By Chris Bucholtz

The wheels had just come up on Lt. Frank Allen’s B-26 when his flight engineer, Sgt. Holden came on the intercom with a report no Marauder pilot wanted to hear: “Sir, the left engine is on fire.” The USAAF’s hot new medium bomber already had a reputation as a widow-maker. Losing an engine on takeoff could be deadly, as the drag of an inoperative engine had a tendency to flip the plane on its back at low speed, followed almost immediately by a fatal crash. Allen wasn’t flying a combat mission — he was transporting 12 men and their gear to the San Diego and the Naval Torpedo School. He’d just completed a two-week stint flying anti-submarine patrols from San Diego in the early weeks of World War II, and was looking forward to a return to its delights after time at the muddy Muroc Lake Army Air Field. “My mind was preoccupied with the bad weather that lay ahead,” said Allen. Holden’s calm report didn’t quite register until Allen pressed his microphone button and repeated, “OK, left engine is on fire.”

“Then I suddenly realized what I had said! I looked out the side window and, sure enough, the left engine was on fire! And how!” said Allen. “Flame was pouring out of the engine nacelle, and the cowling was melting off like butter.” Allen pulled back the throttle on the left engine while his mind flashed to other Marauder pilots who had tried to make emergency single-engine landings and didn’t make it. His first impulse was to belly in straight ahead, but the ground ahead was rough. The left engine was still producing power, and with wheels and flaps up, the B-26 was moving at 170mph at 25 feet. Allen made a very flat turn, lined up with the runway, and even managed to get the wheels down (“they locked into place just as I hit”). He’d saved himself, his crew and passengers — and even the B-26, which was repaired with parts from a wrecked B-26 and was back in the air the next day. “I was never so glad to get back on the ground in my life,” Allen said. “By all rules of flying, I never should have gotten away with it, and the next time it happened,” he vowed, “I’d land straight ahead — wrecked airplane or no wrecked airplane.”

Many early Marauder pilots weren’t as lucky as Allen — training in the Marauder was a dangerous proposition, because pilots had never had such a high-performance machine, and because there was little time to learn its peccadillos. Ordered straight off the drawing board, B-26 instructors had scarcely more time in the type than their students, with predictable results. A string of crashes at McDill Army Air Field in Florida led to the catch phrase “One a Day in Tampa Bay,” and the plane’s relatively small wing area brought it the nicknames “Baltimore Whore” and “Flying Prostitute,” because its wings offered it “no visible means of support.” In 1942, with a growing reputational problem, few would imagine that the Marauder would become the U.S. combat type with the lowest loss rate in the war, thanks to better training and improvements made to the Marauder that made it easier and safer to fly.

Development

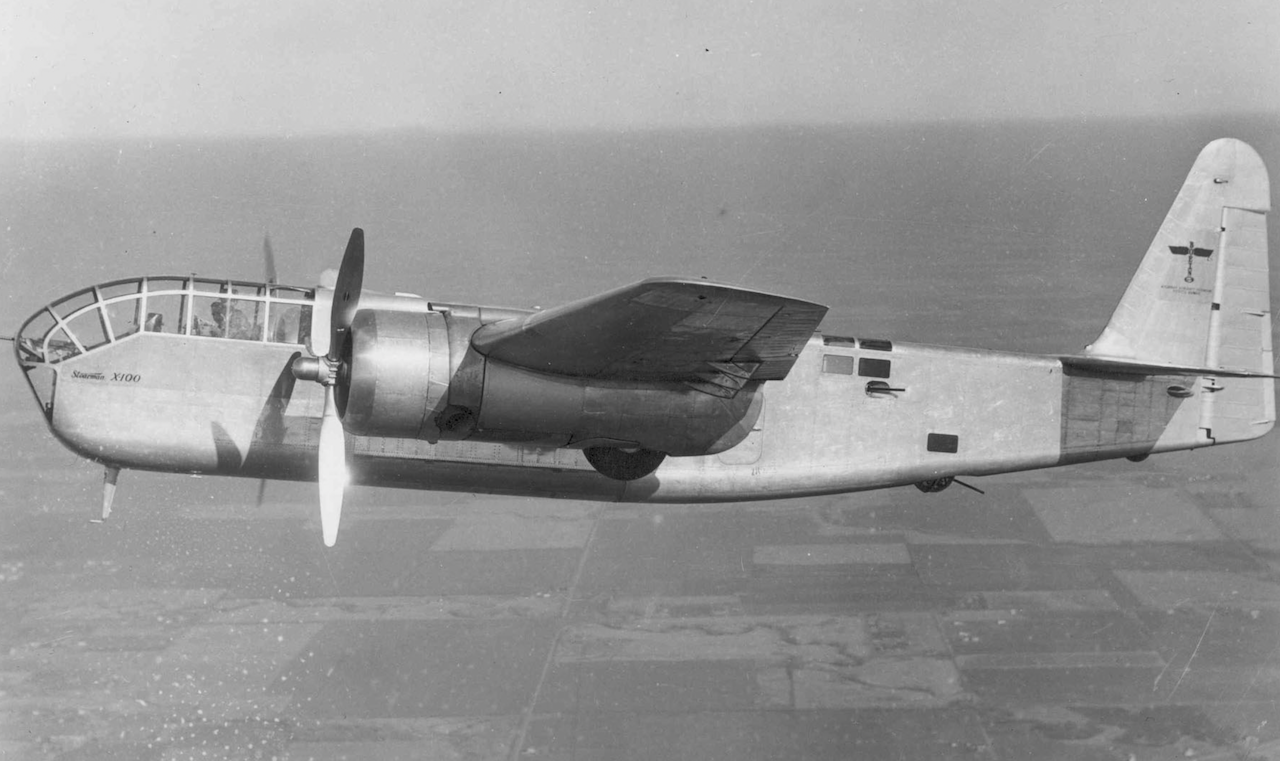

The B-26 Marauder represented the apex of a major leap forward for the Glenn L. Martin Company. In 1933, the company’s B-10 entered service, an all-metal monoplane with an internal bomb bay that required extensive re-engineering by the U.S. Army Air Corps to become a winner, but ended up serving as the USAAC’s first-line bomber for seven years and won the Collier Award for 1933 for the year’s most outstanding contribution to aviation. It also saved the Martin Company from bankruptcy. In 1939, in response to foreign requirements, Martin unveiled the Model 167, which became known as the Maryland in British service. This was followed in 1940 by the Model 187, or the Baltimore, a heavier but more powerful version of the Maryland. In response to the emerging threats posed by Germany and Japan, on March 11, 1939, the USAAC issued Circular Proposal 39-640. This called for a twin-engine bomber with a top speed of 300mph, a five-man crew, armed with four machine guns, and capable of carrying a 3,000-pound bomb load over 2,000 miles. Service altitude was projected between 8,000 and 14,000 feet, with a top ceiling of at least 20,000 feet. The circular authorized the use of the Pratt & Whitney R-2800, the Wright R-260,0 or the brand-new Wright R-3350 engine. The winner would get a contract for 385 planes — and be the first beneficiary of the USAAC’s “abbreviated” procurement process. In other words, the contract would be issued even before a prototype was built.

