By Nicholas Mastrangelo Chief, Technical Publications, Republic Aviation Corporation Originally published in Industrial Aviation, January 1945

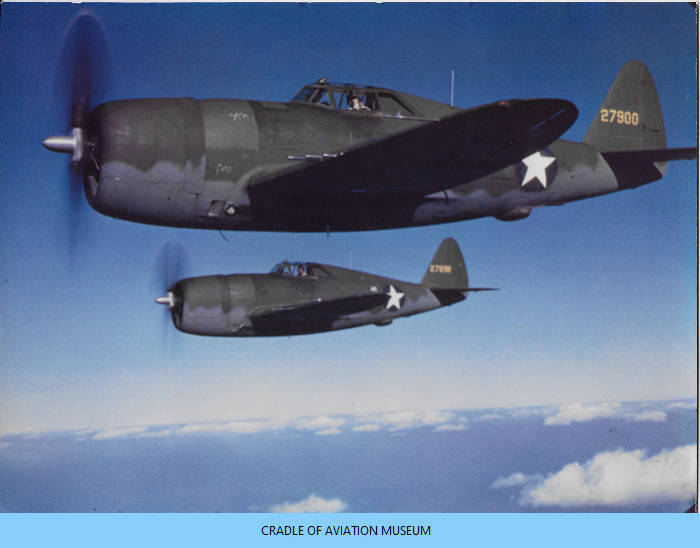

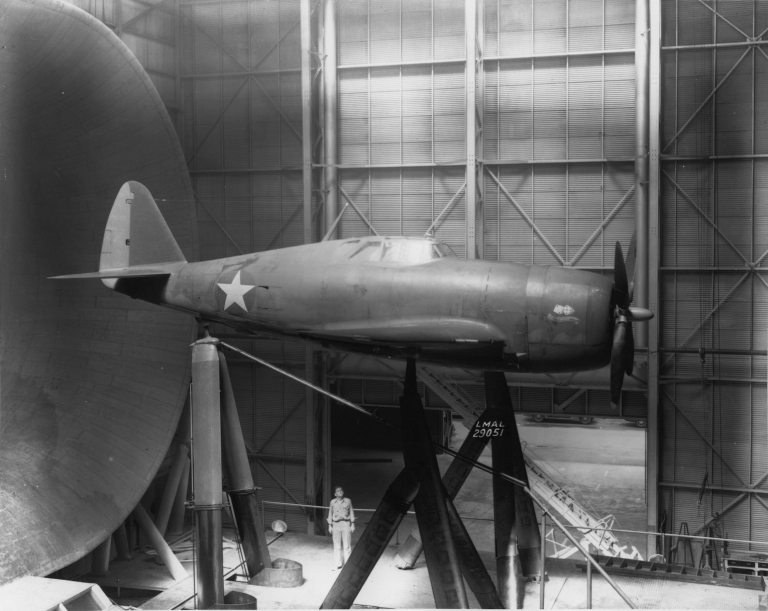

The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt emerged from a design philosophy that sought to extract every possible advantage from contemporary aeronautical knowledge. From its earliest conception, the aircraft was shaped by three core priorities: aerodynamic efficiency, structural strength, and sustained performance at extreme altitude. These objectives drove the adoption of a single-engine, single-fuselage configuration with minimal wing interruption, concentrated mass distribution, and reduced frontal area. Central to the design was Alexander Kartveli’s Republic S-3 airfoil, the product of years of high-speed research, as well as a turbo-supercharging system unprecedented in both scale and complexity. At the heart of the Thunderbolt was the Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp, an 18-cylinder, air-cooled radial engine producing 2,000 horsepower. The requirement to maintain 52 inches of manifold pressure at stratospheric altitudes demanded a supercharging system of exceptional efficiency. Rather than adapting the ducting to a completed airframe, Republic engineers took an unconventional approach: the airflow system was designed first, and the fuselage structure was built around it. The remarkable survivability of combat-damaged Thunderbolts returning with extensive fuselage damage provided compelling evidence that this approach did not compromise structural integrity.

