By Randy Malmstrom

Since his childhood, Randy Malmstrom has had a passion for aviation history and historic military aircraft in particular. He has a particular penchant for documenting specific airframes with a highly detailed series of walk-around images and an in-depth exploration of their history, which have proved to be popular with many of those who have seen them, and we thought our readers would be equally fascinated too. This installment of Randy’s Warbird Profiles takes a look at the Polikarpov I-16 Type 24, s/n 2421014, N7458, maintained in airworthy condition by the Flying Heritage and Combat Armor Museum in Everett, Washington.

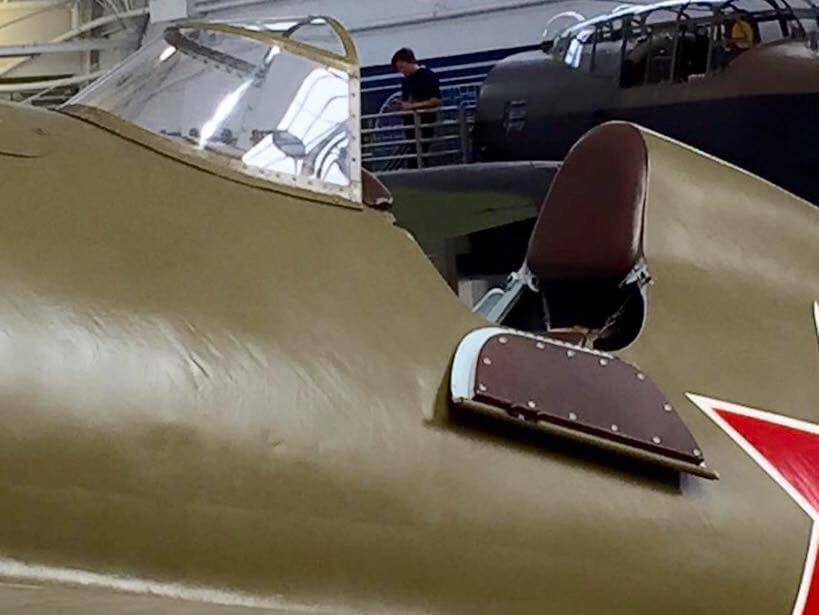

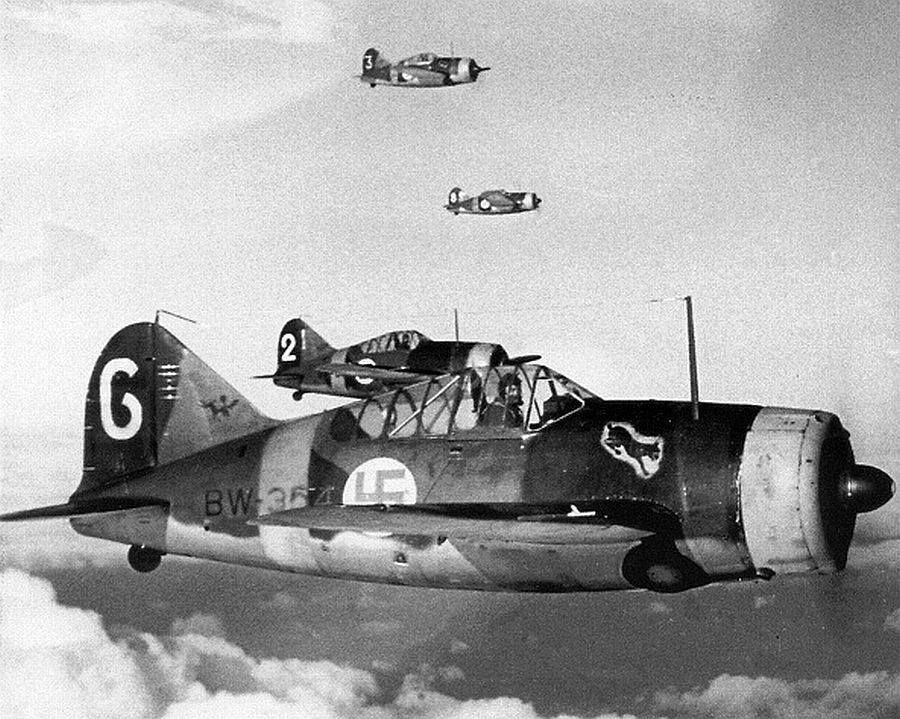

Polikarpov I-16 Type 24, s/n 2421014, N7459. From what I can determine, this particular aircraft was built in 1940 at the Polikarpov Design Bureau Plant No. 21 (a Soviet “OKB” or Experimental Design Bureau) in Nizhny, Novgorod (also known as Aviation Plant 21 and now the location of MiG manufacturing), and from July 10, 1940, it was deployed to the Eastern Front. The exact details are not definitively known from the records I have read, but it may have been one of two Russian I-16’s that were shot down when five B-239 aircraft (see description below) of No. 24 Squadron of the Finnish Air Force including ace Flight Master Yrjö Turkka (who wrote about the incident) encountered them on August 13, 1941, near Soanlahti, Finland (a former municipality of Karelia), which flew up to intercept Soviet bombers.

To provide some context, in 1939, following requests by the Finnish Embassy in Washington, D.C., a total of forty-four U.S. Brewster F2A-1 “Buffalo” aircraft that were originally intended for the U.S. Navy were diverted at the behest of the U.S. State Department to Finland for use by the Finnish Air Force (FAF) and designated by Brewster as the Model B-239E. They were flown at first during the Winter War of 1939-40 between the Soviet Union and Finland. There they were never referred to as the “Buffalo” by the FAF, but merely “Brewster” or by nicknames such as “Sky Pearl” and “Pearl of the Northern Skies” and “Butt-Walter” (or “Pylly-Walter,” the significance of which I have not found) and “American Hardware” (American metal) and “Flying Beer Bottle,” and they received FAF serial numbers BW-351 though BW-394 (“BW” aircraft).