There were only a few real contenders. Douglas submitted the B-23, an improved take on the B-18 Bolo, with the wings of the DC-3 and an improved fuselage that boasted the first glazed tail-gun position. The existing contract for the B-18 was altered to swap B-23s in place of the last 38 Bolos, but the plane was too slow for consideration. North American Aviation’s NA-62 showed promise; the mid-wing, twin-tailed design clearly pointed toward North American’s eventual triumph in the B-25 Mitchell. Boeing-Stearman’s entry, the XA-21, was a re-hash of earlier designs, resembling a tail-dragger single-tail Mitchell. Martin came up with the Model 179. Head designer Peyton Magruder delivered a plane that was almost art deco in its look — a cylindrical, tapering fuselage, with a shoulder-mounted wing that tapered evenly to its wingtips. Tucked into its streamlined nacelles were two R-2800 radial engines, and the plane boasted a Martin-designed upper turret with two .50-caliber machine guns, supplementing one in the nose and another in the tail.

All these proposals went to a board appointed by the Secretary of War for evaluation. The Model 179 scored 813.6 points in the board’s evaluation, with the NA-62 tallying 673.4 points and the B-23 610.0. The XA-21was doomed by a 442.7 point score. The B-23 would become a footnote (it was briefly considered for the Doolittle raid); the NA-62 would evolve into the B-25 and see long, effective service. The Model 179 would become the B-26 — hailed by the board for its speed, design, and for Martin’s history of building bombers. The B-26 would carry a “heavier bomb load higher, farther, and faster” than any twin-engine ever built. Martin’s assertion that it could build its first example in nine months and deliver 204 planes within 23 months didn’t hurt, either.

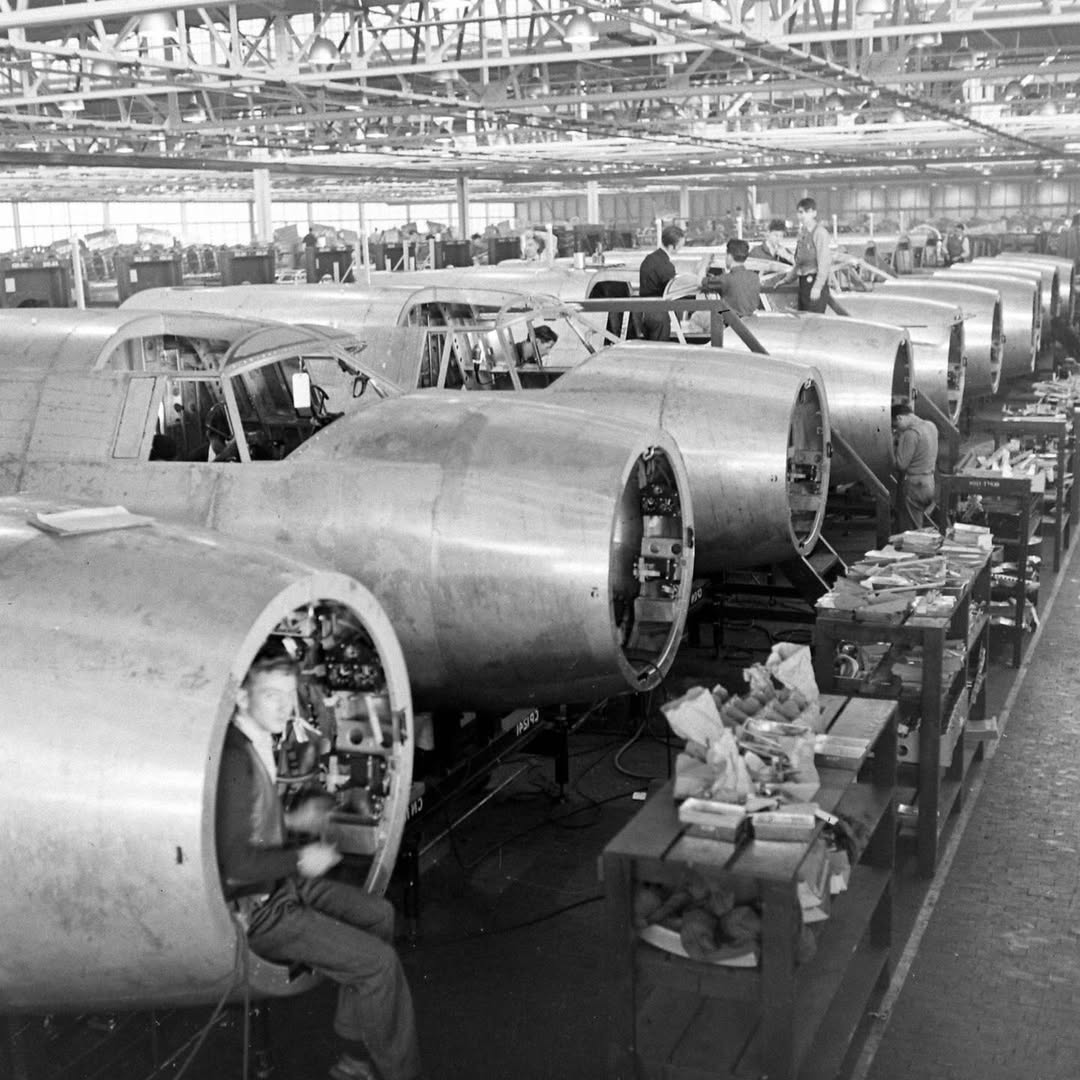

On July 25, 1939, the USAAF issued the contract for the B-26. Mow, Martin had to take a design on paper and make it real, amid crushing geopolitical, economic, and engineering pressures. Changes began to be suggested almost immediately. In October 1939, when wind tunnel data suggested the original twin-tail arrangement created greater drag than a single tail, it was revised, substituting a single vertical fin and horizontal stabilizers mounted with significant dihedral. A mock-up finished in November 1939 brought more suggested changes: blown nose and rear transparencies without the original heavy framing, the addition of waist guns, and other details. A year later, on Nov. 25, 1940, the first B-26 lifted off. It showed tremendous promise — a top speed of 323mph, service ceiling of 25,000 feet, and a range of 3000 miles. But the USAAF could not leave the off-the-drawing-board design alone. In 1941, Martin handled a variety of recommended changes, some impractical (like pressurization of the fuselage) and others truly needed, including the redesign of the wing to give it greater area for safety’s sake. The dangers of single-engine operation also led to an increase in the size of the vertical fin and rudder.

