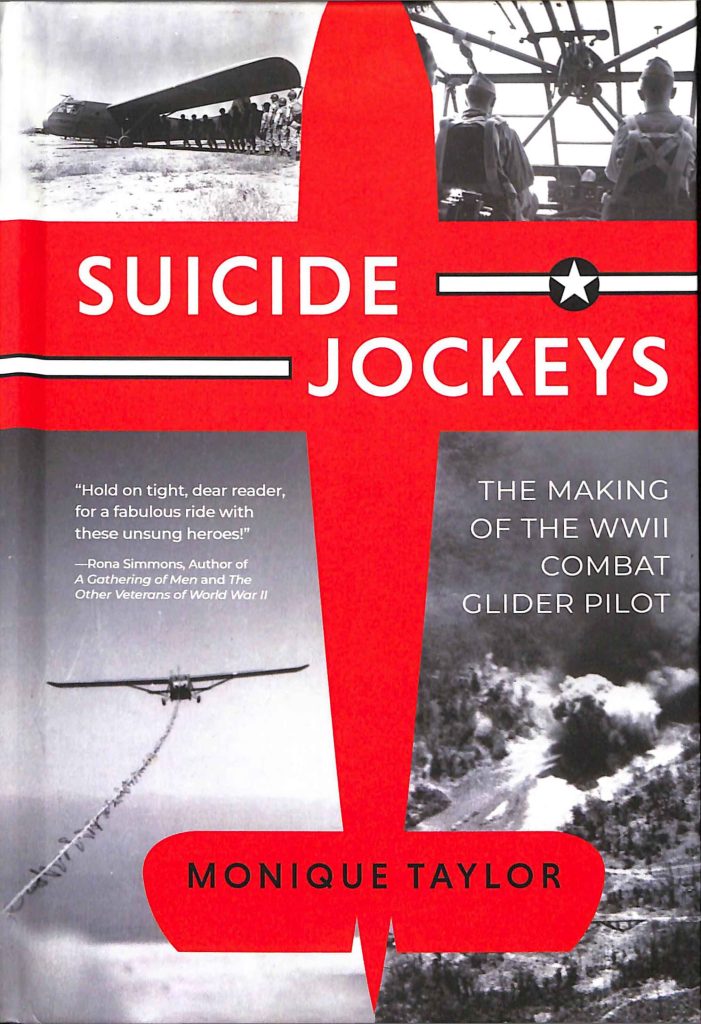

When we mostly read about World War II (WWII) airborne operations, we read in-depth about parachute insertions. We read about the paratroopers with their trials, confusion, derring-do, and initiative. When we read of glider-borne insertions, if we have that opportunity, glider pilots rate hardly a footnote, if any mention at all is ever made of them. This is a great omission in WWII’s written history, given the daring and initiative of glider pilots as well as the logistical importance of delivering arms, cargo, and troops. Monique Taylor’s aim is to correct this injustice, at least from the U.S. Armed Services perspective—and with a unique skill set of being the daughter of a WWII veteran glider pilot, possessing a Master’s degree in history, as well as being an attorney (lawyers know to go beneath the surface of a story).

The story of U.S. glider pilots during WWII is deep indeed. The U.S. glider corps began on the back foot, well after the concept of vertical envelopment began. Imperial Russia and Imperial Germany began using paratroops and glider assault ships shortly after World War I’s conclusion. Later, Great Britain also formed parachute and glider airborne capabilities, while the U.S. continued to lag. As Taylor details, glider corps training in the U.S. began late and proceeded unhurriedly. Taylor illustrates the intrepid nature of glider pilots to overcome a certain lack of resolve by the Army as well as Congress. She also exposes the embarrassing parts, such as the lack of combat training for these pilots. It seems the Army was primarily considering them pilots while not giving them basic infantry training. Landing a one-way ride into a landing zone, invariably within hostile territory to be immediately surrounded by enemy forces (if not immediately fired upon, as what typically occurred with successive waves of gliders) without weapons training, combat assignment, or infantry skills—what could possibly go wrong?

Taylor’s research and interviews uncover how glider pilots overcame these hurdles, usually by being good soldiers—moving to the fight, though their orders were to make their way home (and so landed with minimal gear). She shows how their history is rich with innovation as well as incentive to serve and to win. Taylor also gives the details, both settling and unsettling, of the major glider operations in Europe as well as the major one in Burma. The weight of arms, ammunition, food, fuel, and the number of medical evacuations is eye-watering as these values are incredibly large. Their immense nature underscored the need for gliders as the last link in the logistical supply train for airborne troops to sustain the fight while well within hostile territory.

Glider pilots flew their missions, especially their landings, in unarmored aircraft made solely of tubing and fabric. Often, if fortunate, avoiding obstacles not mentioned, or to be aware of, or planned for in their pre-mission briefings. It was also interesting how the flight crews of the Waco CG-4 gliders made use of the swing-up nose to protect themselves from cargo, such as a Jeep, crashing forward into them after an abrupt stop. Her description of the glider pilot volunteers to relieve the 101st Airborne at Bastogne, during the Battle of the Bulge, as well as evacuate casualties by glider (also interesting to read about), also greatly helps complete the record. Surprisingly, perhaps, Taylor dives into the remark by the commanding general, inferring the glider-borne supply wasn’t required to prevail in the battle. Taylor more than provides evidence that does not support this general’s opinion.

Suicide Jockeys is nicely produced and more than informative. Its images are adequate in quality, though not as extensive as the text. The writing is wonderfully done and reads like a story being told in the family room at home or at the library. Although footnoted expertly and often, there is no index. Suicide Jockeys goes far in uncovering this unjustly ignored facet of the U.S. Army’s glider pilots in WWII. It can serve as an excellent reference, as well as a source of material, on this remarkable and shamefully unheralded aspect of history. Note: it will help to know in the citations that A/B means airborne; GP is used for glider pilot; CP indicates copilot, and F/O means Flight Officer.

| Hardcover Publisher: Köehler Books Year published: 2023 Size: 9” x 6” Index none Bibliography ✔︎ Notes: footnotes Photos: (few) Cost: $24.95 ISBN 979-8-88824-146-2 160 pages Available on Amazon |

Related Articles

I grew up around aviation, with my father serving in U.S. Army Aviation as both fixed- and rotary-wing qualified, specializing in aviation logistics. Life on various Army, Navy, and Air Force bases gave me an early appreciation for aircraft, flight operations, and the people behind them.

Unable to fly for the military, I pursued a career in geology, where I spent three decades managing complex projects and learning the value of planning, economics, and human dynamics. That experience, combined with the logistical insight passed down from my father, shaped my analytical approach to studying aviation history.

After retiring, I devoted my time to exploring aviation’s past—visiting museums, reading extensively, and engaging with authors and professionals. Over the past decade, I’ve written more than 350 book reviews on aviation and military history, still uncovering new stories within this endlessly fascinating field.