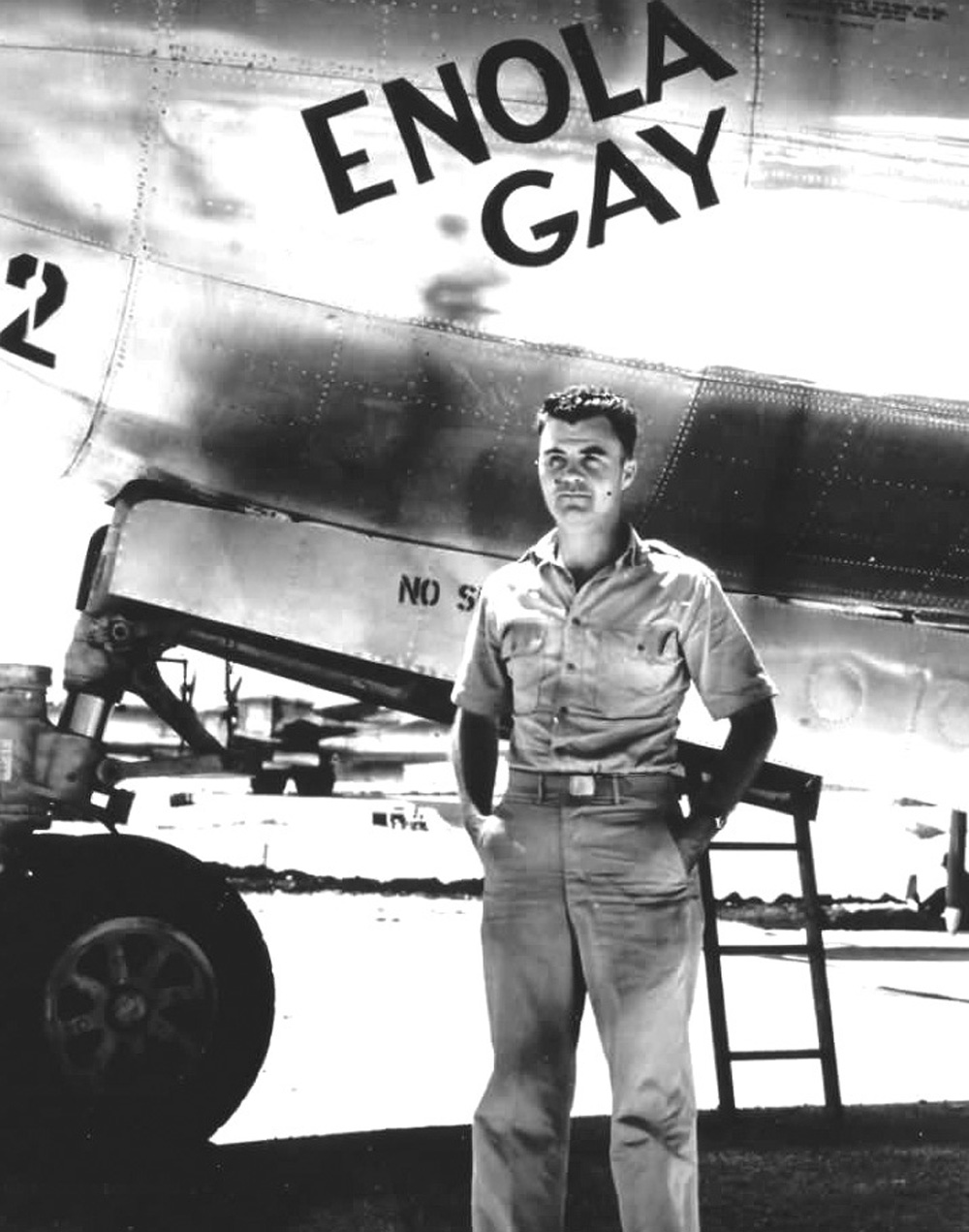

When it was decided that the first atomic bombing mission in history would be carried out on August 6, 1945, with the primary target being the city of Hiroshima, Colonel Tibbets took command of the aircraft on August 5. Much to the chagrin of Captain Lewis, Tibbets ordered that the name of his mother, Enola Gay, be painted on the aircraft. Tibbets had thought back to his mother, “whose quiet confidence had been a source of strength to me since boyhood, and particularly during the soul-searching period when I decided to give up a medical career to become a military pilot.”