During the test program, the Army Air Force noted that “landing and takeoff characteristics of the B-26 were disappointing, although it was a fairly good plane in the air. The plane could be landed satisfactorily by experienced pilots when the proper weight was carried in the tail.” The problem was that there were few experienced B-26 pilots — at this early stage, even instructor pilots had no time in the type, and the B-26 didn’t fly like other bombers. If it was a “hot ship,” that’s how it needed to be handled. Training by former B-10 and B-18 pilots applying the techniques used for those docile machines was simply inappropriate, and warnings during development about a “hot ship” didn’t help the plane’s reputation. At the same time, mechanical issues with the landing gear, engine, propellers, hydraulic system, and pilot’s escape hatch led to accidents and changes on the assembly line. The hazards of losing engines on take-off became well-known. The other dangerous factors for new pilots were the nose-wheel landing gear — a novelty at the time — and the high landing speed, normally around 100mph. Marauder men had to adapt to these in a hurry; many did not, and it contributed to a reputation that struck fear into some aviators assigned to the type that persisted into 1942, especially in the European theatre.

The USAAF’s counter to this fear was to show pilots how the B-26 could be flown when it was approached properly. The man chosen to do it had just been given command of the 4th Bombardment Wing (Medium), which was scheduled to fly B-26s in the invasion of North Africa in November. Prior to that assignment, he had commanded the raid on Tokyo flown from the carrier USS Hornet. This pilot was Jimmy Doolittle. “Hap (Arnold) asked me to check into the problem and recommend whether the B-26 should continue to be built,” Doolittle wrote in his autobiography, I Could Never Be So Lucky Again. “I travelled to several flying training schools and B-26 transition units, gathered the student pilots together, and asked them what they had heard about the B-26 airplane. Almost all said they had heard it wouldn’t fly on one engine, you couldn’t make a turn into a dead engine, and landing it safely on one engine was just about impossible.

“To prove them wrong, I lined up on the runway, feathered the left engine during the takeoff roll, and made a steep turn into the dead engine, flew around the pattern, and landed with the engine still inoperative. I did it again in the other direction with the right engine feathered. And I did this without a copilot, which made a further impression. This convinced the doubters that all of these ‘impossible’ maneuvers were not only possible but easy if you paid close attention to what you were doing.” Doolittle also recommended that transition training be extended, which became easier as B-26 combat veterans rotated home from the Pacific. The reality was that his demonstrations didn’t address the major problems Marauder trainees faced — like electrical system failures that resulted in a loss of propeller pitch control — but they were an enormous morale boost, and they kept the B-26s flying while problems were ironed out by Martin.

