If there is any battle that could be called a turning point in the Pacific Theater of Operations during WWII, most historians agree that this would be the Battle of Midway. What the Imperial Japanese Navy had intended to be a decisive blow against the United States Navy’s carrier force became an ambush that put the Japanese war effort in the Pacific on the defensive, and signaled the start of the American momentum that led to the end of WWII. Yet as the Second World War now fades out of living memory, that leaves us who remain with the stories and artifacts left behind. Though Midway Atoll remains a small windswept island serving as a refuge for ocean-going birds, one tangible link to one of the most pivotal battles in the history of naval aviation can be seen at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida, where the last surviving airplane to have fought in the Battle of Midway, a Douglas SBD Dauntless, has found a special place of honor in which to rest and to educate the public on this key event in world history. But the Battle of Midway, cataclysmic as it was, is only a small part of the aircraft named “Midway Madness”.

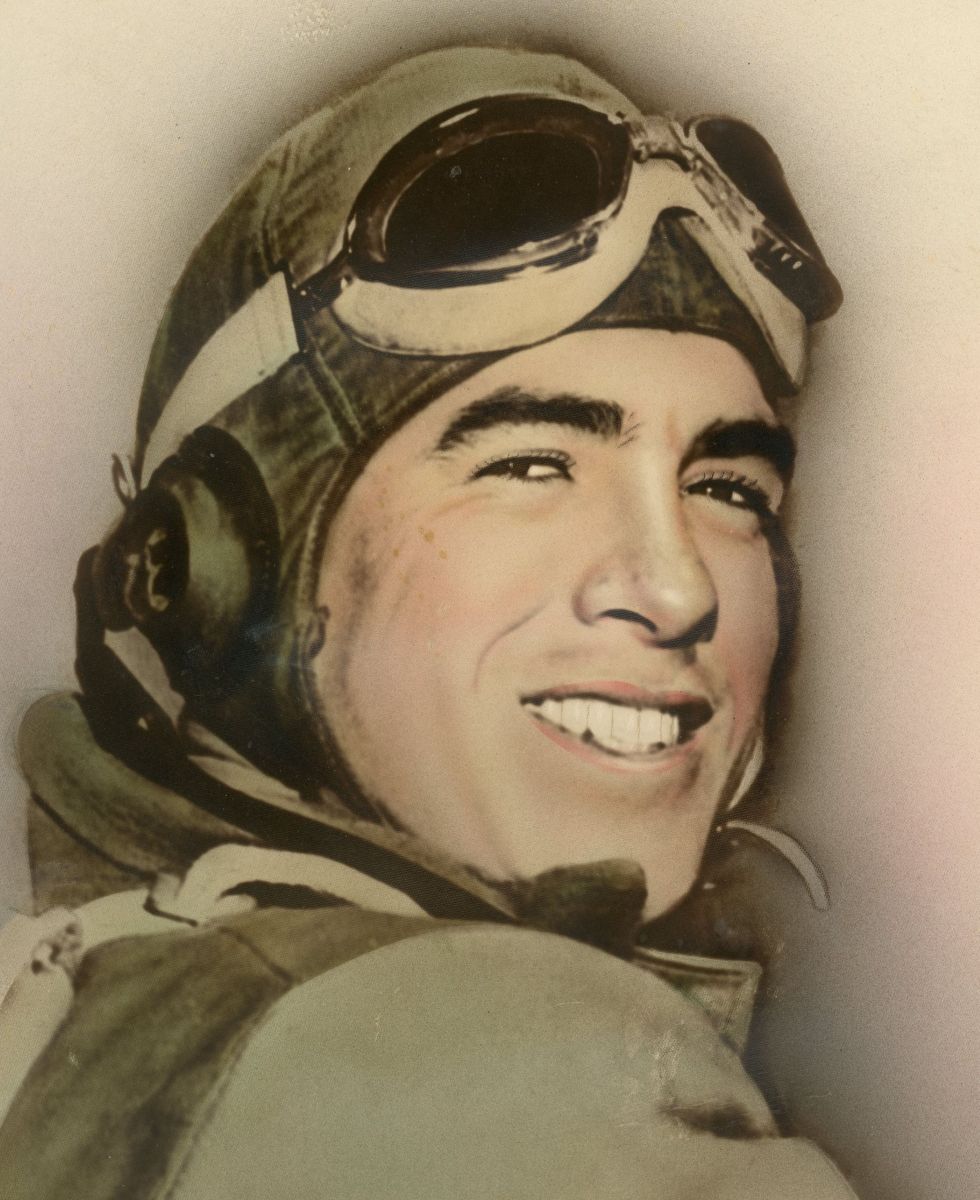

The SBD Dauntless, known today as Midway Madness, was built as an SBD-2 variant at the Douglas Aircraft plant in El Segundo, California, as construction number 632 and was issued the Bureau Number 2106. On December 28, 1940, the aircraft left the factory and arrived at the coast in San Diego two days later, on December 30. On New Year’s Eve, 1940, at Naval Air Station San Diego (now NAS North Island), BuNo 2106 was formally assigned to Bombing Squadron 2 (VB-2) stationed aboard the carrier USS Lexington (CV-2). While flying with VB-2, BuNo 2106 was given the fuselage code “2B2” and still had the distinctive yellow wings of prewar US Navy aircraft and was often flown by Lt. junior grade Mark T. Whittier, originally from Rice Lake, Wisconsin. Through the early half of 1941, SBD-2 BuNo 2106 was at sea along with the “Lady Lex,” and in July 1941, the SBDs of the Navy and the Marines were ordered to be repainted in an overall Non Specular Gray/Light Gray scheme, as although the U.S. was still officially neutral during WWII, many in Washington could see that the war fought in Europe and Asia could escalate, and so the bright prewar colors were over sprayed for what became known as Neutrality Gray. One month later, in August 1941, VB-2 received orders to fly to Lake Charles, Louisiana, to participate in the U.S. Army’s Louisiana Maneuvers. Conditions in Louisiana were rough, with the planes slogging through ankle-deep mud and operating from runways consisting of crushed rock. The solid rubber tailwheels used on the Dauntlesses for carrier operations now found themselves mired in the Louisiana mud, resulting in a shipment of air-filled tires taken from the Douglas production line for A-24 Banshees, the Army’s version of the SBD, but when the mud dried to dust, the Wright R-1820 engines ingested so much dust into the oil coolers and other engine components that all of VB-2’s SBDs were fitted with replacement engines after they were flown back to San Diego.

By the autumn of 1941, tensions were escalating in the Pacific between Japan and the United States, and as a result, two of the three aircraft carriers in the US Navy’s Pacific Fleet (USS Lexington and USS Enterprise) were called upon to deliver Marine fighter and dive bomber (aka Scout Bomber) aircraft to Midway Island and Wake Island. While USS Enterprise was delivering Grumman F4F Wildcats to Marine Fighting Squadron 211 (VMF-211) on Wake Island, USS Lexington was to bring Vought SB2U Vindicators of Marine Scout Bombing Squadron 231 (VMSB-231) to Midway Island. In order to transport the Vindicators, some of the ship’s Dauntlesses, including BuNo 2106, were left behind at Naval Air Station Ford Island, right in the middle of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, where