Fuselage Structure

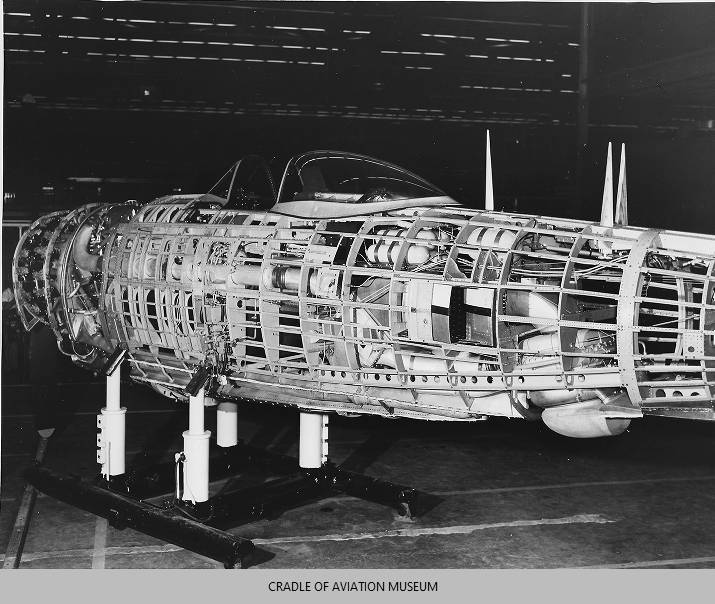

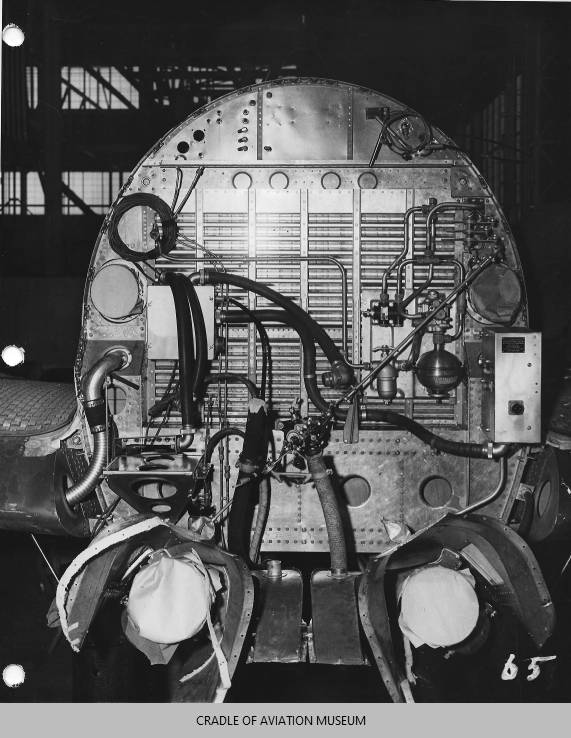

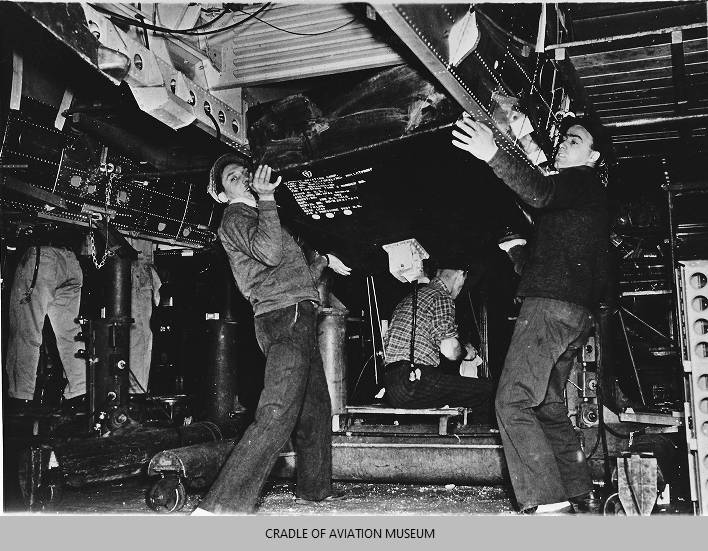

The P-47 fuselage employed an all-metal, semi-monocoque stressed-skin design composed of longitudinal stringers and transverse bulkheads. The forward fuselage was divided into upper and lower halves extending aft to station 302 inches, while the rear fuselage was constructed as a single, self-contained unit. Assembly involved bolting the upper and lower forward sections together along reinforced parting angles, after which the aft section was attached through riveted and bolted frame joints. Structural loads from the wing were carried through two primary fuselage bulkheads located in the lower forward section. Each bulkhead was built around paired steel E-section beams that acted as cross-ties, with forged steel wing hinges secured at their ends. The forward bulkhead doubled as the engine firewall, incorporating stainless steel facing and reinforced alclad sheet, while the aft bulkhead supported the rear wing hinges and mirrored much of the forward structure without the stainless protection.