TO WAR IN THE PACIFIC

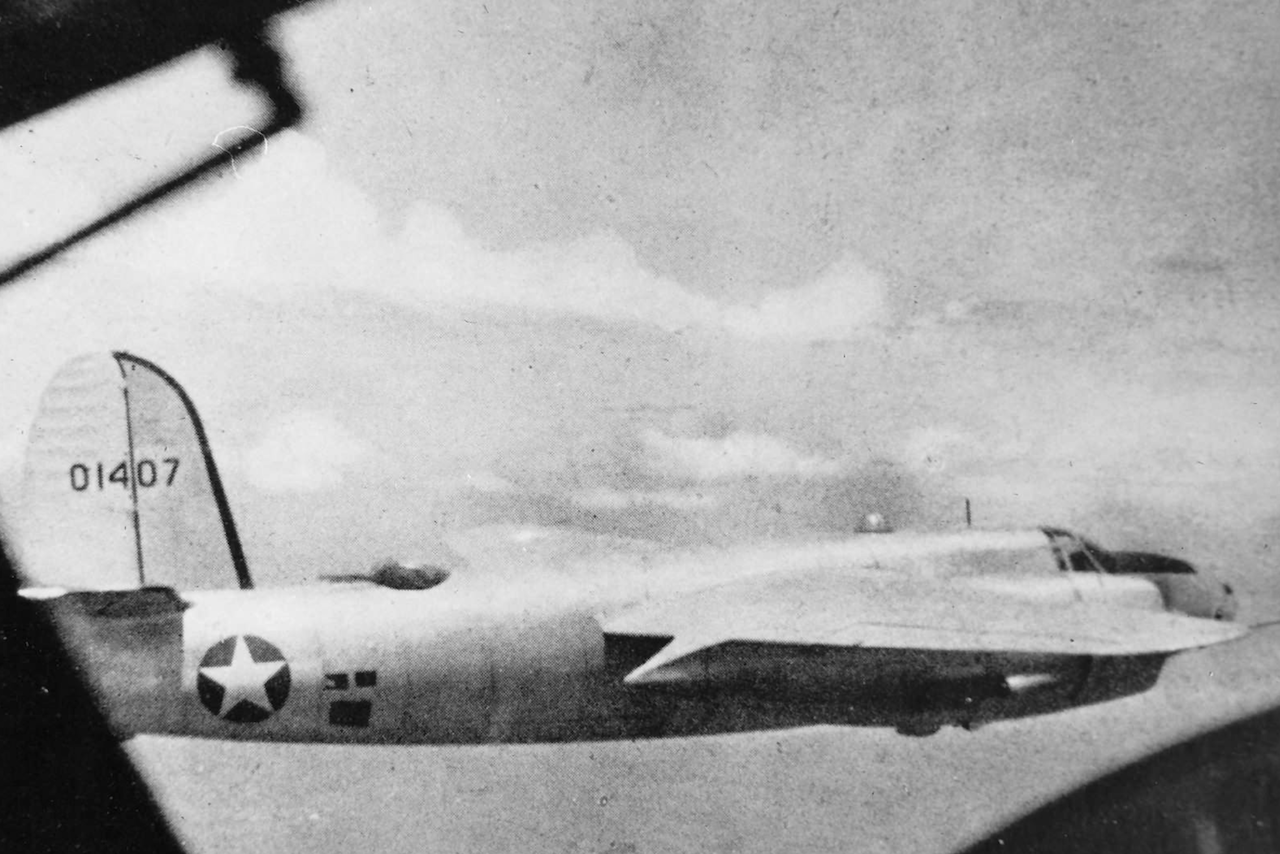

By the time Doolittle’s demonstrations saved the B-26 program, the Marauder had already been in combat in the Pacific for some months. In late March 1942, groups of Marauders from the 22nd Bomb Group made a multi-day island-hopping trip to Australia to set up base as part of the new U.S. Fifth Air Force. The group supported allied actions against the Japanese in the region, starting with a mission to Rabaul on April 5, 1942. The 22nd stripped its early B-26 and B-26As of paint, earning the nickname of “the Silver Fleet,” a play on Easter Airlines’ trademark. They also added extra guns to the waist positions of their planes and additional guns in the nose. The 22nd played an important role in interdicting Japanese ships bringing troops and supplies to New Guinea. On 21 July 1942, a group of Marauders from the 22nd were the only Allied aircraft to attack the Japanese convoy heading for Buna, and took part in the subsequent fighting around Gona and on the Kokoda Trail. In 1942, the group hit targets in New Britain and New Guinea, and they helped soften up Lae in advance of the Australian landings there. But the 22nd was at the far end of the Allied supply lines, and the USAAF had switched B-26 priorities to Europe. The “Silver Fleet” gradually dwindled, more from wear and tear than from enemy action. By Christmas, 1942, the group had just 16 operable planes, which were consolidated into a single squadron while the other two were converted to B-25 Mitchells. In mid-1944, the group switched to the B-24.

Meanwhile, in the central Pacific, the Marauder helped turn the tide of the war. When codebreakers revealed Japanese plans to attack Midway in June 1942, the USAAF sent to the island what it felt it could spare from the protection of Hawaii. That included a quartet of B-26s – two B-26-MAs from the 18th Reconnaissance Squadron, 22nd Bomb Group, and two B-26B-MAs from the 69th Squadron, 38th Bomb Group, units preparing to re-position to Australia when they (plus a fifth B-26, which crashed during training) were commandeered into local defense. These Marauders would be sent against the Japanese fleet not with bombs, but with torpedoes. Though they never scored a hit, they may have played a crucial role in the U.S. victory. In November 1941, a directive had been issued requiring the installation of torpedo equipment on all B-26s. Martin developed an external rack mounted on the lower fuselage keel former to carry the 2000-pound Mk. 13 Mod 1 aerial torpedo, and in December 1941, testing began. The torpedo was supposed to be dropped at 80 percent of the aircraft’s maximum speed, but for the B-26, that was 225mph; the Navy found the Mk. 13 torpedo could not be dropped at speeds beyond 160 mph without it being damaged, and it needed to be dropped from 200 feet in order to enter the water at the optimum angle. Testing showed the B-26 would not handle well at speeds below 175mph without the use of flaps, making torpedo attacks in the Marauder highly hazardous for its pilots and crews. Worse yet, the Mk. XIII torpedo wasn’t up to snuff. Work on the Mk. XIII began in 1925, but spotty funding meant the first examples were not ready until 1932, and the first air drops took place in 1935. The weapons were essentially hand-made, and they were expensive – in 1931, each torpedo cost $10,000. This made the Navy reluctant to expend them in tests, and as a result, there were no live-fire tests of the Mk. XIII.

The original Mk. XIII placed the propellers aft of the rudders. Only 144 of the “Mod 0” torpedoes were built. The “Mod 1” relocated the propellers forward of the control surfaces, and the result was an extremely unreliable weapon. By 1943, the Mk. XIII Mod 1’s shortcomings had become obvious; a study conducted that year found that, of 105 torpedoes dropped at speeds above 150 knots, 20 percent ran cold (the motor did not start), 20 percent sank, 20 percent ran off course (usually pulling to the left), 18 percent ran at the wrong depth, and 2 percent ran on the surface. The Mk. XIII also suffered from exploders that simply did not work. The magnetic exploders often caused early detonation, and the backup contact exploder’s firing pin usually broke on impact with the target and failed to cause the exploder to fire. The Marauder men on Midway had no knowledge of this, however. On June 4, a PBY spotted the Japanese Fleet and Midway sent its aircraft into action. The four B-26s departed at 0625, led by Capt. James Collins Jr. At 0710, the Marauders spotted the Japanese carriers and started to descend for their attack, then turned left and back to the right to avoid anti-aircraft fire. This maneuver positioned them so a flight of six TBF-1 Avengers, intent on their own target, crossed directly in front of the Marauders as they started their attack runs. At 700-800 feet, Zeros of the Japanese combat air patrol hit the formation head-on, “and that’s when the formation broke up,” said Lt. James Muri in a 2005 interview with historian Jon Guttman. The B-26s dove hard for the deck, leveling off at 200 feet to prevent the Zeros from getting to their exposed bellies. Even so, the Zeros caught Lt. William Watson’s B-26, which shuddered, lost speed, and “disappeared spectacularly beneath the water,” as a Japanese officer aboard battleship Haruna reported.

The three remaining Marauders bore in on their target, the fleet flagship Akagi. Collins made his attack from 20 degrees off the bow of the carrier, but the ship was turning into the attack to present the smallest possible target. At about 800 yards, with anti-aircraft fire holing his plane, Collins dropped his fish, and Muri’s navigator watched the torpedo enter the water and speed toward the target – but there was no explosion. Muri held on even longer – to 450 yards – before releasing his weapon. His B-26-MA, “Susie-Q,” was shot full of holes, the dorsal turret was struck by cannon shells, and all three of his gunners were wounded. He wanted out of the flak for at least a moment – and so he flew directly bow-to-stern over the Akagi. The ship’s guns couldn’t fire across the deck, and the Zeros held off for fear of strafing their own flagship. “If I had lowered the gear, we would have rolled the whole length,” Muri said. In the nose, bombardier Lt. Russell H. Johnson opened fire with his .30-caliber machine gun, killing two men in the No. 3 anti-aircraft mount and wounding three others. The fourth B-26, piloted by Lt. Herbert Mayes, pressed its attack, but as it dropped its torpedo, it was fatally stricken. The flaming Marauder hurtled toward the carrier, passed just 10 feet above the bridge – housing the Combined Fleet’s staff – and crashed into the ocean. Collins ducked into a cloud, while Muri ran for home, dodging Zeros returning from the Japanese morning strike. Both B-26s were badly damaged – all of “Susie-Q’s” propeller blades were damaged, “and we stopped counting holes after we reached 500,” said Muri – but they still outran the Japanese fighters. They joined up with the sole surviving TBF-1 for the flight home. Collins landed with no nose gear; Muri blew a tire on touchdown and skidded off the runway. The two B-26s were pushed aside and eventually were bulldozed into the atoll’s lagoon. No torpedo hits were scored by any of the Marauders, but the close calls with Muri and Mayes’ B-26s shook Japanese Admiral Chuichi Nagumo and convinced him of the need for a second strike on Midway. He ordered his aircraft to be re-armed from anti-ship to high-explosive weapons. This threw off his launch timetable and set in motion a series of events that would culminate in U.S. Navy SBDs surprising his carriers when they were most vulnerable, with ordnance stacked on their hangar decks. At the same time that Midway was under attack, the Japanese launched an operation in the Aleutian Islands off Alaska to seize the small islands of Attu and Kiska. To screen their invasion forces, the Japanese sent carriers Ryujo and Junyo to bomb Dutch Harbor, which they feared could be expanded into a naval and submarine base. Dawn on June 4 saw miserable weather conditions – fog, rain, and clouds – but five B-26s of the 77th Bomb Squadron, 28th Bomb Group, launched from Otter Point to hunt for the Japanese fleet, to no avail. The 73rd Bomb Squadron, based at Cold Bay, Alaska, launched five torpedo-armed Marauders under Col. William Eareckson at 1220 toward coordinates reported by the PBYs. Soon, the formation broke up in the heavy fog, and Eareckson ordered the planes to land at Otter Point, but Marauders flown by Captains Henry Taylor and George Thornbrough continued their search. They found the Japanese fleet after it had recovered its strike aircraft, and, with weather conditions marginal, the two B-26s tried to set up a torpedo attack.