they would soon be in the center of Day of Infamy. On December 7, 1941, Japanese carrier-borne fighters and bombers launched a devastating surprise attack on the U.S. installations in and around Pearl Harbor. The scene on Ford Island consisted of horrified American sailors, soldiers, and airmen watching as the battleships moored on the island’s south side suffered heavy damage from bombs and torpedoes, with the USS Arizona erupting in a massive explosion, the USS Oklahoma capsizing, and the aircraft parked on the flight aprons and the seaplane ramps being bombed and strafed. While two of Lexington’s SBD-2s left on Ford Island were destroyed in the Japanese attack, SBD-2 BuNo 2106 survived, thanks to the fact that it was tucked away in a hangar that was not struck during the attack. When the Lexington received the news of the attack, some 500 nautical miles southeast of Midway, the ship cancelled its ferry mission, and its planes went on patrol for the Japanese carrier fleet until they were forced to return to Pearl on December 13 after exhausting their onboard supplies.

With SBD-2 BuNo 2106 back aboard Lexington, it went with the ship on raids against Japanese bases across the Pacific, all the while receiving armored seats and a bulletproof windscreen while at sea, along with a new overall blue paint scheme. On March 10, 1942, the aircraft was part of the raid on the Japanese anchorages at Lae and Salamaua, New Guinea, where Lt. Mark T. Whittier flew his familiar mount from the Gulf of Papua, over the Owen Stanley Mountains alongside other aircraft from USS Lexington, namely F4F Wildcats of VF-2, Douglas TBD Devastator torpedo bombers of VT-2, and fellow SBDs of VB-2 and VS-2. During the raid, Lt. Whittier and his rear gunner, Aviation Radioman Second Class Forest G. Stanley, dove upon what they believed to be a Japanese cruiser or destroyer.

Whittier would later describe this scene in a postwar interview: “The stinging bite of high altitude, cold air now became hot and tropically humid; I’d better release – punch ‘the pickle’ on the stick, 1000 pounds drop off, and I heave back, tighten gut muscles, yell to keep blood in the head, no blackout on this ride; close the dive flaps – close – close! They wouldn’t! Windshield, goggles, and hood all steamed over from the rapid temperature change. Close those flaps! No, something is wrong! Instead of enjoying a nice 200-250 knots for a hasty retreat, I was having to apply more and more power just to maintain 100 knots! Altitude 500 feet and just able to hold it. What’s wrong? AA? Run out of Fuel? Cannibals? Water landing? All flashed through my mind. Then I began to simmer down. ‘Don’t let this plane fly you, Whittier,’ I’d said many times. Now what could be wrong? The dive brakes open hydraulically, so do the wheels and engine flaps; maybe system pressure from the prolonged dive airlocked the plumbing; try lowering the gear. Here I am over enemy territory with wheels down, dive flaps open at 100 knots! Wheels up again. Try the flaps once more, AND THEY CLOSED! The speed shot up, and I began to climb.” Whittier did not look back to see the result of his dive bombing, and instead, he and his gunner, Forest Stanley, made an uneventful return flight to the USS Lexington. Upon debriefing, Whittier’s fellow pilots reported that his bomb had struck the aft section of his target, and they saw the ship’s stern briefly rise out of the water from the force of the explosion. While one SBD-2 of Scouting Squadron 2 (VS-2) was shot down, the initial American reports claimed 12 ships sunk, the Japanese would claim that while three transport ships and one minesweeper were sunk, they would report that the warships at Lae and Salamaua were only lightly damaged. Nevertheless, Lt. Mark Whittier would be awarded the Navy Cross and Radioman Second Class Forest Stanley the Distinguished Flying Cross for their actions in SBD-2 BuNo 2106.