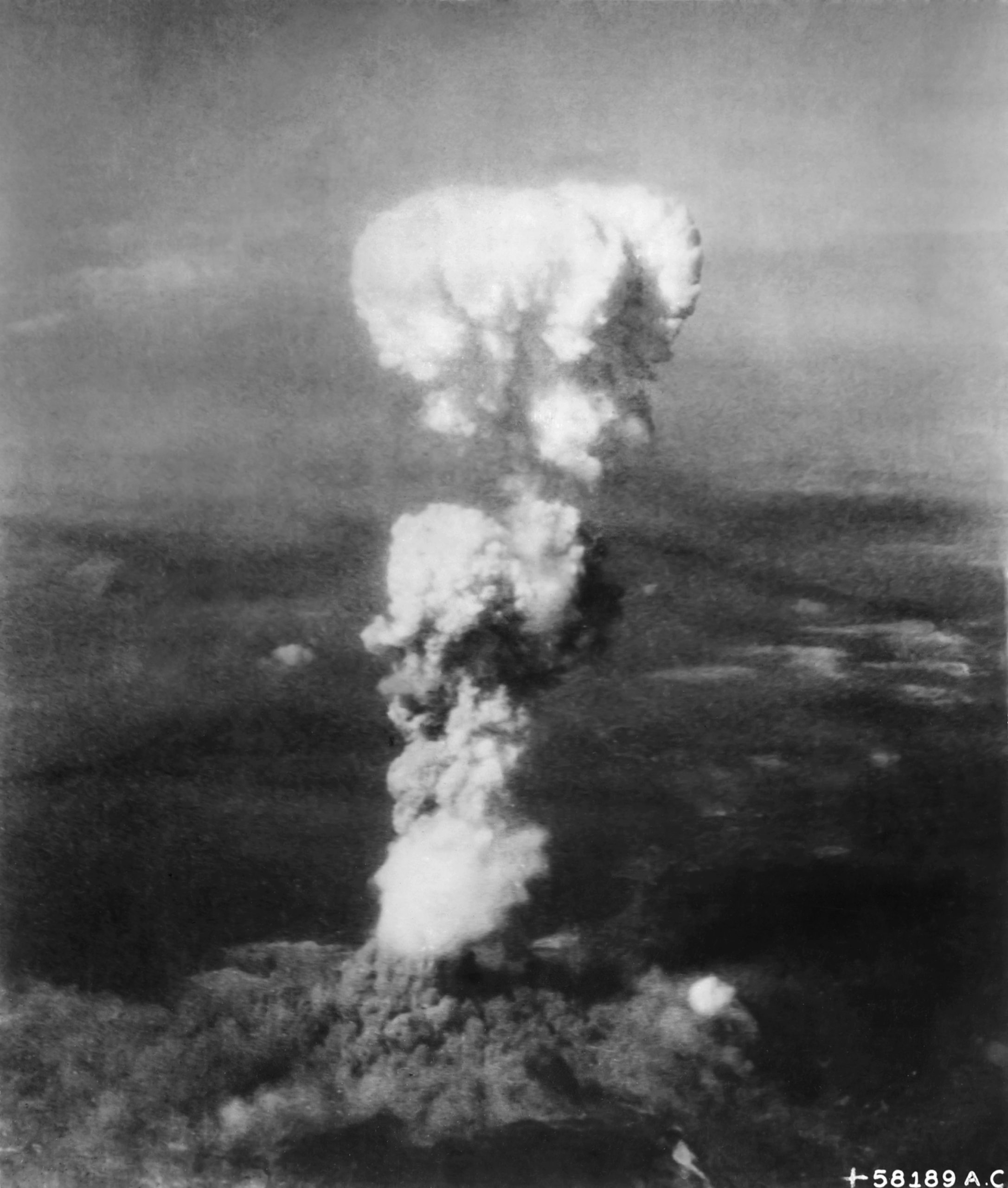

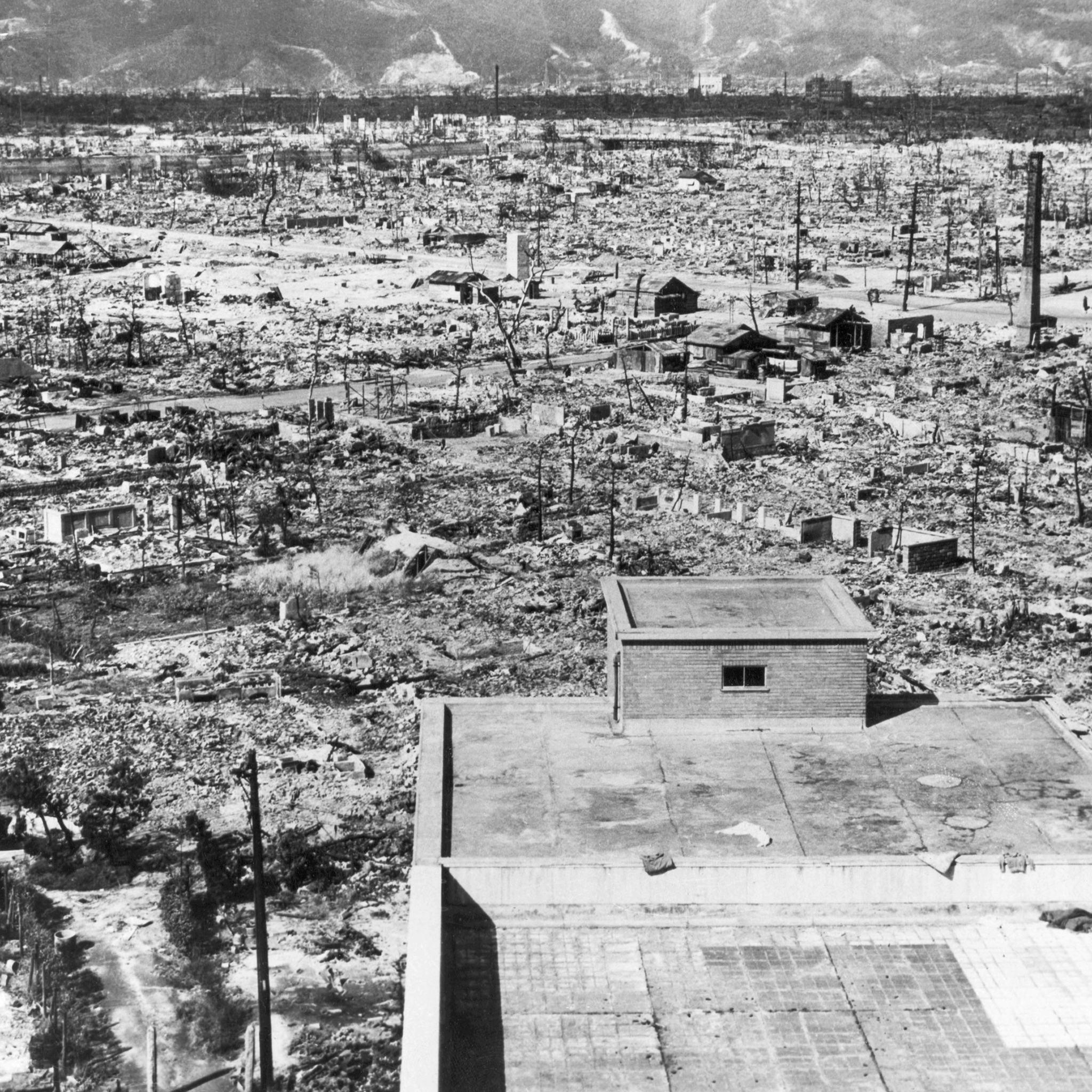

At 2:45 am local time, the Enola Gay rose from Tinian for the six-hour flight to Hiroshima. At around 7 am over Hiroshima, the B-29 Straight Flush, acting as weather reconnaissance over Hiroshima, reported that conditions were right for the preferred visual bombing approach. At 8:15 local time, the atomic bomb Little Boy was released from the Enola Gay from an altitude of 31,060 feet (9,470 m) over the center of Hiroshima. Ostensibly, the objective of bombing Hiroshima was to destroy the military-industrial facilities there, such as the headquarters of the Second General Army and Chūgoku Regional Army, the Army Marine Headquarters at Ujina port, and the facilities for maintaining military supplies and shipping. However, the majority of the area was still populated by civilians, as had been the dozens of cities that had already seen extensive firebombing from conventional explosives dropped by thousands of other B-29s.