Ducking into a rain squall to disguise their approach, Taylor and Thornbrough soon lost sight of each other. When the Marauders broke out of the squall, the Japanese threw up an intense anti-aircraft screen. Taylor emerged from the clouds at 100 feet and nearly collided with a carrier; he pulled up, turned, and tried to set up a run on another nearby vessel when an anti-aircraft shell smashed the Plexiglas nose and wounded bombardier Lt. Vernon Peterson. Taylor ducked into a cloudbank while the co-pilot pulled the wounded bombardier into the cockpit for attention. Circling, Taylor made a second run, but the Marauder was again hit by fire, and he aborted the run, ducking back into the weather. As he began a third attempt at the carriers, escorting Zeros were waiting for him; raked by several A6M2bs, Taylor jettisoned his torpedo and nursed the damaged Marauder back to Otter Point. Thornbrough was also frustrated during his attacks. Twice he had started a run on a carrier, and twice the expertly-handled Japanese ships turned into him, presenting a narrow bow-on target. In both cases, Thornbrough ducked into the clouds, climbed, orbited, and dropped back to attack. For his third attack, Thornbrough decided to dive-bomb a carrier, using his torpedo as a 2000-pound bomb. As he pushed the B-26 into a dive against the twisting Ryujo, it occurred to him: without the impeller turning through a number of rotations, which it had to do in the water, the warhead would not arm. By then, it was too late. Thornbrough yanked the release handle. The torpedo came off the Marauder’s belly, and it rocketed over the Ryujo’s deck, plunging into the frigid Bering Sea waters without exploding. Thornbrough brought the B-26 back to Cold Bay and ordered it loaded with a more conventional payload of 500-pound bombs and took off into increasingly poor late-afternoon weather. After failing to find the Japanese fleet, he turned back and radioed that he was above the now-socked-in Cold Bay. Then, like dozens of other aircraft that would fight in the unforgiving Aleutian theatre over the next two years, Thornbrough and his crew disappeared without a trace.

Meanwhile, the five B-26s from the morning search mission, under Capt. Owen Meals was readied for another search carrying torpedoes. The Marauders were just warming up when D3A1 dive-bombers and A6M2b fighters attacked the field. The Marauders were not hit, but it wasn’t until 2040 that the base could be organized sufficiently for the aircraft to take off. One plane suffered a blown tire and aborted its take-off; another developed engine trouble and returned to base. That left Meals, Capt. Kenneth Northamer and Lt. Brady Golden; they spread out to broaden the area they could visually scan. Meals and Northamer were rewarded 25 minutes later by glimpses of the Japanese fleet sailing in the twilight beneath a blanket of thick overcast. Meals dove to attack and launched his torpedo at a large, unidentified vessel; his tail gunner reported seeing an explosion on the port bow of the ship. Northamer also surprised his target and reported torpedoing a vessel in its stern. Golden never spotted the Japanese; all three planes returned to Cold Bay safely. USAAF reports gushed that the B-26s had sunk a carrier. In reality, no Japanese ships were sunk, and the reports of the tail gunners had been wildly optimistic. The B-26s of the 28th Bomb Group would fly missions against the invading Japanese on Kiska and Attu – with conventional bombs – for several months before they were replaced with B-25s. Two squadrons of B-26s from the 38th Bombardment Group also flew out of Henderson Field starting in 1942, but by the end of April 1943, these, too, had been replaced by Mitchells.

