By Randy Malmstrom

Since his childhood, Randy Malmstrom has had a passion for aviation history and historic military aircraft in particular. He has a particular penchant for documenting specific airframes with a highly detailed series of walk-around images and an in-depth exploration of their history, which have proved to be popular with many of those who have seen them, and we thought our readers would be equally fascinated too. This installment of Randy’s Warbird Profiles takes a look at the Evergreen Aviation and Space Museum’s de Havilland DH-4M-1 (Airco DH-4M-1), Construction Number ET4.

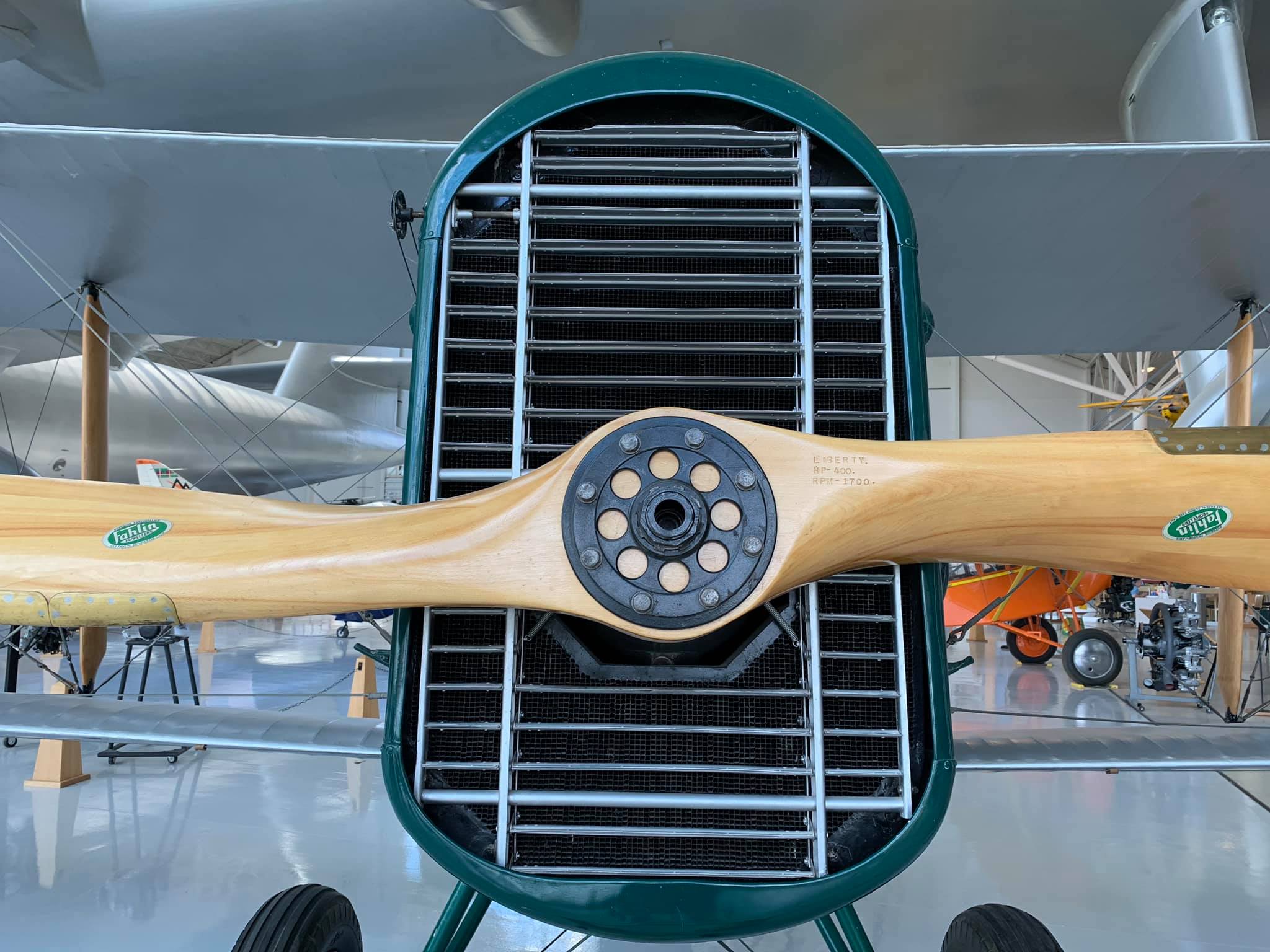

This particular aircraft is a rare example of the DH-4M-1 (M for modernized) built under license by Boeing Aircraft Company in 1918; it did not see combat in World War I but rather, was one of 180 de Havilland DH-4’s modified by Boeing in 1923 as a single-seat civilian variant for use by the U.S. Post Office Department. The original DH-4 tandem seat design was modified so that the flight controls were in the rear cockpit and the forward cockpit was replaced by a watertight compartment for mail delivery. From what I have seen, this was part of the collection of famed stunt pilot Paul Mantz. My photos at Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum in McMinnville, Oregon.