Lower fuselage longerons extended from trapezoidal forgings at the wing bulkheads and ran the length of the forward fuselage, supporting frames, stringers, and flush-riveted skin panels of varying thickness. Additional reinforcement was provided around wing hinge fittings and other high-stress regions. Although the upper fuselage half was comparatively lighter, it followed similar construction principles and supported cockpit framing, armor plating, and engine mount attachments. The aft fuselage section incorporated fully enclosed frames tied by stringers and was reinforced to withstand tailwheel landing loads. A heavily strengthened frame supported the tailwheel assembly, while transverse webs across the rear frames formed the structural foundation for the empennage.

Wing Design and Construction

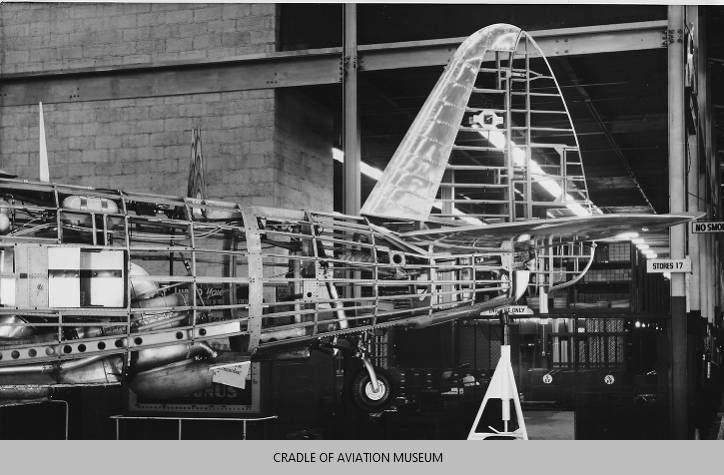

The Thunderbolt’s wing was a full cantilever structure with stressed-skin, multi-cell construction. Spanning 41 feet with a root chord of 109 inches, the wing featured a fixed angle of incidence and dihedral optimized for high-altitude performance. Two primary spars carried the main structural loads, supplemented by auxiliary spars supporting the ailerons, flaps, and landing gear.

Wing skins were butt-fitted and flush-riveted, reinforced internally by extruded angle stringers. Approximately 16 percent of the wing surface consisted of access panels, gear wells, and armament bays, a figure that underscored the inherent rigidity of the primary structure. The main spars used E-section cap strips riveted to webs of varying thickness, with the heaviest material concentrated near the wing root. Wing attachment was accomplished through hinge fittings pinned to corresponding fuselage mounts using tapered bolts and expanding bushings to ensure tight alignment.

Ailerons, Flaps, and Control Surfaces

The P-47’s Frise-type ailerons accounted for just over 11 percent of total wing area and were both aerodynamically and dynamically balanced. Constructed entirely of metal, they were mounted to forged hinges on the auxiliary spar and actuated by push-pull rods. A controllable trim tab was fitted to the left aileron to reduce pilot workload.

Hydraulically operated NACA slotted flaps occupied 13 percent of the wing area. Their complex linkage caused the flaps to move aft before deflecting downward, preserving the wing’s airfoil shape during deployment. Synchronization was achieved through torque tubes and hydraulic pressure, ensuring precise alignment during operation. Later production Thunderbolts incorporated compressibility recovery flaps to aid in pull-outs from high-speed dives. These electrically actuated surfaces were mounted ahead of the landing flaps and limited to a maximum deflection to prevent excessive g-loads during recovery.

Empennage

The empennage was a fully cantilevered assembly, with the vertical fin and horizontal stabilizers integrated into a single structural unit. Forward and aft spars were joined through common splice plates, allowing the entire stabilizer assembly to be bolted directly to the fuselage. The rudder and elevators were of Handley Page type, incorporating both static and dynamic balance to improve control at high speeds. All tail surfaces were metal-skinned and constructed using spars and flanged ribs of alclad aluminum alloy.