Fifty-three seconds later, after falling to around 1,968 feet (600 m) above the city, Little Boy detonated. The resulting blast and firestorm killed some 70,000–80,000 people and injured another 70,000, many of whom would suffer lifelong effects from radiation exposure. There were also around 20,000 Japanese soldiers killed, along with 20,000 Korean slave laborers and 12 Allied prisoners of war (POWs).

Later that day, at 2:58 local time, the Enola Gay landed back at North Field on Tinian after 12 hours and 13 minutes in the air, from which it departed at 2:45 am local time. Immediately after landing, Tibbets was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross by General Carl Spaatz. While postwar activists, Hiroshima survivors, and scholars bring up the destructive and cataclysmic costs of the bombing, many Americans at the time, especially the thousands of soldiers preparing to embark on the planned amphibious invasion of Japan, saw the events of Hiroshima as a decisive moment that could see a quick end to the Second World War.

On August 9, 1945, the B-29 named Bockscar, flown by the crew led by Major Charles W. Sweeney, set off with the nuclear bomb Fat Man. Originally, Bockscar’s primary target was the city of Kokura, over which the Enola Gay fulfilled the role of weather reconnaissance. While the weather over Kokura was initially clear, the conflagration of clouds and smoke from the previous day’s bombing of nearby Yahata, plus the Bockscar’s crew waiting over 30 minutes for the arrival of the observation/photography aircraft, the B-29 Big Stink, led Bockscar to switch to its secondary target, Nagasaki.

On the same day that Bockscar bombed Nagasaki rather than Kokura, the Soviet Union, having previously been neutral in the Pacific Theater, invaded Japanese-occupied Manchuria (known to the Japanese as Manchukuo). On August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito publicly addressed his nation for the first time to announce that Japan would “accept the terms of the Joint Declaration”, saying that “the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage”. He also mentioned the atomic bombs in his address to the Japanese nation, stating that “the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization”.

With the end of the Second World War, the 509th Composite Group returned to the continental United States to be reassigned to Roswell Army Airfield, New Mexico. The Enola Gay departed on November 6, 1945, and arrived at Roswell two days later. Though the historic aircraft remained in service with the 509th, discussions about preserving the aircraft for future generations had already begun, with the Smithsonian Institute being considered as a primary candidate. Yet although Enola Gay’s combat career had ended, the aircraft would be flown on one final mission. As the wartime alliance between the Western Allies (the United States and the United Kingdom) and the Soviet Union began to erode as a result of the ideological differences between the capitalist West and the communist East, the United States maintained a monopoly on nuclear weapons. Its strategists decided to conduct tests against now surplus warships at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands in what would become Operation Crossroads. The 509th Composite Group flew their aircraft, then the only planes in the world capable of deploying nuclear weapons, from Roswell to Kwajalein Atoll, which was to serve as their base of operations for the duration of Operation Crossroads.

The Enola Gay took off from Roswell, New Mexico on April 29, 1946, arriving at Kwajalein on May 1. Though it remained present at Kwajalein, the Enola Gay was never used to drop any bombs during the tests, and departed for the United States on July 1, the same day that the B-29 Dave’s Dream (formerly known as Big Stink) dropped the Fat Man-type bomb Glida on the target ships at Bikini Atoll. The next day, Enola Gay landed at Fairchild-Suisun Army Airfield (now Travis Air Force Base), California.