When USS Lexington returned to Pearl Harbor on March 26, SBD-2 BuNo 2106 was one of several aircraft offloaded from the ship at Pearl, which then sailed out for what would be its final patrol, as when the Lady Lex fought in the Battle of Coral Sea on May 8, 1942, the ship was struck by two bombs and two torpedoes by Japanese carrier aircraft, resulting in the eventual scuttling of the ship after its crew was evacuated from the listing ship. In the meantime, SBD-2 BuNo 2106 was officially transferred to the Pearl Harbor Aircraft Battle Force Pool on April 15, 1942, to be overhauled and kept in reserve to replenish other squadrons. On May 6, BuNo 2106 was assigned to Carrier Aircraft Service Unit 1 (CASU-1), which then sent the aircraft to Bombing Squadron 3 (VB-3), which had served on the Lexington’s sister ship, USS Saratoga. The Saratoga, however, had been torpedoed by the Japanese submarine I-6 on January 11, 1942, and VB-3 had been disembarked at Pearl Harbor while the Saratoga set off for lengthy repairs at Bremerton, Washington. Just nine days later, though, SBD-2 BuNo 2106 was transferred again to the Aircraft Battle Force Pool to await transfer to a new squadron. On May 23, the aircraft was assigned to the 2nd Marine Air Wing at Pearl Harbor, and was one of several SBD-2s transported by aircraft transport ship USS Kitty Hawk (APV-1) to Midway Atoll to join the newly-formed Marine Scout Bombing Squadron 241 (VMSB-241), which was made up of obsolete SB2U-3 Vindicator dive bombers now mixed with the newly-arrived Dauntlesses, while the primary Marine fighter squadron on Midway, VMF-221, was a mix of Brewster F2A-3 Buffalos and Grumman F4F-3 Wildcats.