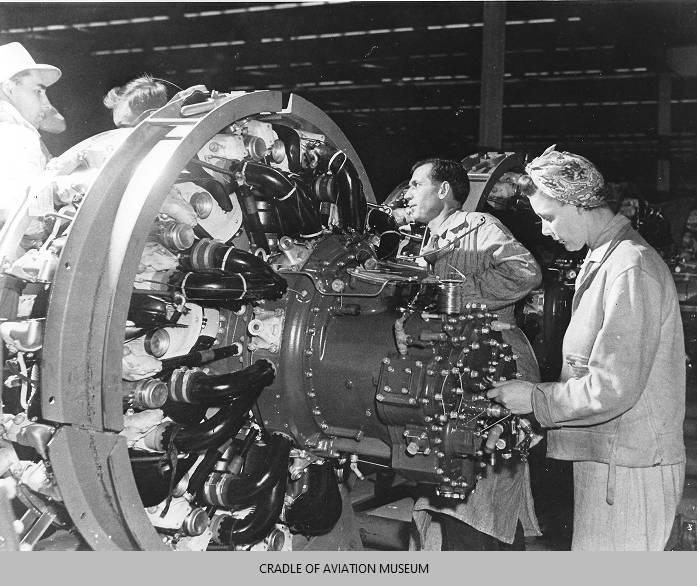

Powerplant and Supercharging System

The R-2800 engine was mounted using vibration-isolating Lord mounts and drove a four-bladed constant-speed propeller, a configuration first proven on the P-47 itself. A NACA-style cowling with hydraulically actuated cooling flaps regulated airflow around the engine, while oil cooling was managed through radiators mounted beneath the powerplant.

Fuel was carried in self-sealing tanks within the fuselage, supplemented by external drop tanks for extended range missions. Electrically driven booster pumps ensured consistent fuel delivery at altitude, while lubricating oil was stored in a magnesium tank equipped with a pendulum system to maintain flow during inverted flight.

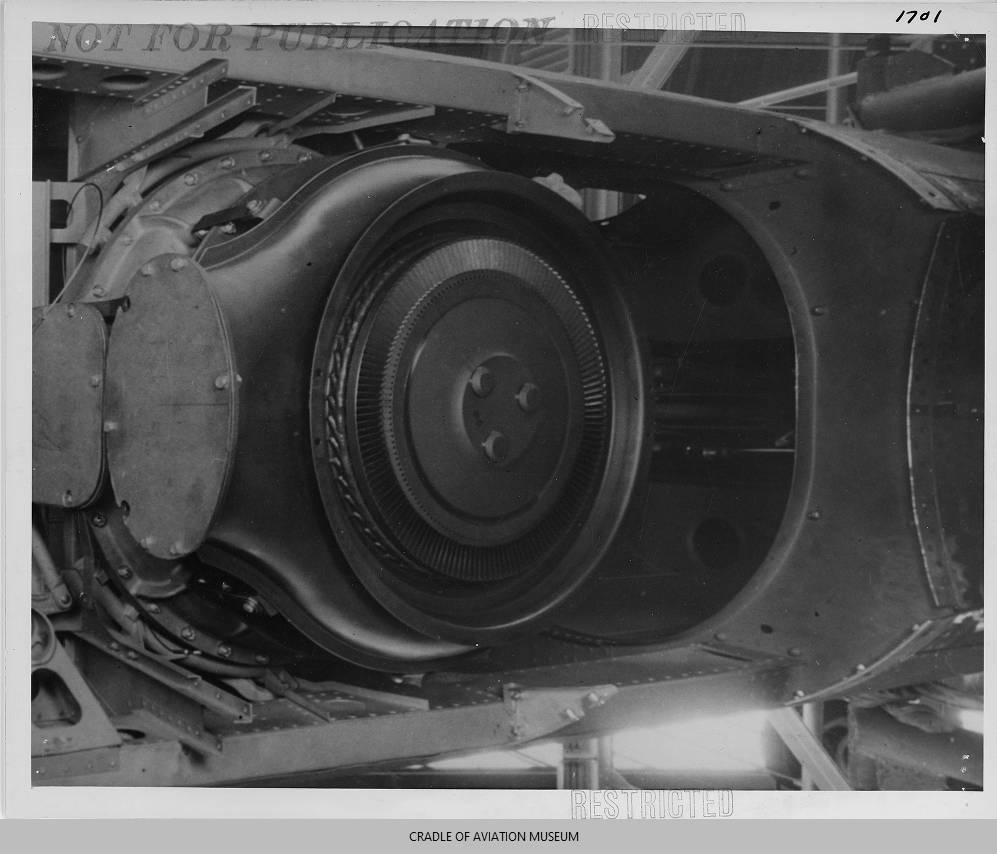

The Thunderbolt’s defining feature was its exhaust-driven turbo-supercharger, mounted deep within the fuselage approximately 22 feet aft of the propeller. Exhaust gases were routed from the engine to the turbine via shrouded piping beneath the fuselage, while compressed intake air passed through an intercooler before being delivered to the carburetor. Waste gates controlled by an oil-operated regulator adjusted turbine speed automatically to maintain pilot-selected manifold pressure.