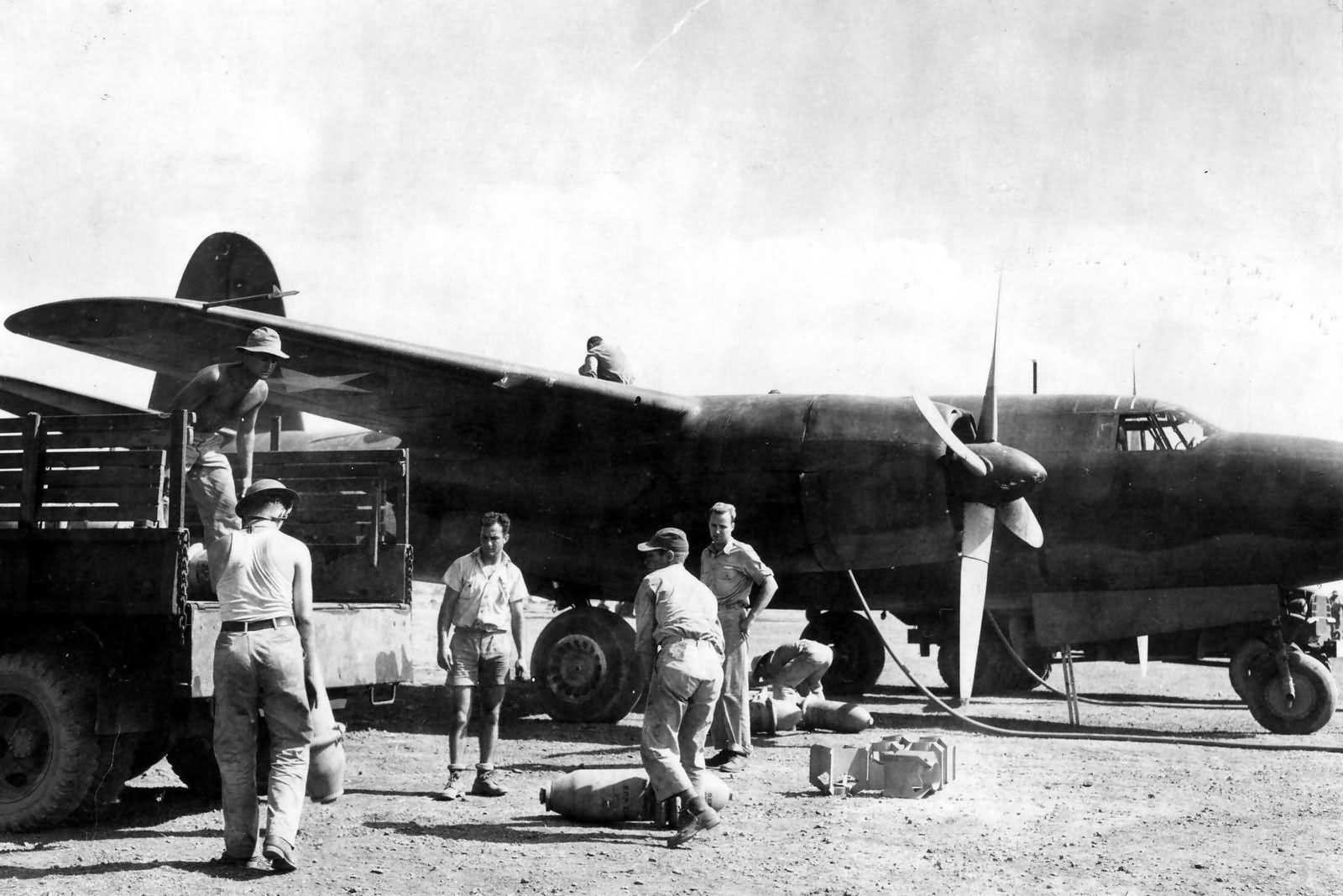

MARAUDERS IN THE MED

While the Marauder’s baptism by fire came in the Pacific, it would find its true calling in Europe, starting with the arrival of three bomb groups in North Africa in December 1942, following the Operation Torch landings. The three groups to deploy — the 17th, 319th, and 320th Bombardment Groups of the 12th Air Force — initially used the same tactics that had been used in the Pacific: low-level strafing and pinpoint bombing. But German flak was much thicker and more accurate than what the Japanese could muster at the time, and after two months, the B-26s were ordered to medium-level work, with the exception of shipping attacks. Instead of their earlier practice of making individual attacks, the Marauders flew in formations, dropping the bombs on the signal of the bombardier in the lead plane of the formation.

When the German forces finally surrendered in North Africa, the target for the B-26s became Italy. The B-26s became key tools in softening up Sicily in advance of the landing in July 1943, pounding shore installations, coastal shipping, and airfields, greatly reducing the air threat posed to the invasion by the Luftwaffe. Once allied forces landed, the Marauders blasted key German strongpoints and interdicted supply routes. Sicily fell in mid-August; from there, the Marauders went to work on the Italian mainland. In February 1944, the B-26 groups were among the air units that bombed the abbey at Monte Cassino, setting the stage for a month-long battle in the ruins. A month after the initial attack, Gen. Mark Clark ordered another all-out raid on the abbey, and the B-26s earned kudos for their accurate bombing, placing 90 percent of the bombs on target. It wasn’t until April that Monte Cassino fell to the Allies. 12th Air Force Marauders continued their work in Italy and, after the Operation Dragoon landings, in southern France, flying from bases in Sardinia, Corsica, and, eventually, France itself.

