In the early years of the twentieth century, Italy had no tradition of air combat, as aviation was still new. It was still closer to sport than to war, and when Italy entered World War I in May 1915, its air arm was small and poorly equipped. However, despite limited resources, one name, Francesco Baracca, defined Italian fighter aviation during the war. Baracca was born in a well-off family on May 9, 1888, in Lugo di Romagna. From 1907 to 1909, he attended the Military Academy of Modena and then the Cavalry Training School. On July 15, 1910, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 2nd Cavalry Regiment, Piemonte Reale, based in Rome. Like many young officers of his class, he enjoyed the social life that came with the uniform. There were concerts, dinners, opera evenings, hunting parties, and frequent correspondence with friends and admirers. That sense of style never left him, and it would later shape his “airman’s way of life.”

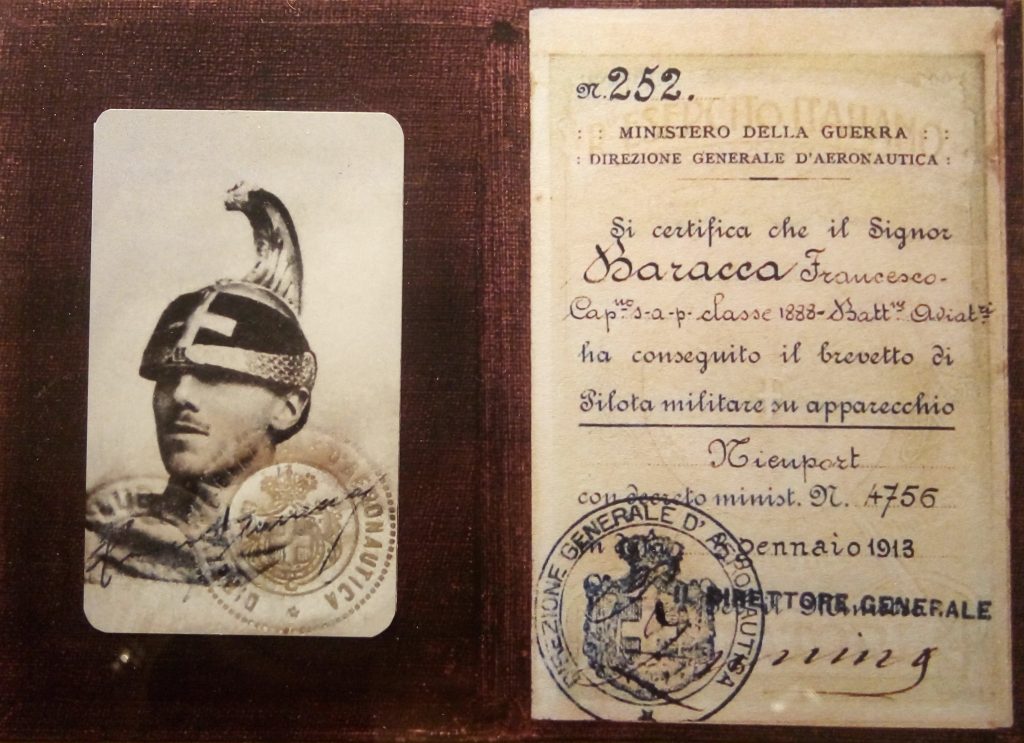

In April 1912, Baracca went to Reims in France to attend a flying school. He earned his pilot’s license there and wrote long letters home describing the excitement of flight, the discipline among pilots, and the feeling of rising above the ground. He returned to Italy in July 1912 and was assigned to the flying detachments. When Italy prepared to enter the war in 1915, its aviation arm was still weak, and in the spring of that year, the army purchased Nieuport aircraft from France. On May 23, 1915, the day before Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary, Baracca arrived in Paris for further training. He flew near the front and saw the trenches from the air for the first time. He witnessed aerial encounters and understood quickly that air fighting would become more than reconnaissance. He wrote home with enthusiasm, but also with surprise at the scale of modern war.

Francesco Baracca: Italy’s First Ace

Upon returning to Italy, Baracca was part of the units flying Nieuports. The initial months were frustrating because Italian machine guns were prone to jamming, causing Austrian aircraft to intercept. Air combat was still new, and hence, pilots were experimenting with tactics, often learning by trial and error. On April 7, 1916, Baracca achieved his first confirmed victory. It had taken time and patience, but he had proven himself. Over the next few months, he gained thirty-three more victories. On February 11, 1917, his fifth victory was confirmed. That made him the first Italian “ace,” the first to reach five confirmed kills. From that moment, his name began to circulate not just within his squadron but across the country. Italy needed heroes, and Baracca fit the image. On March 20, 1917, he began flying the SPAD S.VII, which was equipped with a synchronized machine gun firing through the propeller arc. Later, he flew the more powerful SPAD S.XIII.