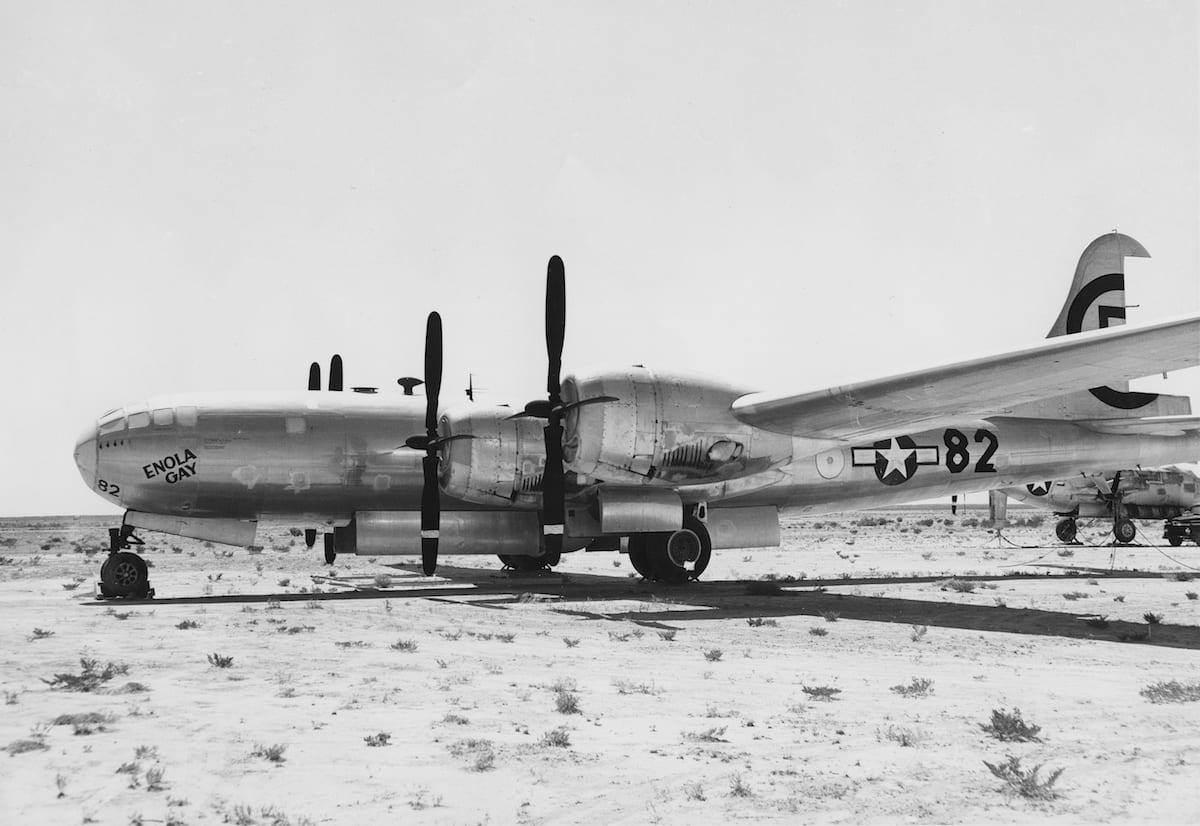

With the return of the Enola Gay back to the United States, the decision to set aside the aircraft for preservation was finalized, and Enola Gay was flown to Davis-Monthan Army Air Field on July 24, 1946 for storage. One of the biggest proponents for preserving the Enola Gay was Paul . Garber, curator of the aircraft collection of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Garber, who had been working for the Smithsonian since 1920, had dreams of a dedicated aeronautical museum among the prominent monuments and memorials in the nation’s capital, and was always on the lookout for aircraft of historical merit.

On August 30, 1946, the United States Army Air Force formally transferred the Enola Gay to the Smithsonian’s newly created National Air Museum, which itself had only been established on August 12. But lacking any space in Washington, D.C. to display the massive bomber, the Enola Gay stayed in the desert sand at Davis Monthan for nearly three years, when the aircraft was prepared to fly to Orchard Place Airport (now Chicago O’Hare International Airport) in the Chicago suburb of Park Ridge, where a former Douglas C-54 assembly plant was converted into a storage facility for the National Air Museum’s new collection of WWII Allied and Axis aircraft. On July 3, 1949, Paul Tibbets himself flew the aircraft to Orchard Place. There, the aircraft would remain until the Korean War, when the Air Force ordered the Smithsonian to vacate the Park Ridge facility, leading to the mass movement of the Smithsonian’s collection to Maryland.

Once again, however, the Smithsonian did not have any accommodations for the Enola Gay, which on January 12, 1952, was flown to Pyote Air Force Base, Texas, for outdoor storage, alongside other surplus B-29s. Another aircraft from the National Air Museum’s collection was also flown into Pyote for storage: Boeing B-17D Flying Fortress 40-3097, better known as the “Swoose” (which is now under restoration at the National Museum of the United States Air Force following its transfer from the Smithsonian in 2008). For another year, the Enola Gay waited in the desert for the time to be brought to Washington.

By 1953, the Smithsonian had selected a plot of undeveloped federal land outside of Suitland, Maryland, which would eventually become the Silver Hill Storage Facility. On December 2, 1953, the Enola Gay made its final flight, taking off from Pyote to arrive at Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland. Upon arriving at Andrews, Garber and the rest of the National Air Museum staff hoped the Air Force would guard the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb in war, but they were to be disappointed. The Air Force concluded that it had no hangar space for either the Enola Gay or the B-17 The Swoose, which made its own arrival at Andrews three days after the Enola Gay on December 5, 1953.

The two aircraft were towed to a remote corner of the base, with no provision for guards, and exposed to the elements. Soon, both aircraft saw trespassers intrude on them and steal any loose items from their interiors as souvenirs. With the burglars came animal predation, as birds made nests all over the two bombers. Concerned over the deteriorating state of the Enola Gay and the Swoose, the Smithsonian sent its staff to disassemble the two aircraft and transport them to the Silver Hill facility. Work on the Enola Gay began on August 10, 1960. Over 11 months, the forward and aft fuselage sections were removed separately, the engines were dismounted from the wing, and the wings themselves were taken off the fuselage and disassembled into outboard and inboard sections. Furthermore, the empennage and propellers were taken from the tail and the engines, respectively, and it was not until July 21, 1961, that the last components left Andrews AFB for Silver Hill.

This was not the end of the controversy, however. By this time, the B-29 Bockscar (44-27297), which had dropped the atomic bomb Fat Man on the city of Nagasaki, had been placed on public display at the United States Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio, following its final flight from Davis Monthan to Wright-Patterson on September 26, 1961. The Enola Gay, by contrast, would be stored away from prying eyes at Silver Hill, which had gone from reclaimed marshland to a series of around 32 nondescript metal storage buildings. Although the controversy surrounding the morals and implications of the atomic bombings of Japan would only become more heated against the backdrop of the Cold War, the anti-war movement, and the anti-nuclear movement, with historians, strategists, philosophers, and students of all persuasions waging war with the pen as opposed to the sword, some of the surviving veterans of the 509th Composite Group turned their attention to the Enola Gay.

By 1980, two veterans of the 509th Composite Group, former pilot Donald C. Rehl of Fountaintown, Indiana, and former navigator Frank B. “Bud” Stewart of Indianapolis, felt outraged over the condition of the Enola Gay. As they saw it, the Smithsonian had been negligent in preserving the Enola Gay, and lobbied Paul Tibbets, Jr., now a retired Brigadier General, and Arizona Senator and 1964 presidential candidate Barry Goldwater to put pressure on the Smithsonian to either begin restoration efforts on the historic aircraft, or have it loaned to an affiliate museum. Goldwater had previously been one of the most prominent figures in Congress to advocate for the approval of a dedicated building for the National Air and Space Museum, and remained a staunch supporter of the museum since then. In 1982, proponents of restoring the Enola Gay received internal support from the Smithsonian. That year, curator Walter J. Boyne was made acting director of the National Air and Space Museum before becoming the museum’s official director on February 10, 1983. Boyne was a former B-52 pilot and a prolific aviation historian and vowed to make the Enola Gay’s restoration one of his top priorities.

Shortly before the 39th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, retired Brig. Gen. Paul Tibbets made a visit to see the Enola Gay. Since he had not flown the aircraft to Pyote or Andrews, it was his first time seeing the aircraft since 1949, when he flew it into Orchard Place Airport. Though Tibbets was never apologetic over the Hiroshima mission, and often said he would fly the mission again if necessary, he recalled his first reunion with the aircraft as “A sad meeting. [My] fond memories, and I don’t mean the dropping of the bomb, were the numerous occasions I flew the airplane…. I pushed it very, very hard and it never failed me…. It was probably the most beautiful piece of machinery that any pilot ever flew.”

