The World War II gallery of the National Museum of the United States Air Force contains some of the most historic fighters, bombers, transports, and trainers flown by the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II, but is also home to several aircraft flown by the Axis Powers. While these consist primarily of German and Japanese aircraft, from the Messerschmitt Bf 109 to the Mitsubishi A6M Zero, one of the rarest on display is the only Italian aircraft in the collection. This is the museum’s Macchi C.200 Saetta (Lightning), one of the rarest fighters of World War II left in existence. But how this Italian fighter ended up in the National Museum of the USAF is a story full of twists and turns that reveals an incredible tale of a war trophy left to rot, which became the subject of a loving restoration to the aircraft’s full glory.

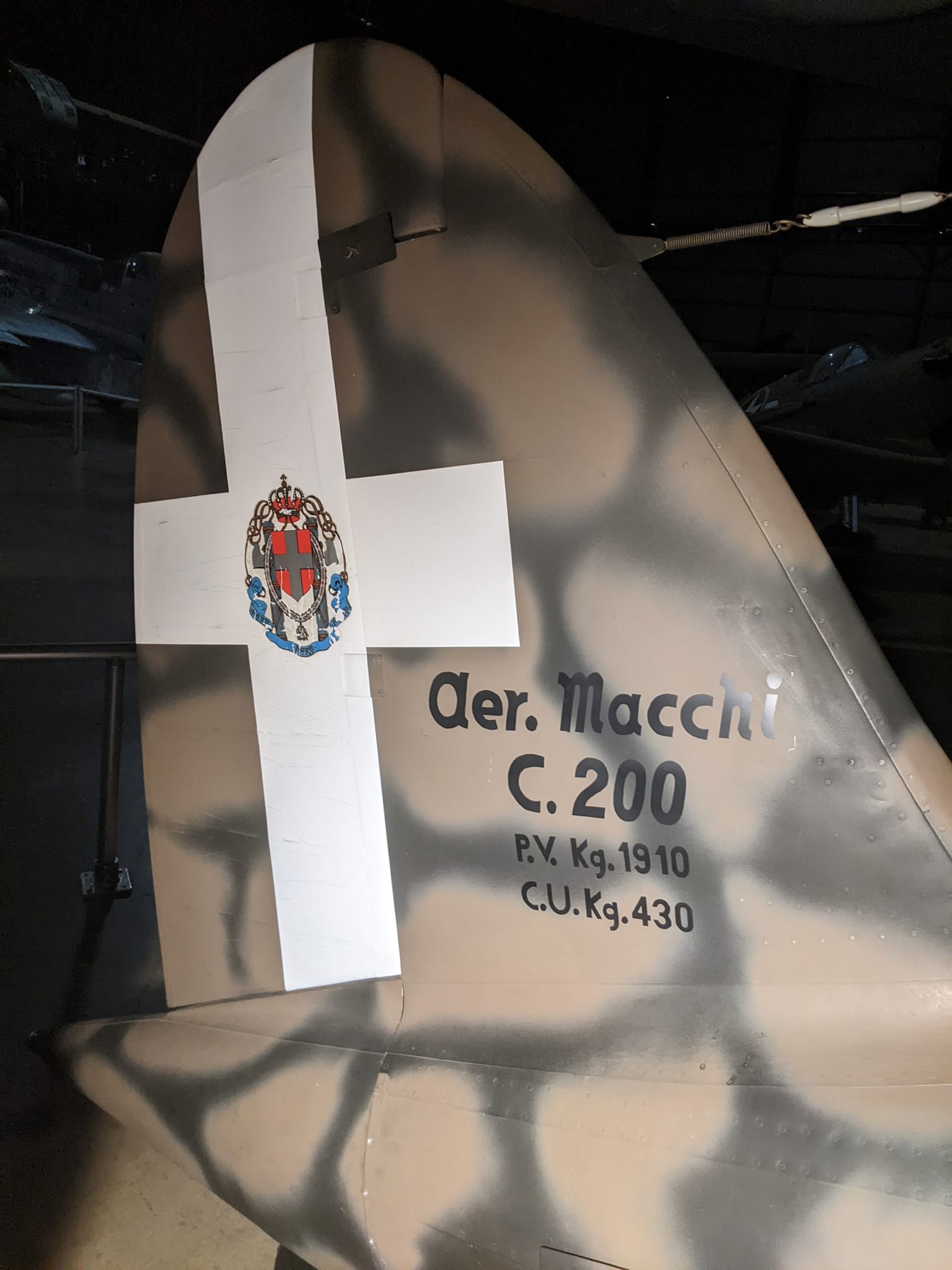

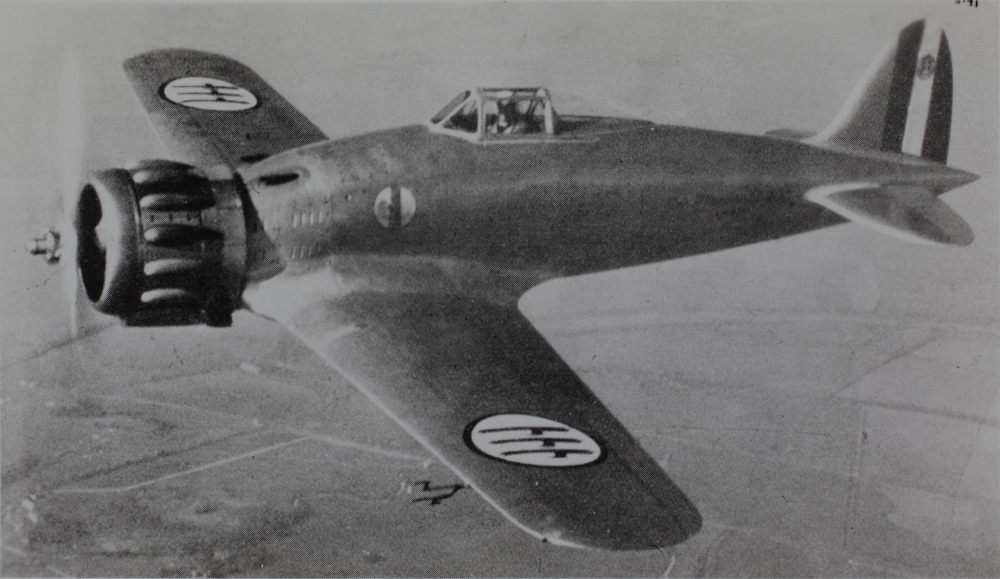

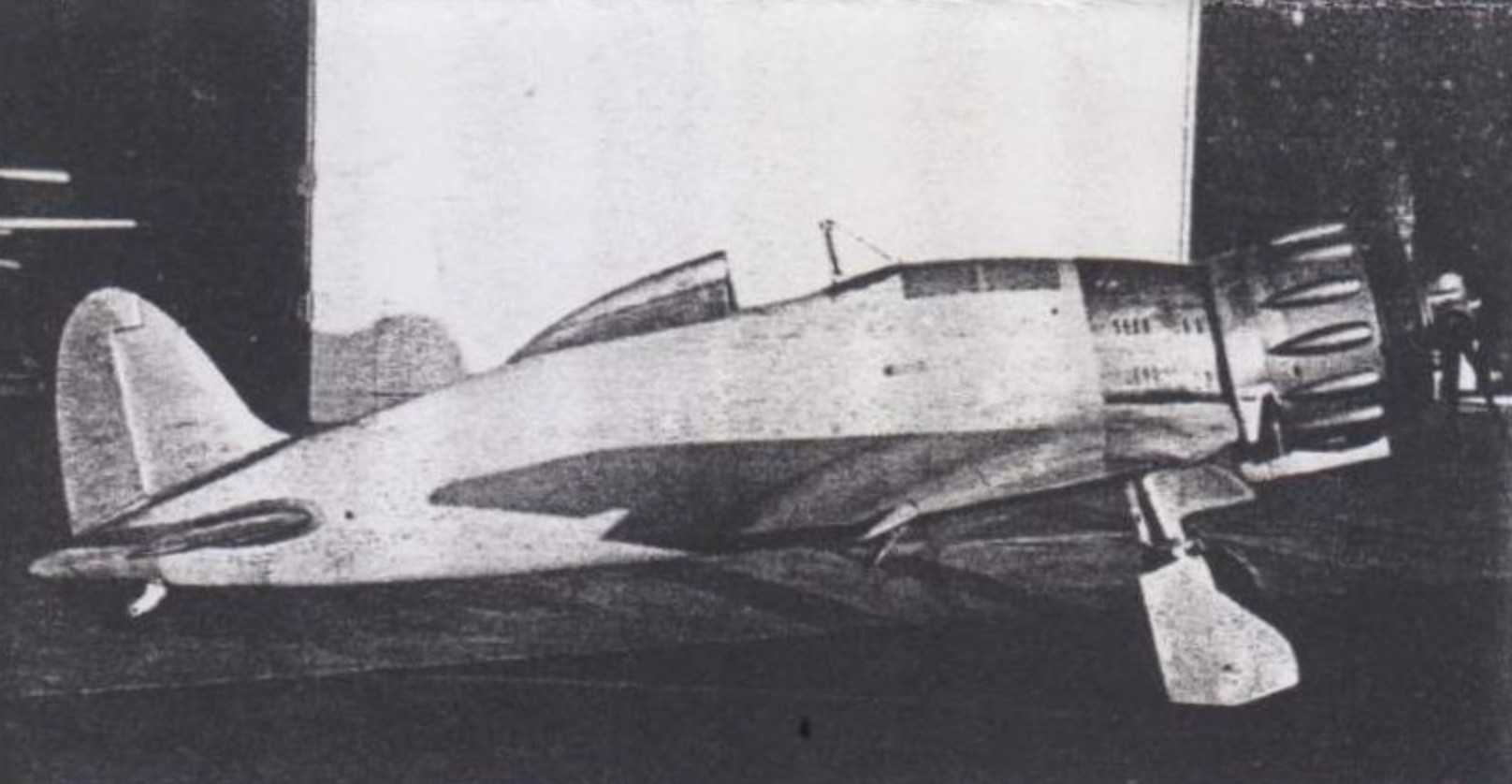

By the mid-1930s, Italy’s Regia Aeronautica (the Royal Italian Air Force) realized that with its rivals in Europe adopting fast monoplane fighters at a time when its fighter arm was still equipped mainly with biplanes, the country would have to adopt a new, more advanced design to act as an interceptor. At Aeronautica Macchi, designer Mario Castoldi, who had come to