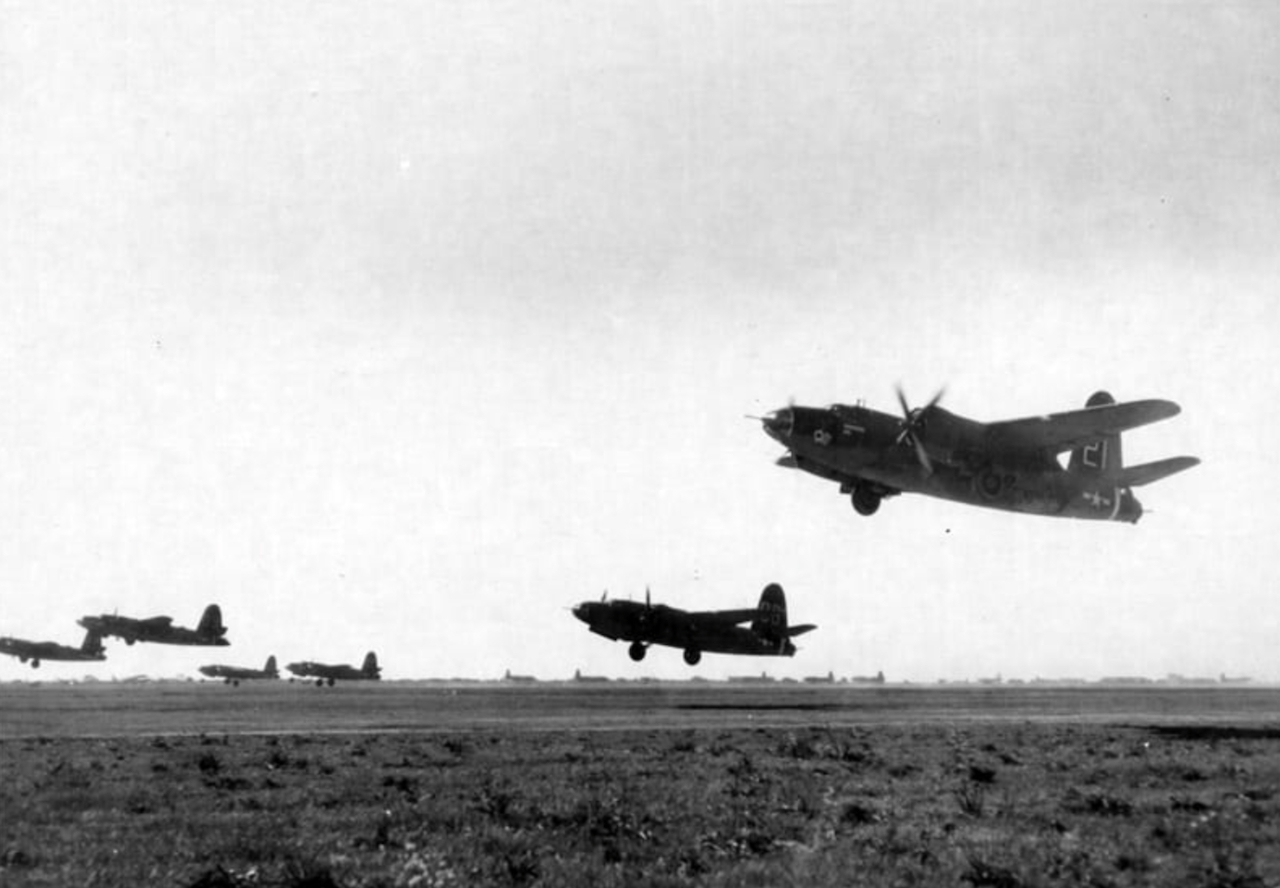

NORTHERN EUROPE AND THE NINTH AIR FORCE

Five months after the Marauder’s debut in the Mediterranean, the Army Air Forces began operations over Northern Europe. Again, the Pacific tactics of low-level attack were initially employed and yielded good results when the 322nd Bomb Group of the Eighth Air Force flew a mission to the Velsen generating station at Ijmuden, Holland, on May 14, 1943, from which 11 of 12 aircraft safely returned to Britain. Three days later, the group attempted the same mission with an 11-plane force; one aircraft aborted, and the other 10 were all lost to flak, fighters, and a mid-air collision. Immediately, the B-26s were ordered to higher altitudes, and the next 11 missions were conducted without loss. The Eighth Air Force had no real idea of what to do with the Marauder; early thinking envisioned B-26s striking targets in France to absorb German fighters, allowing B-24s and B-17s to fly their missions with less opposition. That plan fell apart in the face of the Luftwaffe’s strategy of holding fighters out of the range of U.S. fighters. The USAAF also floated the idea of using Marauders as “heavy fighters,” flying escort for the B-17s and B-24s. This idea was totally impractical because the Marauders flew far faster and had less range than the heavy bombers.

By August of 1943, three B-26 groups were in operation in England. In October, a reorganization of the Army Air Forces in Europe moved the Ninth Air Force from the Middle East to England and made it the tactical arm, complementing the Eight Air Force’s strategic role. The Eighth’s B-26s and A-20s were transferred to the new Ninth Air Force, allowing them to play a critical role in the run-up to D-Day. The Ninth’s B-26 force —which swelled to eight groups by May 1944 — was first used as part of Operation Crossbow, the strikes on suspected V-weapon sites in France. From December 1943 to May 1944, the Marauder force hit these targets, as well as marshaling yards, bridges, and gun emplacements. Initially, they operated like heavy bombers, bombing as a single large formation; later, tactics changed so groups would break into units of four to six bombers, with the intention of bombing more accurately and minimizing collateral damage.

By now, there were aircrews with enough experience to rotate home into instructor roles, and the groups began to receive an influx of second-generation Marauder men. “The men of the 598th Squadron at Rivenhall gave us a warm welcome,” said Stan Walsh, a bombardier/navigator who arrived for service with the 379th Bomb Group in May 1944. “We were the first new crew to join them, with a brand new airplane. They had suffered losses and needed to know they hadn’t been forgotten. They did not brag; they made us feel welcome. As we watched buzz-bombs in the distance toward London, they explained the danger and said they had bombed the launching sites in occupied France. Lt. Col. Allen, squadron. CO, and his assistant, Maj. Gus Williams was informally friendly and glad to have us on board.”

Starting in May, the Marauder force concentrated on airfields within a 130-mile radius of Caen, and also targeted radar sites. On May 24, the limitations on bombing bridges across the Seine were lifted, and the B-26s were called on to drop those bridges to isolate the battlefield. Hitting a narrow target like a bridge took skill and accuracy, said Walsh. “The technique, plotted by intelligence and photo interpreters, was to have the bomb run across the bridge at an angle,” Walsh said. On other targets, especially in Germany, “the bomb run approach course would depend on the location of anti-aircraft gun positions – if known,” said Walsh. “For example, heavily defended Frankfurt Airport had fewer guns on one side, so we were routed to approach from that direction. Unfortunately, that had us flying right into the sun – I couldn’t see a thing. I hit the landing field, alright, but don’t ask me where.” When the invasion started, Marauders stepped up their interdiction tasks and mixed in missions to neutralize German guns and fortifications in cooperation with ground forces. Lt. George Parker of the 596th Bomb Squadron, 397th Bomb Group, flew on the group’s first mission of that day and recalled that the weather on the way to the continent was miserable. Near the Isle of Wight, “we discovered breaks in the overcast and let down over the water to approximately 5,000 feet,” said Parker. “After breaking through… Wow! Behold, ships, warships of all sizes and descriptions appeared below, in one continuous line, scattered in various formations. Near the Cherbourg area, our battleship and cruisers were blazing a huge bombardment on the French coast. A smoke screen was laid to the left of our course. And gun batteries from Allied ships as well as German coastal defenses were causing one helluva sight.” There was little time to take it all in; air traffic was dense, and the group bombed its target, the gun positions at Les Dunes de Varreville near Utah Beach, and got out of the area as quickly as possible to avoid collisions. Each group flew multiple missions this day and through the rest of June and July, weather permitting. Often, the Marauders would be escorted by bomb-carrying P-47 Thunderbolts; if no enemy aircraft were encountered, the Thunderbolts would add their destruction to that already wreaked by the Marauders.

In August, as theAllies broke out of the Normandy beachhead, the Ninth’s squadrons moved across the channel to bases in France to stay in range of their targets. This led to a nomadic existence for the B-26 units, which leapfrogged across France throughout the summer and fall of 1944, isolating the battlefield by striking logistics targets across France and Germany. “Our main task was interdiction, knocking out bridges, rail, and road targets,” wrote pilot George Howard of the 598th Bomb Squadron, 397th Bomb Group. “Our group had a good record over bridges, but these were often the most well-defended targets. Rare were the occasions that we didn’t run into some flak — mostly, it was heavy. Many times, the aircraft that I was flying was hit by shell splinters, but no one in the crew was ever injured. And we always got back to base. You never heard the explosion above the engine noise, but you often felt the concussion and the rattle of shell fragments hitting the plane. Sometimes bits would come up, hit the armor plate at the back of your seat, and rattle around; that was worrying.” Throughout the fall of 1944, the Ninth Air Force’s Marauder units moved east across France to new bases, many of which were either improvised in the fields by the engineers or were re-purposed Luftwaffe facilities. “After we moved to France, we were more appreciative of the runways in England,” Howard wrote. After his group operated from a perforated-steel planking (PSP) field on the Cherbourg Peninsula, they moved to a former Luftwaffe base at Dreux, “where the runways were paved, but conditions were still pretty grim.” Unlike the strategic bombers’ crews, the Ninth’s men often lived in tents and partially ruined buildings, with the constant scourge of mud to contend with. Other moves found them at relatively intact former Luftwaffe bases.