Later that year, on December 5, 1984, restoration of the Enola Gay officially began. It would be the most challenging aircraft restoration the Institution has undertaken so far. The staff at the Silver Hill Facility sought to preserve as much of the aircraft’s originality as possible, but the years of neglect would require the replacement or fabrication of many components on the aircraft. Two of the engines were sent to the San Diego Air and Space Museum in California to be restored, and curators placed distinguishing marks on every replacement or refabricated part to assist future curators in determining how many original and non-original parts are on the aircraft.

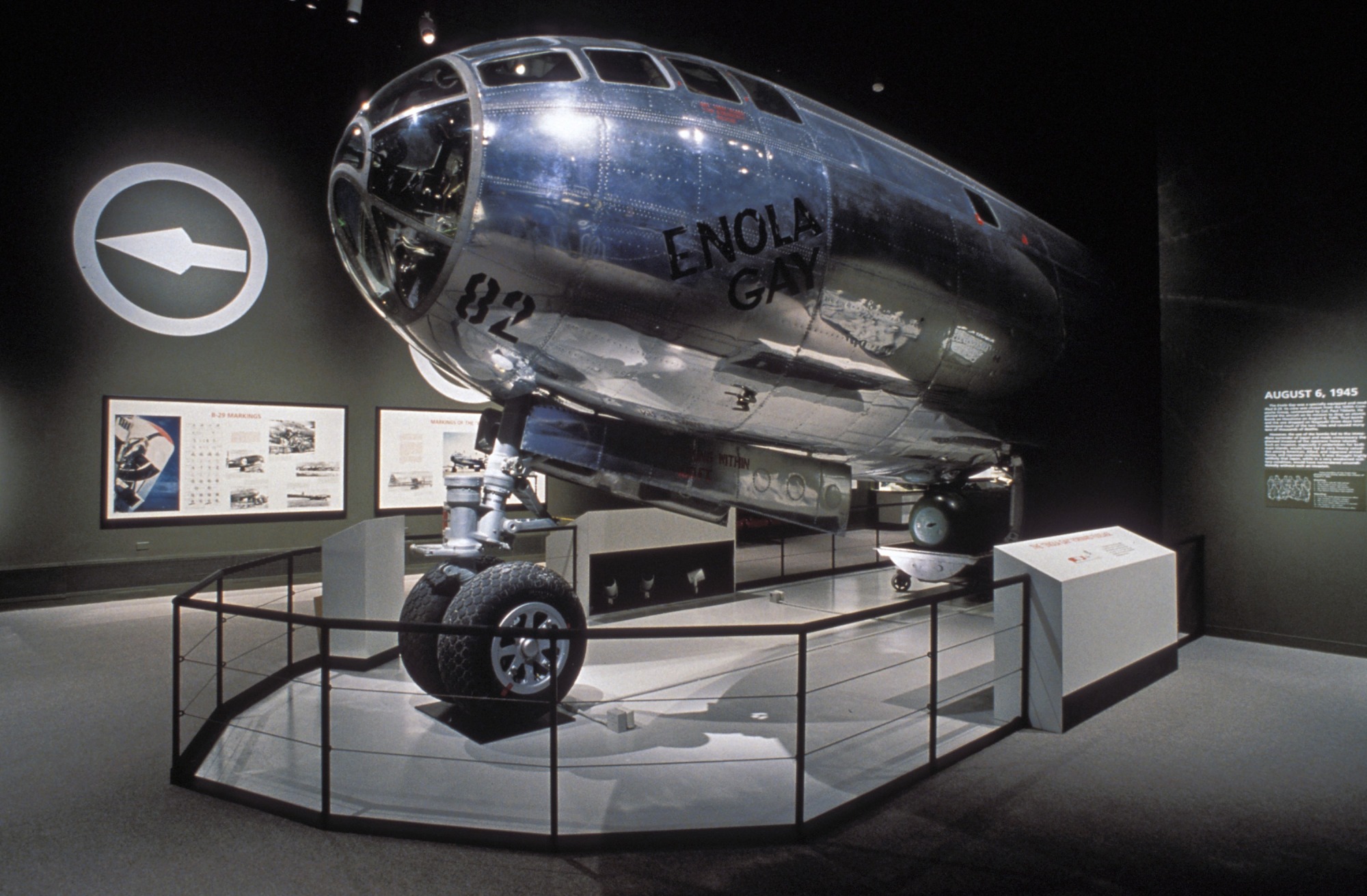

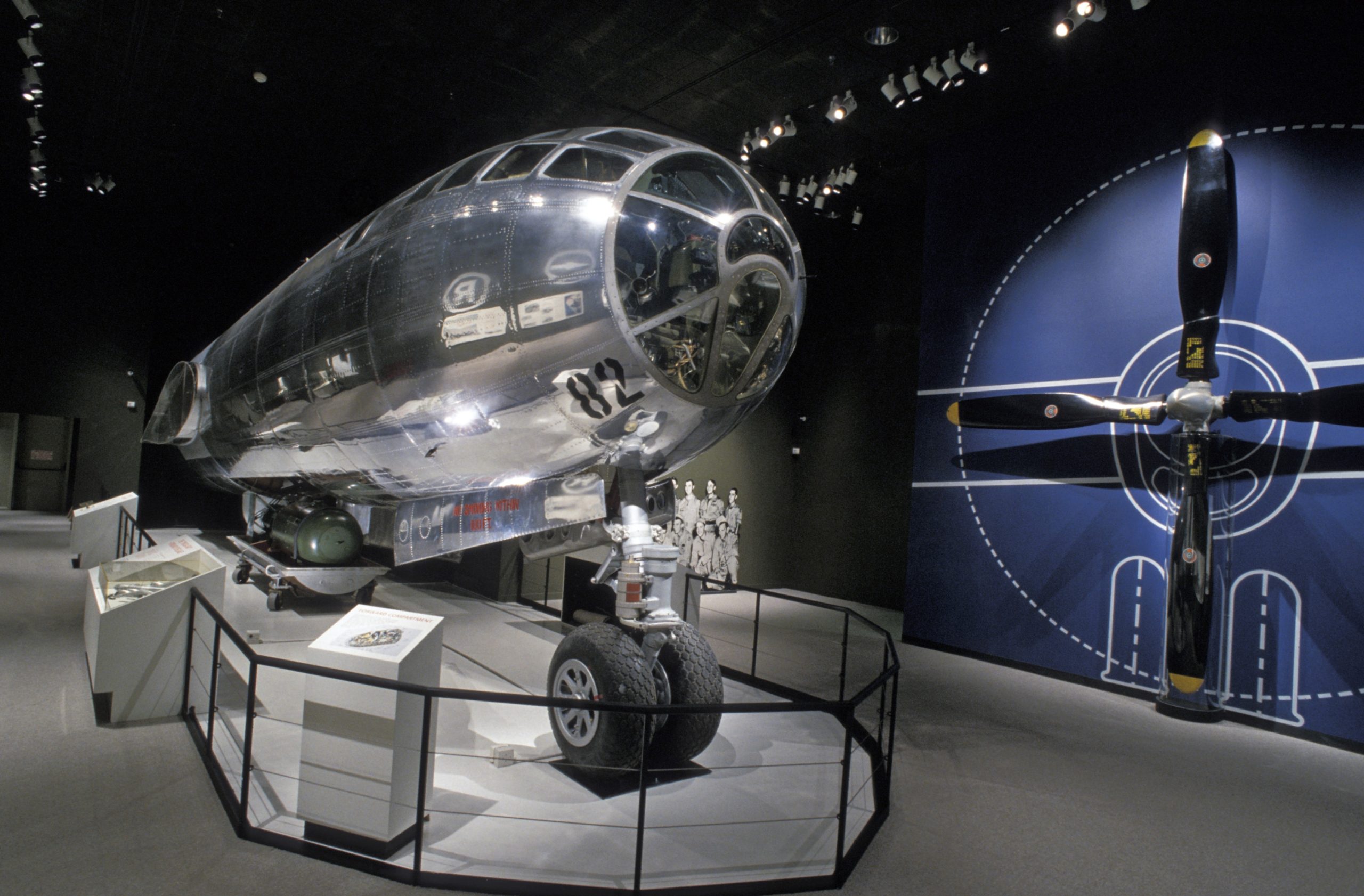

With the onset of the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombings and the end of WWII, the National Air and Space Museum spent the mid-1990s planning to create a special exhibit featuring parts of the Enola Gay for the first time. As the fully reassembled B-29 was too large to fit inside the museum building in downtown Washington, it was decided that while the remainder of the aircraft would remain under restoration at Silver Hill (later renamed in honor of Paul E. Garber), the forward fuselage would be the center of the exhibit.

The exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum was to be named The Crossroads: The End of World War II, the Atomic Bomb, and the Cold War. Even before the opening of the exhibit, however, the National Air and Space Museum found itself the target of public scrutiny from all sides. By the spring of 1994, the museum director was Czech-born Martin Harwitt, a former professor of astronomy at Cornell University. Organizations such as the American Legion and the Air Force Association, along with conservative media pundits, accused Harwitt of writing revisionist history, with two lines in the exhibit script being controversial for some: “For most Americans, this war was fundamentally different than the one waged against Germany and Italy—it was a war of vengeance. For most Japanese, it was a war to defend their unique culture against Western imperialism.”

Although the script preceding and including these lines read: “Japanese expansionism was marked by naked aggression and extreme brutality—the slaughter of tens of thousands of Chinese in Nanking in 1937 shocked the world. Atrocities by Japanese troops included brutal mistreatment of civilians, forced laborers, and prisoners of war, and biological experiments on human victims. In December 1941, Japan attacked US bases at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and launched other surprise assaults against Allied territories in the Pacific. Thus began a wider conflict marked by extreme bitterness. For most Americans, this war was fundamentally different than the one waged against Germany and Italy—it was a war of vengeance. For most Japanese, it was a war to defend their unique culture against Western imperialism”, critics also felt that the exhibit focused too much on the Japanese civilian casualties, with not enough focus on the notion that the atomic bombings saved more lives by ending the Second World War, and that the exhibit was interpreted as portraying the Japanese as victims rather than an aggressive, expansionist empire.

By contrast, anti-war and anti-nuclear activists felt that the exhibit did not go far enough in condemning the bombings for the thousands of lives lost and for the long-term effects of radioactive poisoning that stretched on into the postwar world, as well as discussing the bombing’s impact on the development of more powerful nuclear weapons. In the end, Harwitt resigned as museum director on May 2, 1995, following the cancellation of the original exhibit on January 30, 1995.