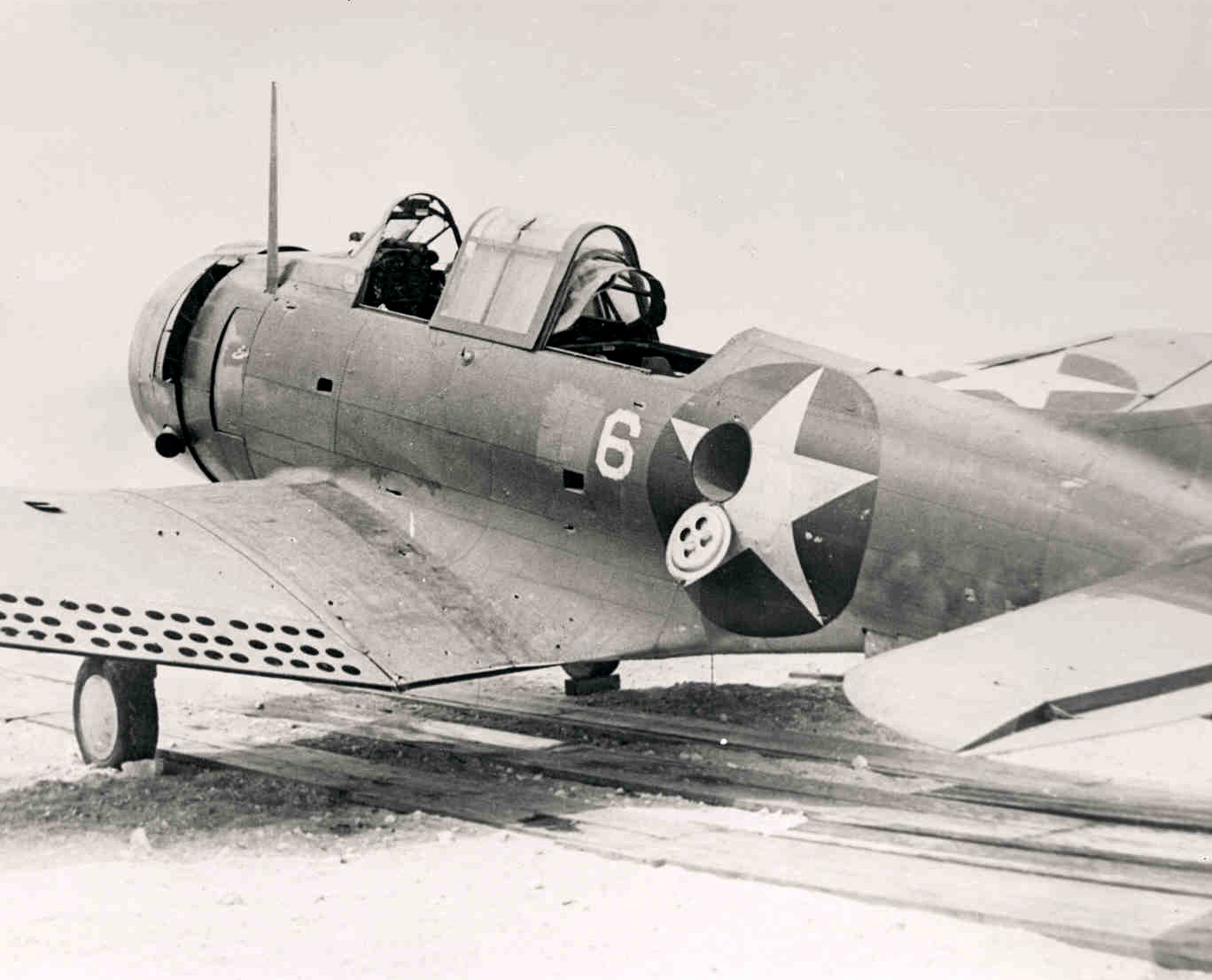

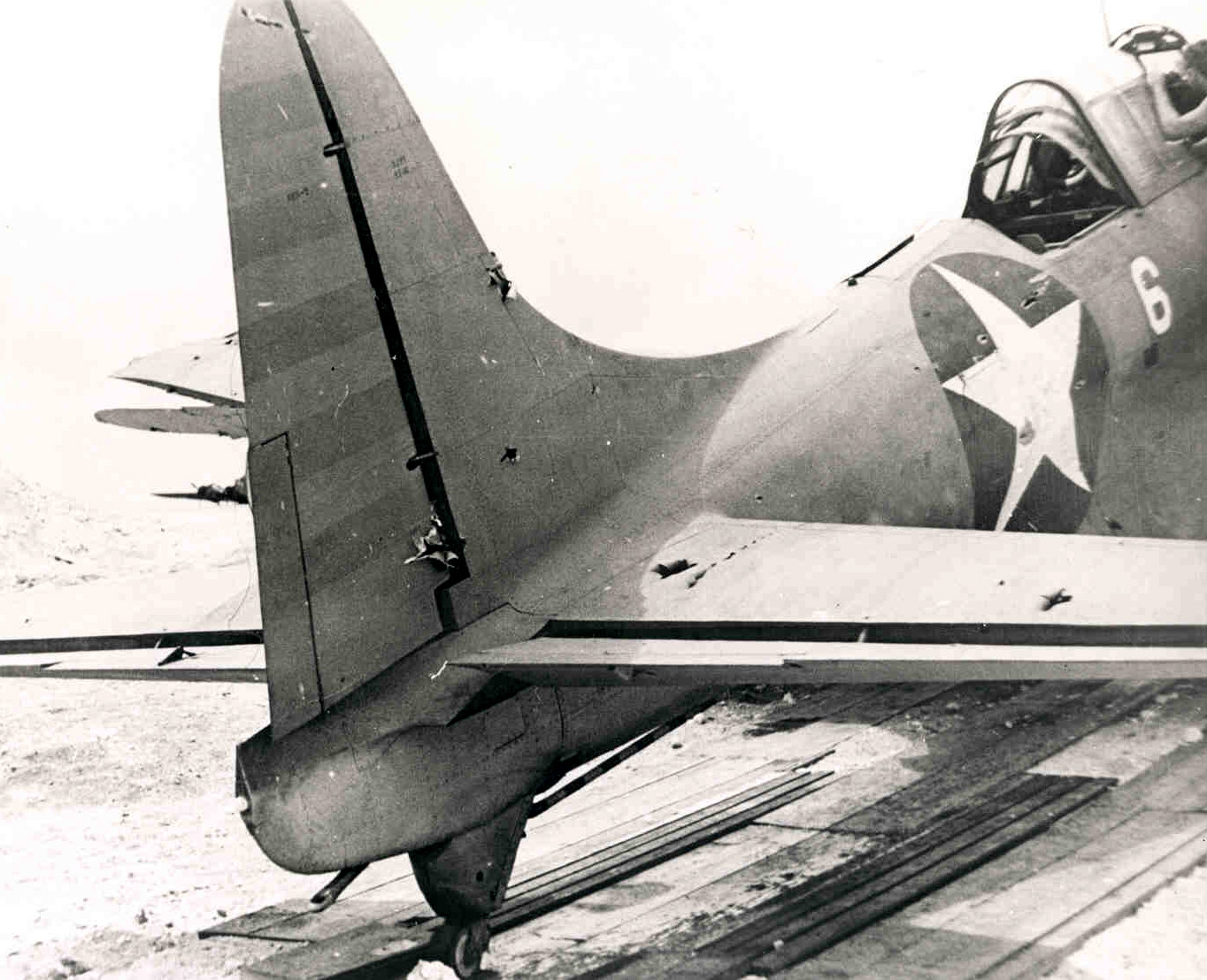

The Marine aviators on Midway had been rushed through training to hold the line at Midway, and were forced to defend the island with worn-out airframes, but they were determined to do whatever it took to keep Midway in American hands as they were reinforced by a detachment from USS Hornet’s Torpedo Squadron 8 (VT-8) armed with the brand-new Grumman TBF-1 Avenger, Consolidated PBY Catalina patrol flying boats, and by Boeing B-17E Flying Fortresses and Martin B-26 Marauders of the U.S. Army Air Force. Meanwhile, the Japanese, unaware that American codebreakers had deciphered their codes, sailed for Midway, thinking they would lure the last American aircraft carriers in the Pacific into an advantageous position, not knowing that the carriers were already on their way. June 4, 1942, would become the most pivotal day of the battle, but while the Japanese attacked Midway Island, the USAAF, USN, and USMC air groups all converged on the Japanese carrier fleet, led by four of the six carriers that had attacked Pearl Harbor. But for the Marine aviators of Midway, the eventual victory over the Japanese would exert a heavy toll on the men and machines of VMF-221 and VMSB-241. VMF-221’s Buffalos and Wildcats fought the Japanese Zeros, “Kates”, and “Vals” over Midway, and VMSB-241’s Vindicators and Dauntlesses attacked the carrier fleet. Of the 25 fighters of VMF-221 scrambled from Midway, only 10 returned, and of those, only 2 were still flyable, as the rest were so badly damaged from Japanese gunfire. Of VMSB-241’s 16 SBD-2s and 11 SB2U-3s, only 8 SBD-2s and 5 SB2U-3s returned, and among the airmen lost was VMSB-241’s commanding officer, Major Lofton Henderson, for whom Henderson Field on the island of Guadalcanal was later named.