Starting in October 1944, the weather curtailed B-26 operations. The 379th Bomb Group, for example, managed only four missions that month, and November started with rain, which turned to snow. As December arrived, the Marauders were largely unable to operate, which allowed the Germans to move troops into position for their winter offensive in the Ardennes, which started on December 16. “We felt helpless, stuck on the ground in non-flyable weather,” said Stan Walsh. “We heard an informal talk that we might have to evacuate. Just scuttlebutt. There was a scare that enemy paratroops might drop so we mounted a guard on each hardstand.” On Dec.23, the skies cleared, and the Ninth Air Force struck back in force. “Everybody was airborne,” Walsh said. “So were the Germans.” Because of the need for tactical support of the ground troops, the Ninth Air Force’s P-47 groups were also tasked with bombing missions and were unavailable for escort. As a result, the Ninth Air Force lost 41 B-26s on a single day, the bloodiest day in the B-26’s history.“We left on this mission in good spirits because we figured it would be a milk run,” said Capt. Marvin Schulze of the 379th Bomb Group. On the way to hit a railroad bridge at Eller, Germany, “flak was experienced early all the way to the target,” wrote pilot George Parker of the 596th Bomb Squadron in his diary. One Marauder “had a direct hit near the top turret, and the tail was blown completely off the aircraft. One crewman was thrown from the ship with a backpack on, apparently unconsciously sailing through the air to meet disaster. One or two chutes were seen, which may have gotten out of ‘Bank Nite Betty’ — we hope, wishfully.”

After reaching the target and dropping their bombs, the group started a left turn to head home. “About a minute later, I heard every gun on our ship blazing away,” said Schulze, “and then it was like all hell broke loose. About 50 fighters attacked us using company front tactics. Two window ships went down. My number five man got his tail shot off.” “Casey Stangle was flying lead window, leaving the target, when two Fw 190s slipped up and loaded him full of lead from behind,” said Parker. “His tail guns were apparently jammed since the Fw’s just throttled back and fired approximately 10 seconds before peeling off. Casey’s gunners got one Fw and, after he started down, probably out of control, the tail guns were unjammed, and the tail gunner began firing and shot down an Fw-190.”

All told, the 397th Bomb Group lost 10 aircraft, its worst day of the war. Of the 33 aircraft the group launched, only eight returned in flyable condition. The pattern was similar across all the B-26 units in the theatre that flew that day – the 322 Bomb Group lost its pathfinder and another group aircraft to fighters, while two others fell to flak. The message was received loud and clear by the Ninth Air Force: medium bombers were just as vulnerable to fighters as the heavies, and as the Germans were backed into Germany, their desperate defensive efforts required fighter escorts. Losses dropped to just 20 B-26s out of almost 4000 sorties in January 1945, even though the bombers inflicted fearful losses on the enemy as it retreated following the Ardennes offensive. For example, on Jan. 22, 1945, the 387th and 394th Bomb Groups found as many as 1500 vehicles backed up at bridge choke points and stuck these traffic jams with great efficiency. Damage to the Marauders during this period was so frequent that machines were often transferred between groups to maintain proper formation strength for missions. It was also clear that the Marauder’s days were numbered — the Douglas A-26 was now replacing A-20s with some Ninth Air Force units, and Marauder manufacturing was starting to wind down, with the last one rolling off the assembly line two months before the war ended in Europe. In February 1945, the Marauders took a central role in Operation Clarion, a paralyzing attack on the German transport network. One wrinkle was thrown in — after bombs away, the Marauders were given permission to strafe targets of opportunity. After some initial trepidation, crews found the Marauder an excellent gun platform and eagerly engaged German transport with the plane’s .50-caliber machine guns. Pushing the Wehrmacht into an ever-shrinking territory meant the flak became increasingly heavy; February saw 67 aircraft lost during 6624 sorties. But the condensed German territory also meant more targets; cells of three and six Marauders were thrown at bridges, rail stations, road junctions, and repair facilities. These small groups permitted greater flexibility, but also left the B-26s vulnerable to air attack. On Feb. 26, 1945, the 396th Bomb Group was jumped by 20 fighters east of Arnhem, losing three planes.

In April, with the war’s end in sight, the 323rd Bomb Group encountered a new enemy. Returning from the target, the group saw what one pilot thought was an A-26 overtaking the group. Suddenly, one of the formation aircraft belched smoke and fell out of formation in a steep dive. Only then did the group recognize they were under attack by a Me 262. A second jet shot down the lead plane before speeding away. On April 20, another Marauder was lost when a Me 262 pilot from JV.44, distracted by his jammed cannon, collided with the left propeller of a 323rd Bomb Group Marauder. The Me 262 was lost, but the Marauder made it home — its prop blades had been bent so uniformly by the speedy jet that there was no noticeable vibration! Other JV.44 jets swarmed in to attack; three bombers were shot down, one was written off, and 10 more were damaged. Four days later, five JV.44 jets attacked the 322nd and 344th Bomb Groups, and in the process, Gen. Adolf Galland was wounded and knocked out of flying for the rest of the war. Galland said he disliked attacking B-26s the most of any Allied aircraft because of their heavy armament and tight formations. May 3 saw the B-26s’ swan song in combat when four pathfinders from the 1st Pathfinder Squadron led four groups of A-26s to attack an ammunition dump at Stod. With nothing left to bomb, the B-26 force remained on the ground until VE Day, except for a few leaflet missions.

The end of the war saw the rapid drawdown of the Marauder force. Most were scrapped in Germany, often by former German military personnel. A few groups retained their Marauders for occupation duty, but only until they could re-equip with the A-26 Invader.T he A-26 inherited not just the mission of the Marauder, but when the postwar USAF dropped the “A” for attack aircraft, the very designation B-26 that the Marauder had carried so proudly. The plane originally thought of as a widow-maker accumulated a stellar record for getting the job done and getting her crews home; over the course of the war, with an aircraft lost for every 143 sorties, she proved to have the lowest loss rate of any allied aircraft.