prominence for designing many of the seaplane racers that Italy used to compete for the coveted Schneider Trophy, set to work on his latest project, a low-wing, cantilever monoplane fighter with retractable landing gear, armed with two synchronized 12.7mm machine guns firing through the propeller arc and powered by a Fiat A-74 radial engine. The result was the Macchi C.200 Saetta, with the prototype first flying on December 24, 1937. Earlier that year, Macchi’s rival, Fiat Aviazione, developed its monoplane fighter, the G.50 Freccia (Arrow), which first flew on February 26, 1937.

Both fighters were low-wing cantilever all-metal monoplanes with the same Fiat A-74 twin-row, 14-cylinder air-cooled radial engine, the same armament of two Breda-SAFAT 12.7mm machine guns, and both were fitted initially with enclosed cockpits that Italian fighter pilots rejected in favor of open cockpits. When Italy declared war on France and Britain on June 10, 1940, both fighters represented the most current fighters in the Regia Aeronautica. Still, even before Italy declared war, it was realized that even more advanced fighters were necessary, leading to the development of both the Macchi C.202 Folgore (Thunderbolt) and the Fiat G.55 Centauro (Centaur) with license-built German Daimler-Benz engines powering these fighters.

From June 1940 to mid-1943, the Macchi C.200 Saetta was the most widely deployed Italian fighter of the war. After its debut in Italy’s brief Jun 1940 campaign in France, the C.200 saw combat from Malta to Yugoslavia, from Libya to Greece, and even saw combat in the Soviet Union in the skies of Ukraine and Russia. The Saetta proved an agile fighter that could outturn many of its opponents, though its pilots had to be weary of its tendencies to stall and spin. Yet by 1942, the plane was outdated as a front-line fighter. Both German and Allied fighters could fly faster and had more powerful offensive armament, and the Macchi C.200 Saetta was increasingly being replaced by its successor, the Macchi C.202 Folgore, with production of the C.200 coming to a halt in October 1942.

By the time Italy surrendered to the Allies in 1943 and the Italian Civil War between the Allied-aligned Kingdom of Italy and the German puppet state known as the Italian Social Republic began, the few surviving C.200s were increasingly relegated to use as fighter trainers, with no frontline duties. The German Luftwaffe even used a handful of Saettas as fighter trainers as well. After the war, the last Macchi C.200s were retired in 1947, and of the 1,153 examples built, only two intact survivors, plus the fuselage of a C.200 with an unknown serial number, remain in existence.