Flying SBD-2 BuNo 2106, coded fuselage no. 6, during the Battle of Midway were pilot First Lieutenant Daniel Iverson, a pastor’s son from Miami, Florida, and gunner Private First Class Wallace J. Reid, born in Oklahoma but raised in Washington state. Following the attacks by the US Navy SBD-3 Dauntlesses of USS Yorktown and USS Enterprise that crippled and ultimately sank the carriers Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu, and the counterattack from the carrier Hiryu that crippled USS Yorktown, Iverson and Reid and their fellow Marine aviators joined the Navy aviators of Enterprise, Hornet, and aviators from the crippled Yorktown that had refueled and rearmed on Yorktown’s two sister ships. Lt. Iverson would describe the battle as follows: “From the time we began our approach, I observed fighters taking off the deck(s) of the enemy carriers … I observed Major Henderson [the squadron commanding officer] being attacked by enemy fighters … while approaching the target, but [he] kept the squadron intact until his plane seemed to go out of control about 2,000 feet. I selected a carrier target and peeled off through a thin cloud.

“The carrier I hit was one of three that I saw … My bomb, according to what I observed and my rear seat man said, hit just astern of the deck, a very close miss. “After observing my bomb explosion … I threaded away from the fleet on a course of 240 degrees. Two other fighters joined the fighters already pursuing me. The fighters pursued me, making overhead runs for twenty or thirty miles, when I was able to gain altitude and get into the clouds … My plane was hit several times … My throat [mic] cord was severed by a bullet, and my hydraulic system was shot away … [I] had to land with one wheel up. My left wing was damaged in landing. “On the enemy carrier, I observed almost an entire ring of fire from the flight deck. The fire appeared to be coming from the batteries of three-inch and machine guns.”

During the escape from the Hiryu, P1C Reid was wounded in his foot by the Japanese Zeros, and when Iverson made his one-wheel landing back on Midway, SBD-2 BuNo 2106 had over 200 bullet holes. Yet Lt. Iverson and Private Reid were among the lucky ones, and even flew the following day, on June 5, when the remains of VMSB-241 participated in the attack on the Japanese cruiser Mogami and Mikuma, the latter of which would be sunk on June 6. For their actions on June 4, 1942, Lt. Daniel Iverson was awarded the Navy Cross, and Private 1st Class Wallace Reid the Distinguished Flying Cross, respectively.