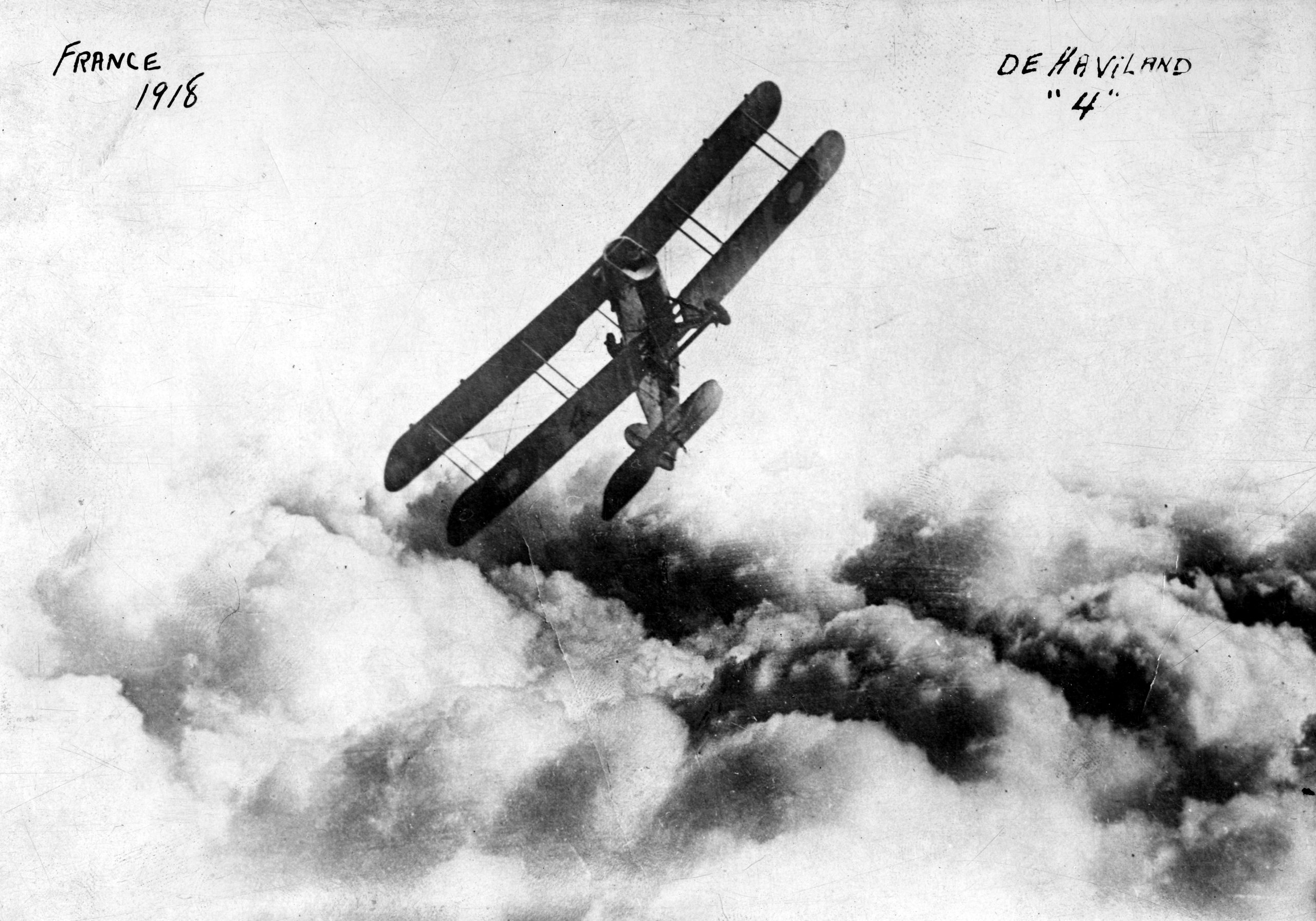

This is by no means intended to be a comprehensive history of the DH-4 aircraft. The DH-4 was a two-seat biplane designed as an observation and daylight bomber of World War I, designed in 1916 by Aircraft Manufacturing Company Limited (Airco) chief designer Geoffrey de Havilland (hence the “DH” designation) and built initially by Airco, although production was subcontracted out during the war. The DH-4 was notable for being the first purpose-built two-seat daylight bomber for the British Royal Flying Corps, but became a multi-purpose aircraft including reconnaissance, long-range fighter sweeps, air ambulance and anti-submarine patrols. It first flew in August 1916 and entered service with the Royal Flying Corps No. 55 Squadron on March 6, 1917. No. 2 Squadron of the Royal Naval Air Service received delivery of the D.H.4 in March-April 1917. Over 6,000 were produced in the U.K. alone.