What lends some credence to Turkka’s story is the fact that this aircraft was rediscovered in 1991 at Lake Yaglyayarvi in Karelia. Sir Tim Wallis and his chief engineer Ray Mulqueen of the Alpine Fighter Collection of Wanaka, New Zealand, had discovered a total of nine aircraft wrecks including three I-153 aircraft, and contracted with the Aeronautical Research Bureau of Novosibirsk to remanufacture six examples of the I-16. This was the fifth I-16 to be restored and (with this aircraft at least) at the same factory where the I-16s were originally manufactured and two of the restorers had been young workers at the plant in 1941 while the I-16s were still being produced. It was flight tested and certified in Russia before being disassembled and sent to New Zealand and flew at the 1998 Warbirds over Wanaka Air Show. Also in 1998, it was acquired by Paul Allen to later be owned by his Vulcan Warbirds Inc. (that was incorporated in 2004) for display at his Flying Heritage & Combat Armor Museum (FHCAM) as part of a 4-aircraft deal with the Alpine Deer Group that included the Hurricane Mk. XIIA, Bf-109E-3 and Spitfire Mk.Vc. It has been flown by Carter Teeters if not others at FHCAM. It is painted with board number (tactical or aircraft number) Red 4, similar to one captured at Kaunas, Lithuania. My photos at FHCAM.

This is by no means an attempt to describe the entire history of the I-16. The designation “I” for the Russian transliteration “Istrebitel” for destroyer or fighter. Design work began in 1932 and the TsKB-12 prototype took its first flight on December 31, 1933. The “TsKB-12” designation was given by the Центральное конструкторское бюро (in Cyrillic), or the transliteration “Tsentral’noye Konstruktorskoye Byuro” (Central Design Bureau). Ultimately, its nicknames became the “Rata” (a rat) as referred to by Spanish Nationalists who flew against it during the Spanish Civil War, or “Mosca” (a fly) as referred to by Spanish Republican forces who flew at least 475 of them after arrangements with Joseph Stalin and receipt of payment in Spanish gold (Russian volunteer pilots came to Spain even before the airplanes had arrived and by late November of 1936, there were 300 Russian pilots flying for the Spanish Republican forces). Also known as “ослик” (Ishak or jackass) or “Yastrebok” (Hawk) by Soviet pilots, “Siipiorava” (flying squirrel) by Finnish forces, “Abu” (gadfly) by Japanese forces, and “Dienstjäger“ (service hunter or fighter) by German forces.

Its design has been declared by some as reminiscent of the Granville Brothers Aircraft “Gee Bee Model R” racing aircraft (and may have been an influence). The Soviet Air Force’s strength was about 1,000 aircraft in 1931, and by 1935, it had increased to around 4,000 aircraft, including the I-16, which, when introduced, with its retractable landing gear and variable-pitch propeller, was 60-75 mph faster than its contemporaries from other countries. The fuselage was primarily built up from glued ply veneer (primarily birch) sheets (known as Sphon) that varied from 4 mm at the nose to 2.5 mm at the tail; the wings had metal ribbing largely covered by fabric.