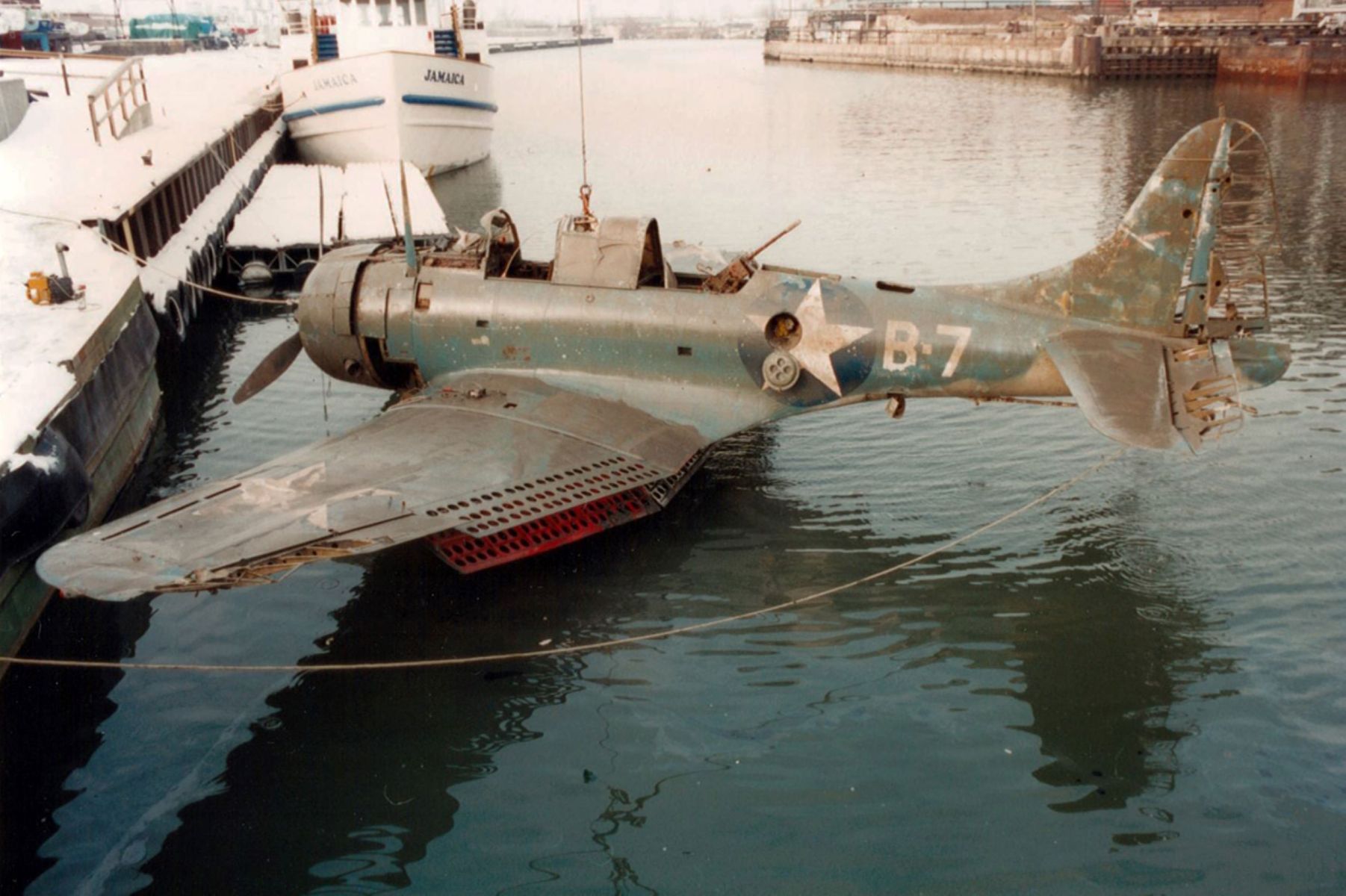

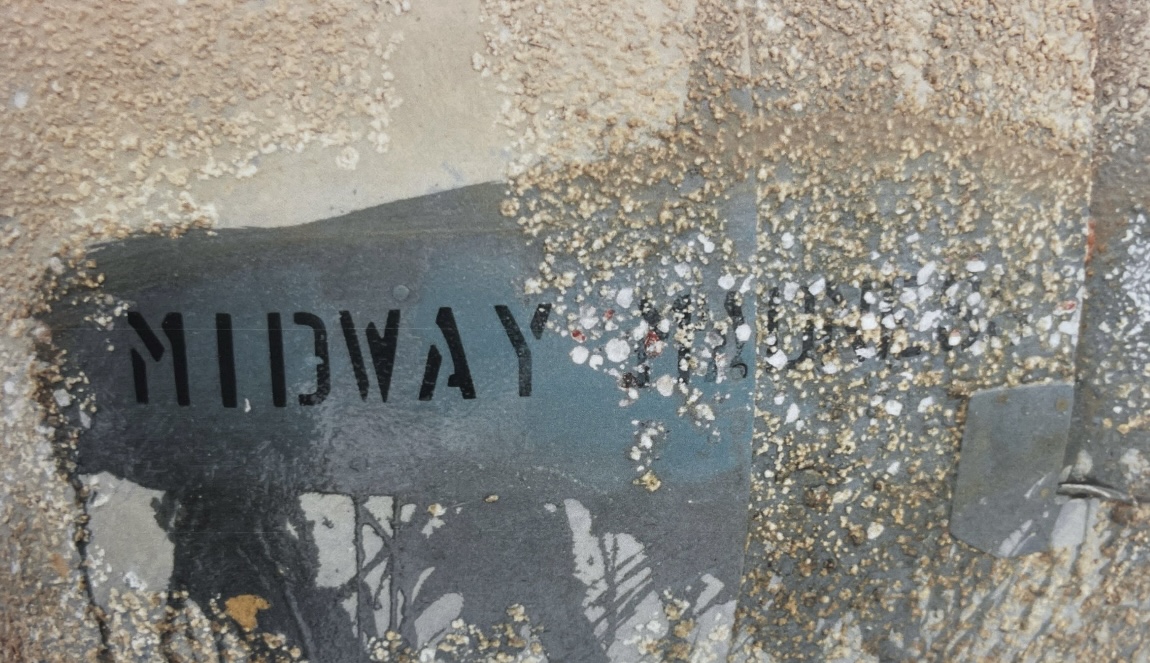

By this point, though, SBD-2 BuNo 2106 was deemed no longer capable of operating in combat. Like many war-weary aircraft, it would be shipped back to the continental United States to be used in training operations in order to give new Navy and Marine aviators experience on the types of aircraft they would fly overseas. On June 21, 1942, BuNo 2106 left Midway and returned to Pearl Harbor for the final time on July 3, where on July 5, it departed for San Diego, arriving there on July 22, 1942. For the remainder of 1942, SBD-2 BuNo 2106 would remain in San Diego before being shipped out on January 18, 1943, to Naval Air Station Glenview, just north of Chicago, and assigned to the Carrier Qualification Training Unit (CQTU). The CQTU used the converted paddlewheel excursion liners USS Wolverine (IX-64) and USS Sable (IX-81) as training carriers on Lake Michigan. The aircraft’s recent combat record at Midway had not been forgotten, as it would be given the name “Midway Madness,” which was stenciled on the aircraft’s engine cowling. The aircraft was also issued the fuselage code B-7.