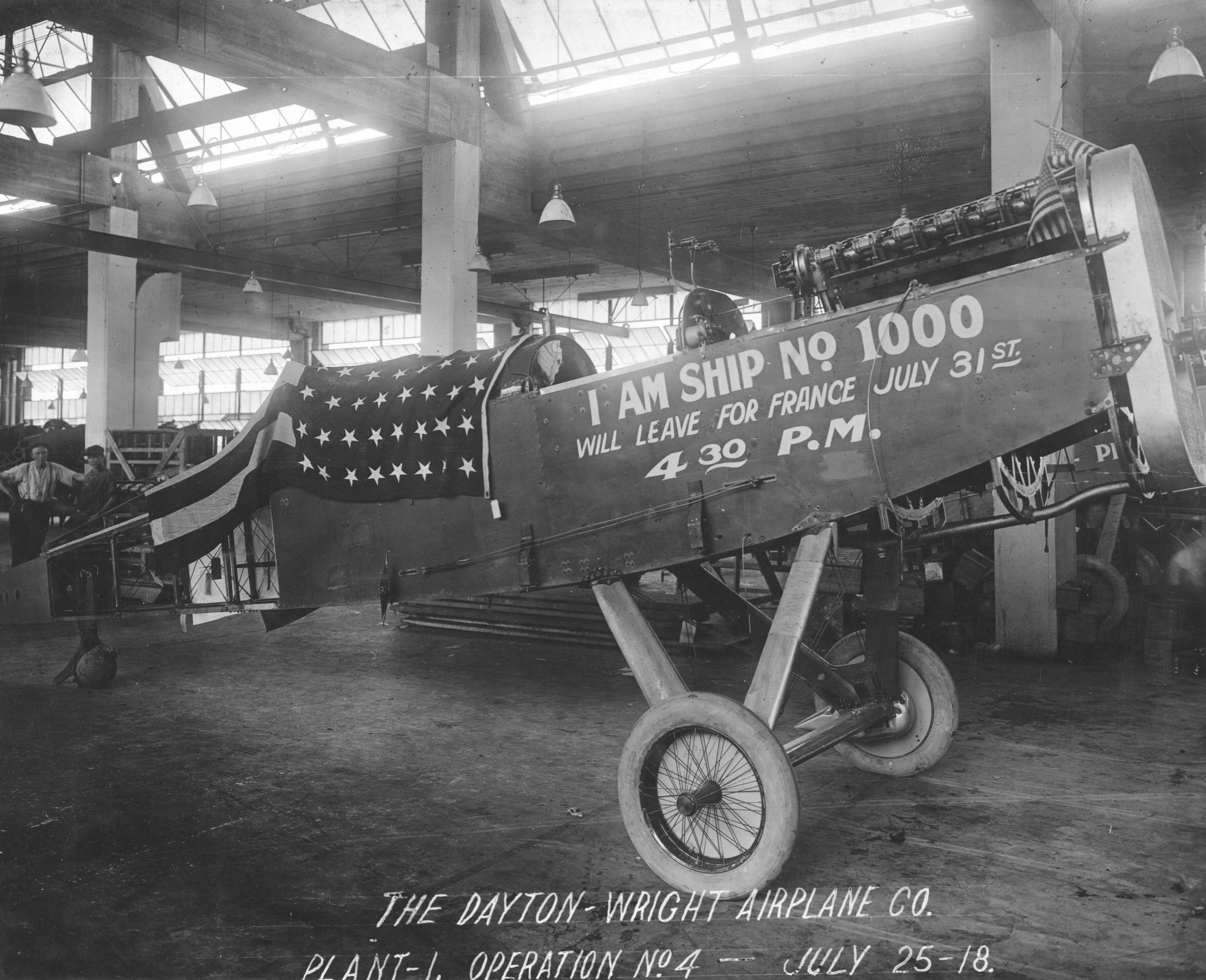

When the U.S. entered the war in April 1917, the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps did not have any combat-worthy aircraft, so what became known as the Bolling Commission was established under the direction of Colonel R.C. Bolling which studied several European aircraft, including the French SPAD XIII, the Italian Caproni bomber, British SE-5, Bristol Fighter, and DH-4, with the idea of arranging for their manufacture in the U.S. The DH-4 was selected because of it seemed well-suited to the new American 400-horsepower Liberty L-12 engine (after initial technical problems encountered with the L-12 prototype, which had designed and built in only six weeks, where resolved). comparatively simple construction, and its apparent adaptability to mass production; yet even so, changes from the original British design were required to apply U.S. mass production methods (exactly what those are, I do not know). In the end, nearly 5,000 DH-4’s were built under license in the U.S. as a general-purpose two-seater aircraft for service with the United States Army Air Service in France and were nicknamed “Liberty Planes” with Dayton-Wright Company of Dayton, Ohio being the largest U.S. producer.

Fisher Body Division of General Motors Corporation of Cleveland, Ohio produced 1,600 aircraft, and the Standard Aircraft Corporation of Patterson, New Jersey, built 140 machines, and there were orders to build an additional 7,502 aircraft which were cancelled after the armistice. The aircraft-grade lumber for those aircraft was supplied by the Spruce Production Division’s Spruce Cut-Up Mill at Vancouver Barracks, Vancouver, Washington (Pearson Airfield). The U.S.-built aircraft first arrived on the Western Front in May 1918 but were not initially combat ready and, requiring further preparation, the first U.S. combat mission in the DH-4 was with the 135th Aero Squadron on August 2, 1918. By war’s end, 1,213 DH-4s had been delivered to France.