Originally designed with an enclosed cockpit (such as the Type 10 as flown by the Spanish Republican Air Force), due to the fact that biplane-era pilots were used to open cockpits and the canopy tended to fog over, designers went to an open cockpit design. It first appeared in combat when 475 aircraft were shipped to the Spanish Republican Air Force in November 1936 during the Spanish Civil War, where its 1,800 rounds per minute machine guns, ruggedness, maneuverability, climb, and dive rate came as an asset against its opponents.

The Type 24 was a late variant and had a more powerful engine, a tail wheel instead of a tail skid, and could carry external rockets, bombs, or fuel tanks. The powerplant is a 9-cylinder Shvetsov M-63 engine, although some of the prototypes of the various variants were initially equipped with Shvetsov M-25 or Wright Cyclone F-2 engines (built under license), and some were also fitted with a Hamilton Standard three-blade propeller. There is a Hucks Starter hub or dog on the nose hub, thereby avoiding having the weight of an onboard starter motor and battery (a starter truck was positioned in front of the aircraft). The propeller spinner is covered in a metal shroud, secured with threaded wire, for aerodynamic reasons. The pilot has a spade yoke rather than a stick.

Armed with two 7.62 mm Shpitalny-Komaritski Aviatsionny Skorostrelny (ShKAS) machine guns in the cowling, firing through the propeller arc, and the later variants were aimed by a PAK-1a reflective gunsight (replacing the tubular sight). Two more guns were mounted in the wings that fired outside the propeller arc (beginning with the I-17 variant, two 20 mm ShVAK cannons were fitted in the wings). It could carry 1,800 rounds of total ammunition. Rockets or bombs could be fitted under the wings on hard points. When introduced in 1934, replacing the Polikarpov I-15 biplane with largely the same fuselage, it was the first low-wing cantilever monoplane with retractable main landing gear to become operational.

Similar to the Grumman Duck and Grumman F4F Wildcat, the undercarriage was retracted and lowered by a hand crank in the cockpit (located on the starboard side). However, unlike the Wildcat with its “bicycle chain” mechanism, the I-16 undercarriage was controlled directly with a screw-jack with cables attached to the wheel hubs. It takes 44 hand cranks by the pilot to raise and lower the gear (I am told it is easier than that of the Wildcat). Pilots were provided with wire-cutting shears to sever the cables on landing if the mechanism jammed or if the pilot was incapacitated, leaving the gear to deploy by gravity. The landing gear fairings are hinged. Skis were fitted for winter operations, and in some cases were retractable, pulling up under the cowling.

A fabric-on-metal tail section and lack of trim tabs contributed to its somewhat unstable flight characteristics. The two holes in the top of the fuselage behind the windscreen provide light to see the instrument panel. Because of the limited visibility over the cowling on takeoff and landing, pilots would raise their seats using a handle on the starboard side of the cockpit, and due to the narrowness of the cockpit, they were also known to open the cockpit doors to make room for their shoulders. When the aircraft ran out of ammunition, pilots were also known to use the “Taran” technique (Russian for battering ram) to ram aircraft in mid-air and/or use their propeller to sheer off control surfaces. Hispano-Suiza of Guadalajara (SAF-5), then located on the Mediterranean coast at Alicante, Spain, built 50 I-16 aircraft under license after the Spanish Civil War (the Hispano-Suiza automobile company had previously hired Swiss auto designer Marc Birkigt). Also, prior to World War II, about 200 I-16s were flown by Chinese Nationalist forces against Japan over China and Manchuria (where many aircraft were armed with the new RS-82 rocket).

By Operation Barbarossa beginning in June 1941, the aircraft was outmoded, but about 65% of the Russian fighter force flew the I-16, and in all, more than 8,000 of the various model variants were produced since its introduction (depending on your sources). Spain kept a few of the Type 10 aircraft in service until 1952, and about 1 in 30 of the total aircraft production was a UTI-4 (or I-16 UTI, and “UTI” stood for “Uchebno-Trenirovochniy Istrebitel / Fighter Trainer”) tandem-seat trainer variant, some with fixed landing gear. I have read that in spite of all of its characteristics, its design and flight conditions meant that these aircraft had an average of five hours of flight time.