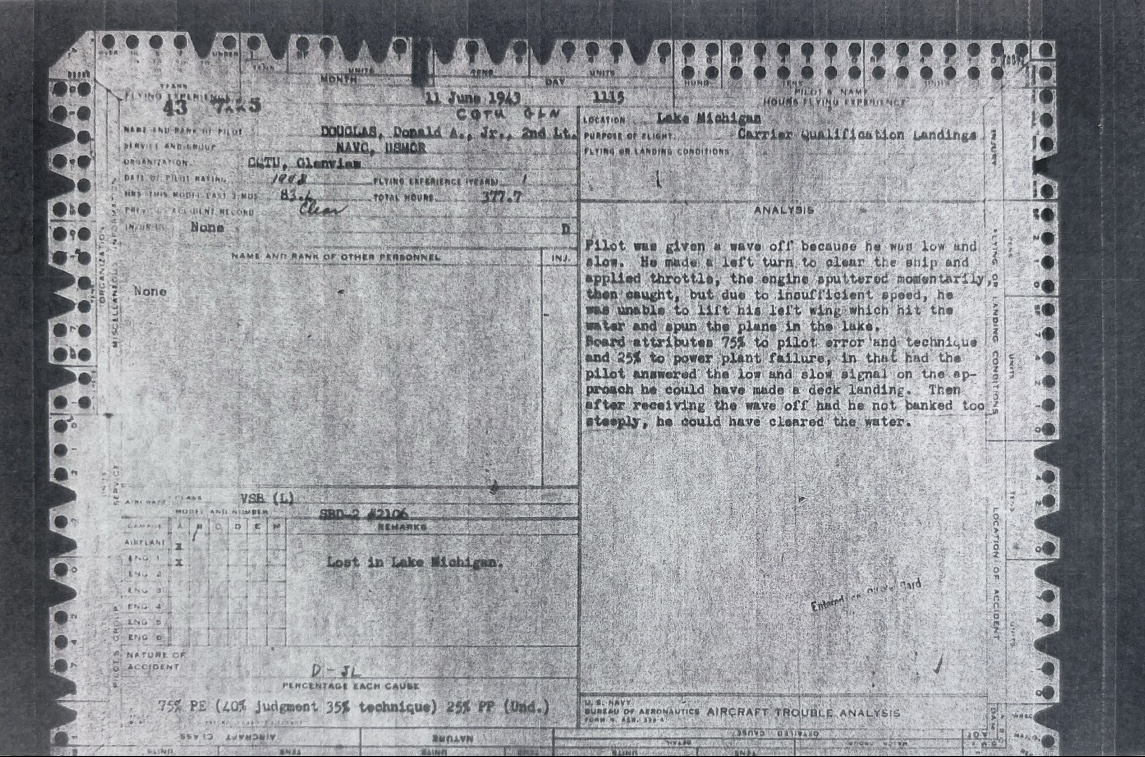

On June 11, 1943, SBD-2 BuNo 2106’s luck finally ran out on what was meant to be another routine training flight. At the controls was Lt. Donald A. Douglas, Jr., US Marine Corps Reserves (no relation to the founder of Douglas Aircraft). While on an approach to land on the flight deck of USS Sable, the ship’s Landing Signal Officer (LSO) instructed Douglas to wave-off because he was flying too low and too slow. As Douglas made a left turn and applied his throttle to avoid the Sable, the engine on BuNo 2106 sputtered momentarily, and because the aircraft was already too slow, the left wing made contact with the surface of the lake, pulling the rest of the aircraft in. Lt. Douglas was rescued from the aircraft, but the SBD-2 “Midway Madness” sank to the bottom of Lake Michigan, one of the many US Navy aircraft lost in flight training operations on Lake Michigan.

50 years after SBD-2 BuNo 2106 was lost to the depths of Lake Michigan, local divers Allan Olson and Taras Lyssenko began scouring the bottom of Lake Michigan and recovering the wrecks of WWII aircraft, eventually securing contracts from the National Naval Aviation Museum to recover the aircraft lost serving in the CQTU under the organization A & T Recovery. On October 18, 1993, Lyssenko and Olson dove on SBD-2 BuNo 2106 and confirmed its identity by noting the Bureau Number stenciled on the tail, still clearly visible after 50 years underwater. Three months later, Douglas SBD-2 Dauntless BuNo 2106 “Midway Madness” was raised from the lakebed on January 13, 1994, and placed upon a dock, being on dry land for the first time in half a century. Soon, the outer wing panels and the rear gun were removed from the aircraft, and the wings and fuselage were loaded onto a flatbed trailer and driven down to the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida, to undergo restoration. The restoration of “Midway Madness” would take seven years, but in 2001, the restoration was completed, and Douglas SBD-2 Dauntless BuNo 2106, the last surviving airplane to have fought in the Battle of Midway, was placed on public display in the NNAM’s West Wing.