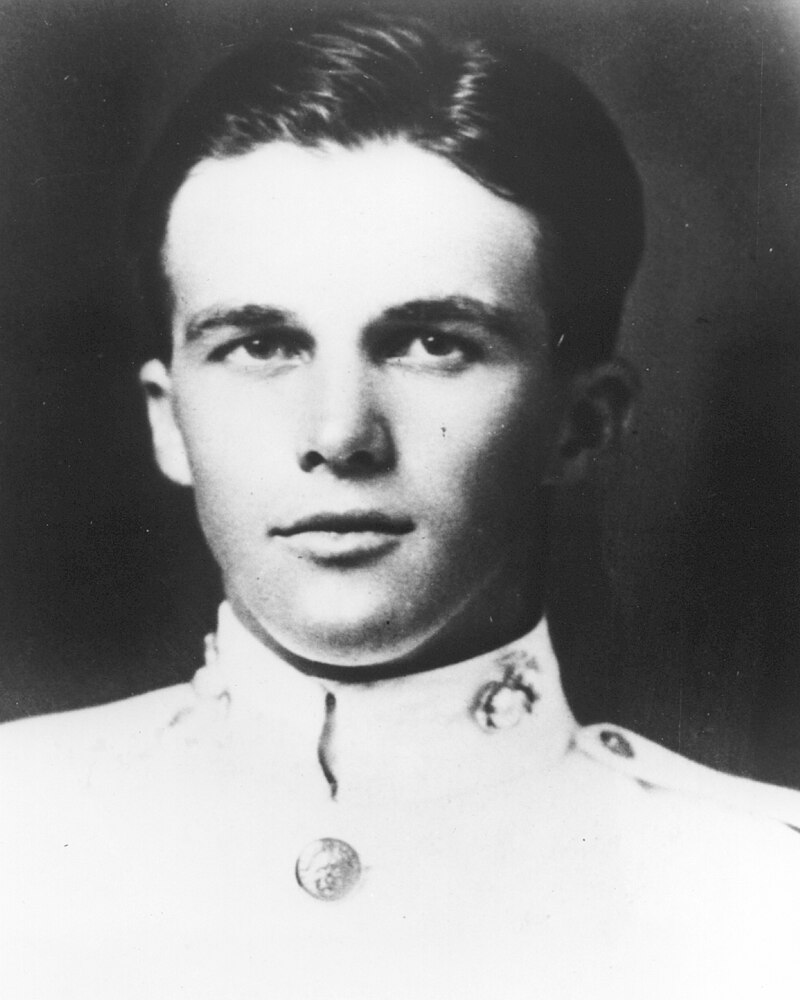

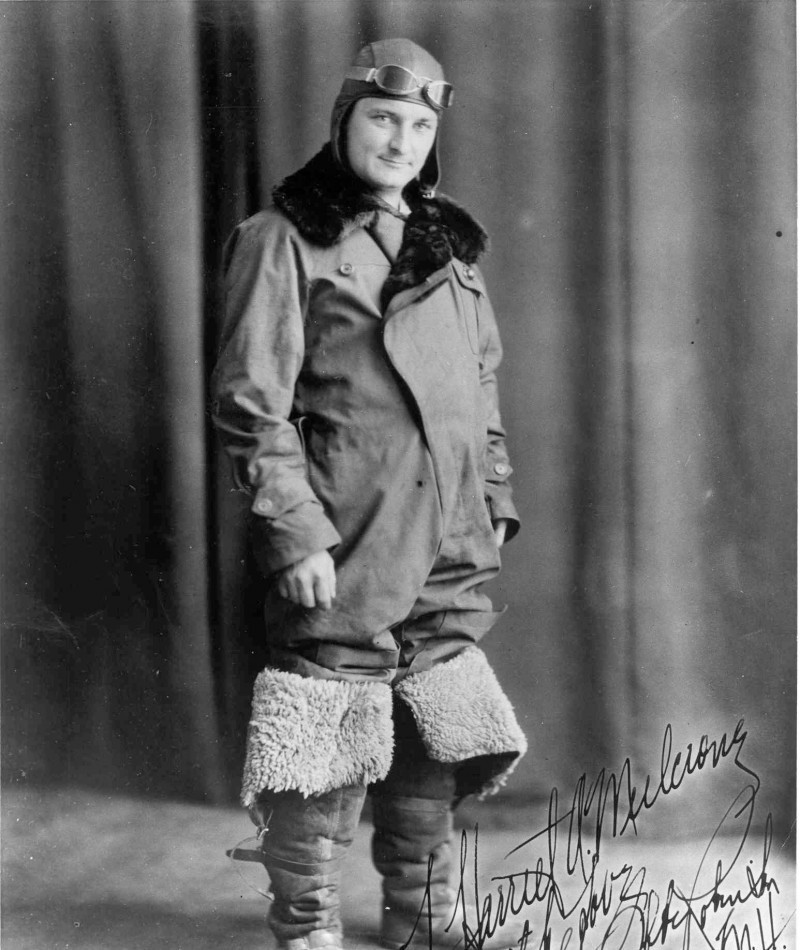

They were the only American-made warplane to see combat in World War I, and although they were in combat for less than four months before war’s end, of the six U.S. Medal of Honor recipients to aviators during the war, four were received by pilots and observers flying DH-4s – two of them were given posthumously to Lt. Harold Goettler and 2nd Lt. Erwin Bleckley of the 50th Aero Squadron who, on October 8, 1918 flew repeated missions over enemy lines to drop supplies to the survivors of the 77th Division (which became known as the “Lost Battalion”), performing the first successful American combat airlift operation. The other DH-4 recipients being 2nd Lt. Ralph Talbot and Gunnery Sgt. Robert Robinson of Squadron C, 1st Marine Aviation Force, Marine Day Bombing Wing, USN Aviation Force Northern Bombing Group, Foreign Service in France (the WWII-era Bagley-class destroyer USS Ralph Talbot (DD-390) was named after Talbot, this first U.S. Marine aviator to receive the Medal of Honor). Armament consisted of one or two fixed, forward-facing .30 caliber Lewis machine guns synchronized to fire through the propeller arc with a mechanical interrupter gear and two .30 cal. machine guns in a movable, rear-facing Scarff twin-mount fired by the gunner/observer.

The DH-4 built by Westland to British Admiralty specifications had twin guns forward and aft and with the higher-mounted Scarff ring. The Scarff ring was designed by Warrant Officer (Gunner) F. W. Scarff of the Admiralty Air Department. The main undercarriage had bungee cord (shock cord) suspension (bungee” or “bungie” is thought to be British slang for India-produced rubber). Powerplant: the British-built aircraft had Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines, and the U.S. built aircraft had a Liberty L-12 400 hp. engine. The large main fuel tank was fitted between the pilot and observer/gunner and hindered communication and a speaking tube was used. Payload: 460 lbs. of bombs on undercarriage and/or under-wing racks (only 332 lbs. of bombs on the U.S. built with the Liberty engines).