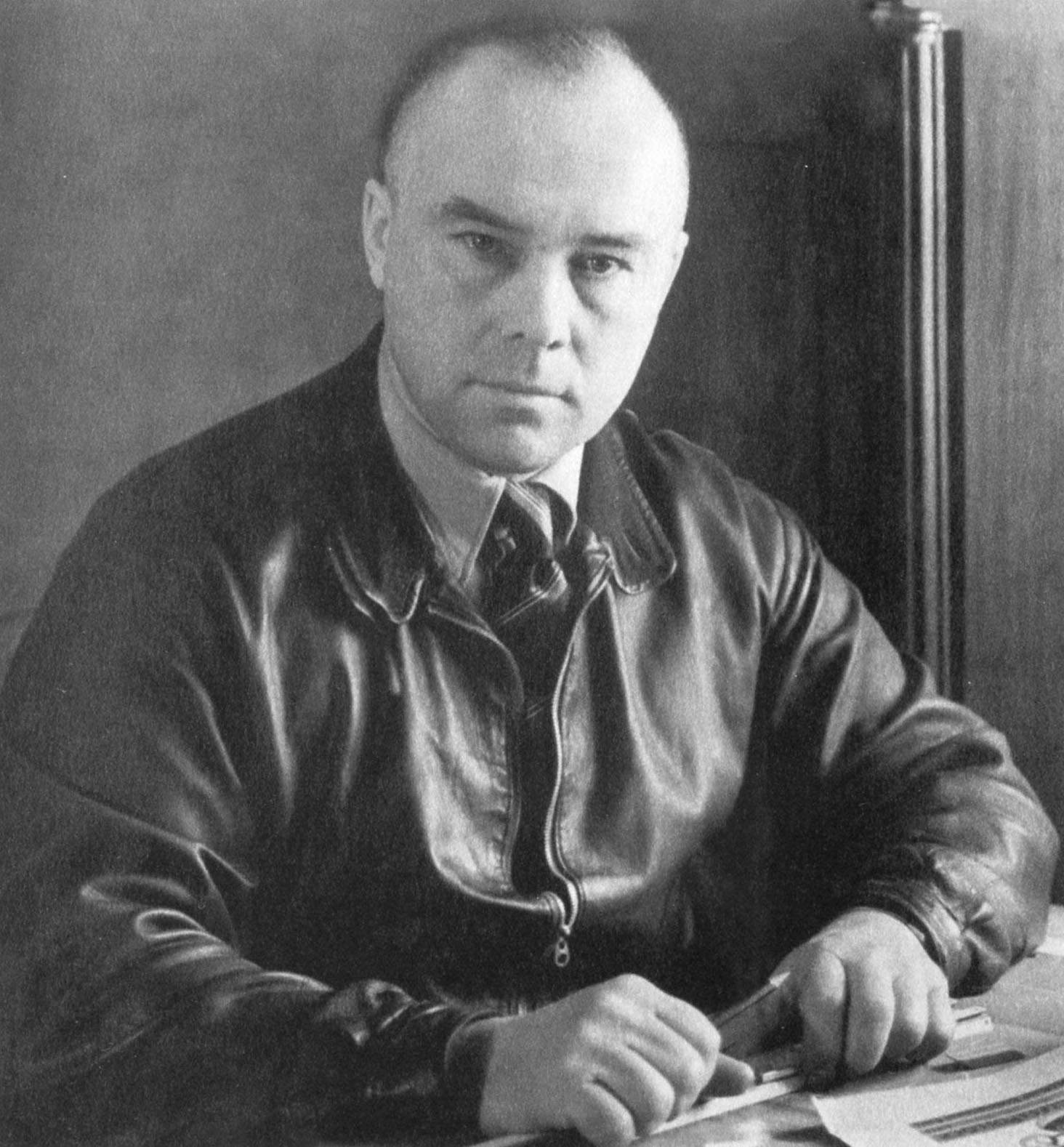

As a result of Soviet purges, designer Nikolai Polikarpov was head of Design Team No. 2 of the Central Design Bureau. He was under “house arrest” at the Central Aerohydrodynamic Institute (Центра́льный аэрогидродинами́ческий институ́т, ЦАГИ (Tsentral’nyy Aerogidrodinamicheskiy Institut, TsAGI)) when the design of the prototype of the I-16 began in 1932. A number of state aircraft factories or design bureau locations were established so that incarcerated aviation designers could work on developing military aircraft, and convict labor could be used to build the aircraft.

About the author

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.