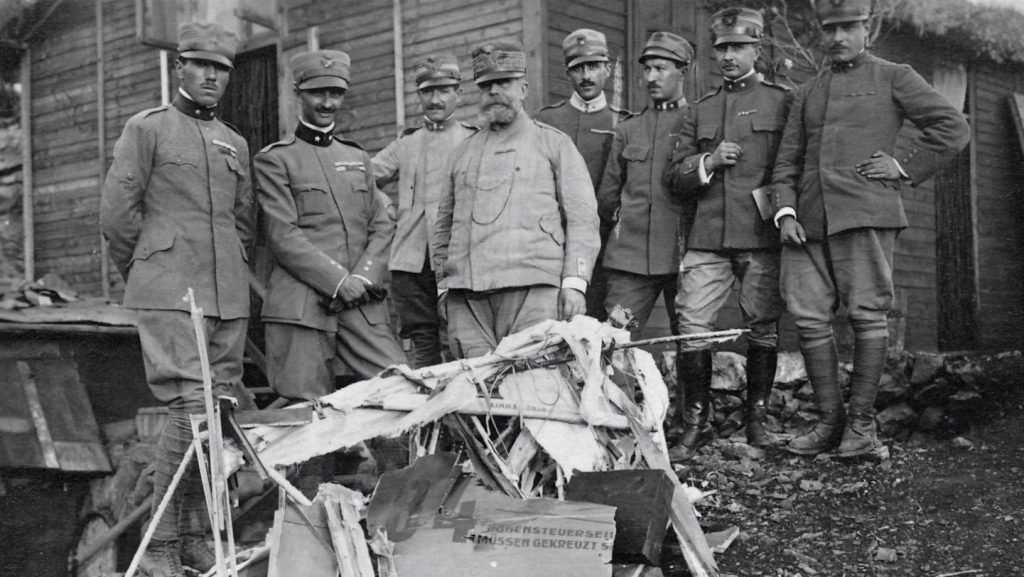

On June 6, 1917, he was appointed commander of the 91st Fighter Squadron, a unit that would become one of Italy’s most respected formations. By September 6, 1917, after his 19th victory, he was promoted to major for war merit. He had already received multiple decorations for bravery. On October 24, 1917, Austria-Hungary and Germany launched the offensive that led to the Italian defeat at Caporetto. The army retreated under heavy pressure. It was one of the darkest moments of the war for Italy. In the forty days that followed, Baracca shot down 10 more enemy aircraft. While the army struggled on the ground, he maintained a steady pace in the air. By this stage, he had become not only a successful fighter pilot but a symbol of resilience. In total, Francesco Baracca was credited with 34 aerial victories. He fought along multiple fronts between Italy and Austria-Hungary, often at high altitude over the mountains, where weather and terrain added to the danger. His personal emblem was a black prancing horse, which he painted on his aircraft. It was derived from the insignia of his former cavalry regiment. The symbol would later gain a life far beyond aviation.

The Last Flight

In mid-June 1918, the Austrians launched their final offensive along the Piave River, and fighting intensified again. On June 19, 1918, at about 6 p.m., Baracca took off on a ground-attack mission, flying low to strafe enemy infantry with his machine gun. A few minutes later, his aircraft crashed on the Montello hill near Nervesa when he was just 30 years old. Italian authorities stated that he had been killed by ground fire from an infantry machine gun, while Austrian sources credited his death to Arnold Barwig, an observer in a Phönix C.I aircraft. Baracca’s death caused a strong reaction across Italy, and the authorities could not recover his body before May 23. He had already become a public figure, and his loss was felt both at the front and at home. He was posthumously awarded Italy’s highest decorations for valor. In the years that followed, his name became part of Italy’s aviation identity.

During the 1920s, a young racing driver named Enzo Ferrari received permission from Baracca’s family to use his prancing horse emblem on his cars. The symbol, originally painted on a fighter aircraft, would later become known around the world. Today, Lugo di Romagna hosts a museum dedicated to him. His letters are preserved in archives in Milan and Lugo, offering a personal record of a man who began as a cavalry officer and became Italy’s most celebrated ace. Baracca’s story goes far beyond his 34 victories, as he became an ace when air combat was very new to Italy, and pilots were still struggling with it. He provided an image to all Italian fighter pilots, and like other aces of World War I, his bravery continues to inspire even today.

Related Articles

Kapil is a journalist with nearly a decade of experience. Reported across a wide range of beats with a particular focus on air warfare and military affairs, his work is shaped by a deep interest in twentieth‑century conflict, from both World Wars through the Cold War and Vietnam, as well as the ways these histories inform contemporary security and technology.