The DH-4 was nicknamed the “Flaming Coffin” for its somewhat undeserved reputation to catch fire, and crews of the British Royal Flying Corps tended to be fond of the aircraft and once also an American service during WWI, there were only 8 fatalities resulting from accidents. The actual reason for the nickname had to do with the location of the fuel tank – between the pilot and the rear gunner – (which changed on the US version). What could happen is the weight of the fuel in the tank would cause it to carry forward under momentum as the aircraft came to an abrupt stop in a forced landing or crash, thus it could break loose from its mountings and pin the pilot between the fuel tank and the engine, and it the fuel tank ruptured, it might possibly spill fuel onto the hot engine and cause a fire, which could incinerate the pilot.

Nonetheless, when the aircraft were decommissioned in January 1919 and converted for the U.S. Post Office Department, the cockpits were repositioned in the rear of the plane behind the fuel tank and they were padded against rough landing; the fuselage was then constructed of plywood sheets over wooden struts instead of the original linen sheeting (the compass, air pressure gauge, and altimeter were redesigned for more accurate readings. The DH-4B variant for U.S. postal service placed the sole flight controls in the aft cockpit and did away with the forward cockpit and replaced it with a watertight mail compartment. It became known as the “Workhorse of the Airmail Service” and in the first year along, DH-4Bs carried over 775 million letters.

Variants of the DH-4 remained in civilian service for airmail, crop-dusting, forestry patrol and survey work into the 1930’s by companies in various countries around the globe. Between February 22–24, 1921, 2nd Lt. William D. Coney (Air Service, United States Army) flew a DH-4 across the North American continent with just a single fuel stop, flying between San Diego and Jacksonville, Florida in 36 hrs. 27 min. As an aside, the Kelly Act of 1925 authorized the U.S. Post Office to contract with private mail carriers on designated routes, and the Post Office announced a competition for a replacement to these converted military de Havilland D.H.4 aircraft that were flown for air mail since 1918. And so, the McNary-Watres Act of 1930 (The Airmail Act of 1930) awarded airmail contracts to three major airlines: Boeing Air Transport (which later became United Airlines), Transcontinental Air Transport (which later became TWA upon its merger with Western Air), and Robertson Aircraft Corporation (which later became American Airlines).

About the author

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.