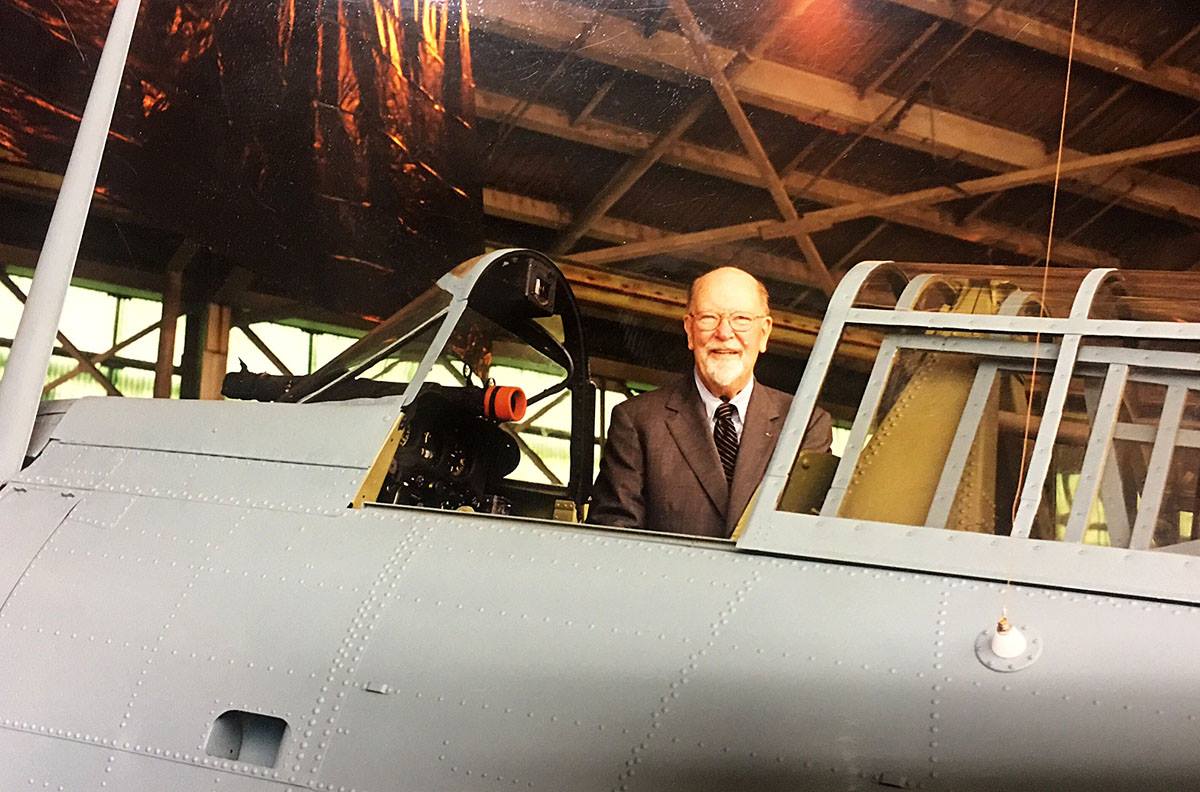

At the time that SBD-2 BuNo 2106 was at last placed on display, only one of the four servicemen to have flown on the aircraft in combat survived to see the Dauntless again. This was Mark T. Whittier, who remained in the US Navy after WWII and retired in 1969 with the rank of Captain, and was honored to once again sit in the cockpit of the restored aircraft. Unfortunately, Whittier’s former gunner, Forest Glen Stanley, was later lost at sea near Guadalcanal on November 14, 1942, after being transferred to the USS Enterprise.

As for the crew of BuNo 2106 during the Battle of Midway, Daniel Iverson would serve at Guadalcanal, and after being wounded, he was rotated back to the continental United States, where he would be reassigned as a flight instructor at NAS Vero Beach, Florida, and promoted to the rank of Major. Sadly, on January 22, 1944, Major Iverson was killed during a mid-air collision with another aircraft over Vero Beach. Gunner Wallace J. Reid would also serve at Guadalcanal, earning the Silver Star and the Air Medal, and would survive the Second World War, and was subsequently commissioned as a Second Lieutenant upon graduating from Officer Candidate School. On the outbreak of the Korean War, 2nd Lt. Reid was deployed with the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade to guard the Pusan Perimeter but was killed in action on August 8, 1950. When the SBD-2 they had flown at Midway was placed on display, members of Iverson and Reid’s families were in attendance for the ceremonies. Meanwhile, Captain Mark Whittier would donate his Navy Cross to the National Naval Aviation Museum.

Today, Douglas SBD-2 Dauntless BuNo 2106 “Midway Madness” stands proudly on display in Pensacola, still bearing the metal patches placed over the bullet holes from its days in combat. While it is faithfully repainted in the colors it wore on Midway with VMSB-241, right down to the overpainted red and white stripes on the fabric-covered rudder as seen in the historic photos taken after its return to Midway, two panels on the tail of the aircraft remain “unrestored” to show the original WWII paint of the aircraft, and a portion of the pre-war yellow wings it wore with USS Lexington is still visible on the leading edge of the wing root on the right wing of the aircraft. All of these help this historic aircraft continue to tell the inspiring stories of the Navy and Marine aviators who flew SBD-2 BuNo 2106 into combat and will be an everlasting reminder of the Battle of Midway for generations to come.

Special thanks to Richard K. Wills, author of the memo Dauntless In Peace and War: A Preliminary Archaeological and Historical Documentation of Douglas SBD-2 Dauntless BuNo 2106 Midway Madness, which goes into detail about the service history of SBD-2 BuNo 2106 and the findings made on the aircraft when it was recovered from Lake Michigan. Links to the memo found HERE and HERE. For more information, visit the National Naval Aviation Museum’s website HERE.

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.