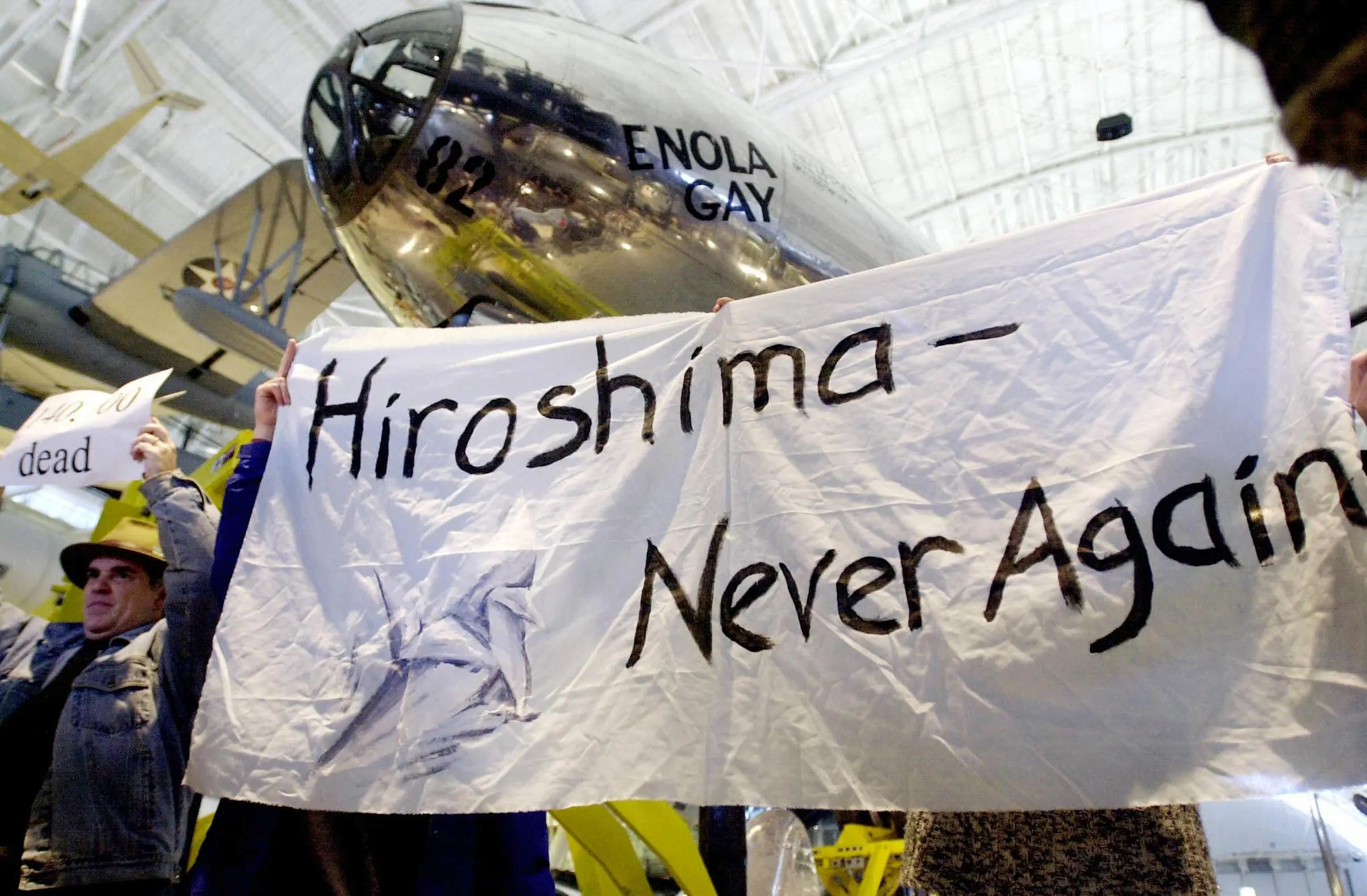

A new iteration of the Enola Gay exhibit, featuring the forward fuselage, vertical stabilizer, two propellers and an aileron, along with a full-scale replica of the Little Boy bomb, also featured a video presentation, notes on the production and operational service of the B-29, and a look into the extensive restoration efforts. This was opened on June 28, 1995. Protestors came to the museum, with many of them belonging to anti-war groups while others were members of the Historians’ Committee for Open Debate on Hiroshima. Though many of the protesters demonstrated outside the museum building, carrying signs and banners and distributing leaflets, others went inside, with around 20 individuals being ejected from the premises when they attempted to block access to the gallery or otherwise disrupt the exhibit. Despite this, over 3,200 people visited the Enola Gay exhibit that day. Four days later, on July 2, though, three demonstrators were arrested for throwing ash and human blood on the aircraft’s fuselage. In an earlier incident, another demonstrator had thrown red paint over the gallery’s floor.