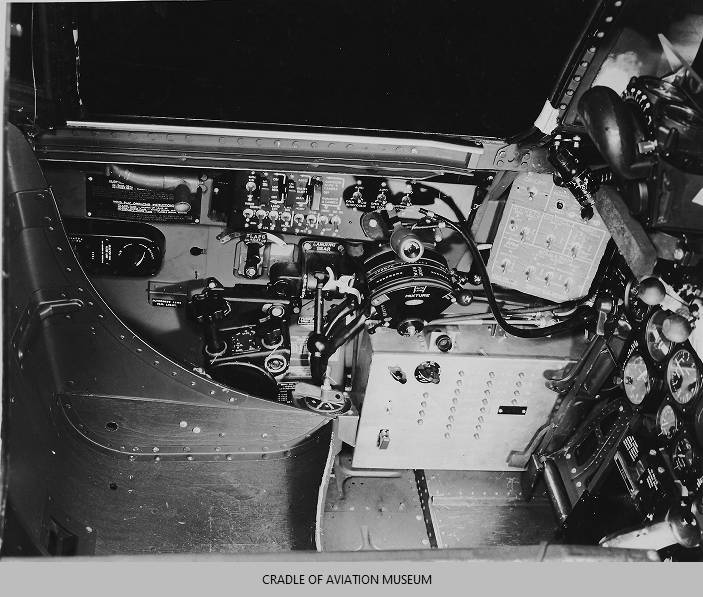

To simplify cockpit workload, the throttle, propeller, and boost controls could be mechanically linked, allowing coordinated power changes with a single lever. For emergency power settings, water injection was employed to suppress detonation and permit higher boost pressures, temporarily increasing engine output beyond normal military limits.

Landing Gear

The Thunderbolt’s landing gear represented another engineering first. To accommodate the large-diameter propeller without sacrificing wing armament or structural efficiency, Republic developed a telescoping main landing gear. When retracted, the gear shortened by nine inches, allowing it to fold inward into compact wheel wells. This innovative geometry preserved ground clearance while enabling a robust wing design. Each main gear unit consisted of an air-oil shock strut mounted within a reinforced magnesium structure. Retraction was hydraulically controlled, with mechanical sequencing ensuring proper locking and stowage. During retraction, displaced air from the shock strut was transferred to an auxiliary chamber to maintain internal pressure balance.

Armament and Protection

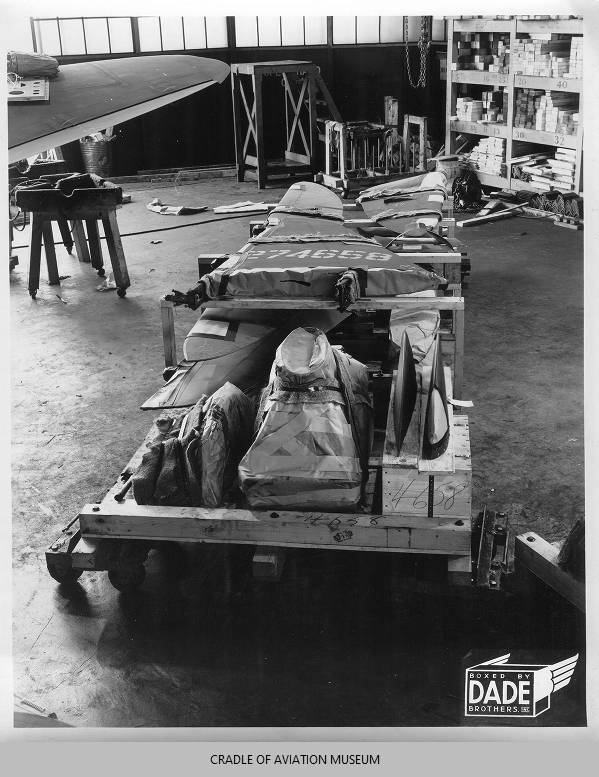

The P-47 carried eight .50-caliber machine guns mounted in the wings, secured in Republic-designed brackets that allowed rapid installation and removal. Ammunition capacity exceeded 350 rounds per gun, while external stores, including bombs and rockets, could be carried on underwing shackles. Pilot protection was extensive, with hardened armor plate installed fore and aft of the cockpit and bullet-resistant glass shielding the frontal area. Combined with its rugged structure and powerful engine, this protection contributed to the Thunderbolt’s reputation for durability and survivability in combat.

Many thanks to Randy Wilson, New York Heritage Digital Collections, and The Cradle of Aviation Museum (COAM) collection.

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.