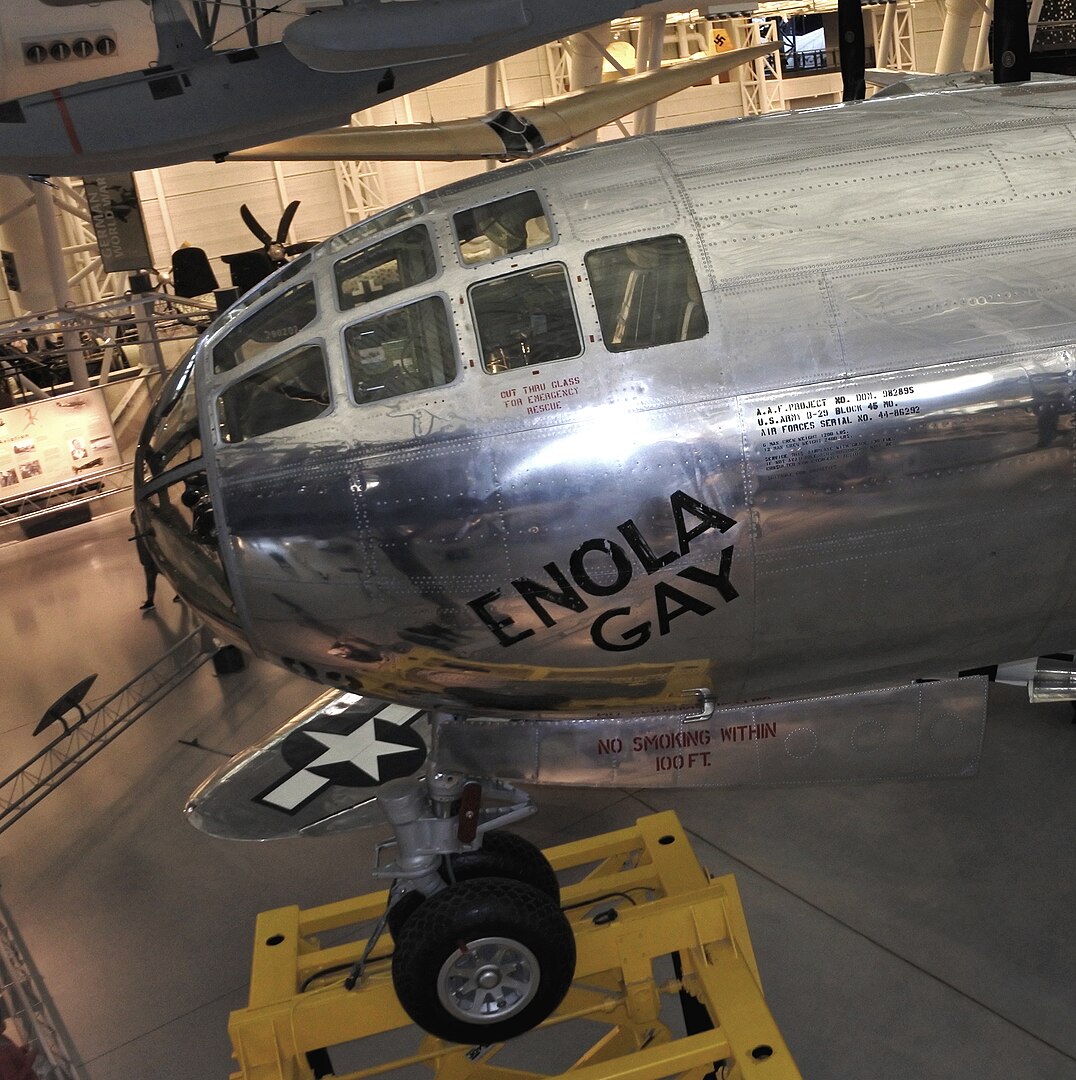

Despite this, the Enola Gay exhibit remained in place until it was closed on May 19, 1998, and the parts of the Enola Gay placed on display there were returned to the Garber Facility in Suitland. Meanwhile, the longtime plans for a second location for the National Air and Space Museum to be placed at Dulles International Airport near Chantilly, Virginia, finally came to fruition with a $65 million donation from Hungarian American aviation businessman Steven F. Udvar-Házy, leading to the creation of the Steven F. Udvar-Házy Center. Finally, there would be a place where the Enola Gay could be displayed as a fully reassembled B-29 Superfortress. Once the ten-story-high Boeing Aviation Hangar was completed, and the first aircraft were brought in, the Enola Gay’s components were shipped from the Garber Facility to the Udvar-Hazy Center from March through June 2003. One of the most significant milestones in the project occurred on April 10, when the wings of the Enola Gay were reunited with the aircraft’s fuselage for the first time since 1960.

By August 8, 2003, the Enola Gay was fully reassembled after approximately 300,000 work hours had been spent restoring the historic yet controversial aircraft. On December 15, 2003, the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center was officially opened to coincide with the centenary of the Wright Brothers’ first flights at Kittyhawk, North Carolina, with the Enola Gay being the centerpiece of the new museum’s World War II Aviation exhibition. Shortly after the opening, though, a group of demonstrators, including several Hiroshima survivors, gathered to protest the lack of descriptive information regarding the aircraft’s role in the bombing of Hiroshima. Two men were arrested (one for destruction of property and another for loitering) after a bottle of red paint was thrown against the Enola Gay, denting a panel on one side of it.

While the remaining protestors did not touch the Enola Gay, they made their opinions known. Among them was Hiroshima survivor Minoru Nishino, who had been two kilometers from the epicenter of the blast and still had the scars from the radioactive burns. Nishino reflected later that day in an article published for Qatari news outlet Al Jazeera: “This is the second time I have seen the Enola Gay. The first time was on 6 August 1945, when I saw it flying high in the sky. When I saw the Enola Gay today, I was overcome by anger.” Meanwhile, another survivor, Tamiko Tomonaga, who was then a nursing student of the Japan Red Cross Society in Hiroshima, said this of how the Enola Gay was displayed in the same article: “We would not mind the plane going on display if they showed the tragedy they caused.”

Some visitors made their objections to the protestors known to the demonstrators. One American visitor who wished to remain anonymous stated: “They (Japan) started the war by bombing our servicemen in Pearl Harbor; they should go and stand on the deck of the Arizona.” Meanwhile, the museum director and retired US Marine Corps General John “Jack” Dailey spoke on the lack of displaying the Hiroshima death toll next to the Enola Gay: “We don’t do it for other airplanes. From a consistency standpoint, we focus on the technical aspects.”

A more recent controversy involving the Enola Gay occurred in the spring of 2025 when the U.S. Department of Defense flagged photos of the Enola Gay during the Pentagon’s purge of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI)-related content following an executive order issued by President Donald Trump. The largely automated review process also flagged photos of the Tuskegee Airmen, female Marine Corps graduates, and commemorative posts for minority history months. You can read more about this incident in our article HERE. To this day, the Enola Gay is on display at the Udvar-Hazy Center. Though the ethics and the morals of the use of atomic weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki will remain a subject of debate among historians, philosophers, theologians, and analysts of all stripes, there is one immutable truth in all of this.

With the last surviving member of its flight crew on the Hiroshima mission, navigator Theodore “Dutch” Van Kirk having passed away in 2014, and many of the remaining survivors of the bombing of Hiroshima in their eighties to one-hundredths, the time will eventually come when the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki will no longer be in living memory. It is important, then, to maintain every trace our species has to this event, and for better or for worse, the B-29 Superfortress named Enola Gay is one of those links to that day when the world first became acquainted with the effects of nuclear war. Therefore, despite our disagreements over how we remember the Enola Gay, it must remain on display in an environment that seeks to appropriately contextualize the aircraft and ensure that it remains available for the public to visit for generations to come. For more information, visit www.airandspace.si.edu

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.

The Ebola Gay needs to remain on display as a tribute to the men, and women who built, flew, and maintained her in WW-2, and serve as an educational tool for people to learn about the Atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Anti war activists, and protesters should remember that if we didn’t nuke both Hiroshima, and Nagasaki, we, and our allies would’ve suffered horrendous casualties if the invasion of the Japanese Home Islands had proceeded as planned,so the two Atomic Bombings were a way to bring the war to a swifter end, along with saving millions of lives on both sides. Also, those people need to understand that every war that we’ve fought, gave them the right to speak out against our wars, but damaging exhibits, is not a good way to get the point out.

I agree with every word of John’s statement.

War is, unfortunately, War. And, looked at dispassionately and objectively, whether you inflict Death and Suffering in a few seconds, or over time, the result is going to be the same.

The two Bombs* brought a decisive End to the Pacific War; and an end to eight years of Japanese cruelty and barbarity; across China, Mainland Asia and the Pacific.

We have the same arguments here, in Britain; over the R.A.F Bombing of Germany and its Cities.

Many of those arguing against conveniently forgetting that Germany started the process;** with many British (and earlier European) Cities suffering Raids, some multiple Raids.

And, in the closing months (from 13 June ’44) of the European War, the Missile Attacks by both the V1 & V2 – ‘Vengeance Weapons’.

But remember also, had we not prevailed, the suffering in both Europe and Asia/Pacific would have continued, unabated.

So, Yes, War is a terrible thing.

But, when you’re fighting to stop an aggressive attacker (as we see in the Ukraine now) and to preserve Your Way Of Life, you must win, or be enslaved.

* Many will still argue that one Bomb was sufficient. Only God can answer.

** As Air Marshall Harris said of Germany, in 1942: ”They sowed the wind, and now they are going to reap the whirlwind.”