During the Second World War, many Macchi C.200s were constructed not only by the Aeronautica Macchi factory in Varese, but also under license at the Breda Aeronautica factory in Sesto San Giovanni. It was in the Breda plant that the aircraft of our story came to life. According to Italian aviation historian and fellow Vintage Aviation News contributor Luigino Caliaro, the aircraft now displayed at the National Museum of the USAF was among 90 C.200s produced as part of the 19th series production batch built at Sesto San Giovanni. Italian aviation historian Gregroy Alegi states, however, that while later restoration efforts in Italy and the National Museum of the United States Air Force identify the aircraft as the Matricolo Militare (Italian for Serial Number) MM.8146, no data plates were found on the aircraft to confirm this exact number, but given the research done on this aircraft by Alegi and fellow Italian aviation historian Maurizio Longoni, who is also the curator of Italy’s largest aviation museum, the Volandia Flight Park and Museum near Milan-Malpensa Airport, it is most probable that given the available records of series production and of the Saettas deployed to North Africa, that the NMUSAF’s example is at least “MM.814-“, with MM.8146 being the most likely serial number for this aircraft.

What can be determined is that the aircraft commonly identified as MM.8146 was delivered from the Breda Aeronautica factory in Sesto San Giovanni to the Regia Aeronautica in June 1942 and assigned to the 372a Squadriglia (372nd Squadron) of the 153° Gruppo Autonomo C.T. (153rd Autonomous Group, Caccia Terrestre (land fighter)) at Turin. Shortly afterwards, the 153rd Autonomous Group and the 372nd Squadron were deployed to North Africa, where they were sent to Benghazi, Libya, to continue the fight against the British Commonwealth advancing from Egypt, while the Americans, having landed in Vichy French North Africa, were now advancing from the west through Algeria. By this time, the aircraft was transferred from the 372nd Squadron to another squadron in the 153rd Autonomous Group, the 165th Squadron. But just as MM.8146’s war was beginning, it was about to end.

On November 20, 1942, after their decisive victory against German field marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps at the Battle of El-Alamein, the British Eighth Army under Bernard Montgomery captured Benghazi and its outlying airfields from the Italians and the Germans. Among the multitude of abandoned German and Italian equipment was Macchi C.200 MM.8146, discovered at the K3 Airfield. Despite officially being transferred to the 165th Squadron, which would have seen the fuselage code be repainted from ‘372’ to ‘165’, there had been no time for the Italian ground crews to make this change before Benghazi was overrun, and the aircraft was captured by British forces. In examining further documentation with the author, Gregory Alegi now believes that 372-5 was not MM.8146, but rather another C.200 built by Breda, MM.8327, which was also part of the 372nd Squadron, but was later transferred to the 92nd Squadron before being damaged in an emergency landing 30 kilometers southeast of the Arch of the Philaeni, an archway built by the Fascist regime in 1937 and nicknamed the “Marble Arch” by Allied soldiers. Whatever the identity of the aircraft, the RAF had already captured other Saettas during the North African campaign, but since there is no record that this C.200 Saetta was ever issued with an RAF serial number, it is possible that the aircraft was deemed too damaged to be economical to be restored to flyable condition when it was captured by the British.

After the aircraft’s capture in Benghazi, Macchi C.200 MM.8146 was shipped to the United States. Like the British, they did not evaluate the aircraft for flight testing (in fact, only one Italian fighter in WWII, a Macchi C.202 Folgore captured in Sicily in 1943, was flight tested in the USA, and it was later transferred to the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum (see this article HERE)). Instead, the aircraft was used in war bond drives as a traveling exhibit. It was common for both sides to display captured equipment that was not in immediate need of technical evaluation to be used in war bond rallies to show the public examples of what tools their enemies were using to wage war, and to encourage citizens to contribute to the war effort by purchasing war bonds to help their respective governments pay off the costs of the war. Another example of an aircraft captured in Libya used for war bond drives was Junkers Ju 87 R-2/Trop. Stuka Werknummer 5954, which was later donated to the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, where it remains on display today (see this article HERE). Though there is a lack of documentation to cite specifically where the Saetta traveled in America, it is possible that the aircraft may have only been given a generic label such as “Captured Italian Fighter”, given the fact that Italian aircraft designs were not as recognizable to the American public as where the German Messerschmitt Bf 109 or the Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero. Immediately after the war, many captured aircraft used in war bond drives, which were sometimes wrecks recovered from overseas battlefields, were scrapped without fanfare. Yet Macchi C.200 MM.8146 managed to survive the postwar scrap drives, briefly ending up in the city of Worcester, Massachusetts to be part of a local fair before being acquired by a collector named Albert B. Garganigo, founder of the Princeton Auto Museum in Princeton, Massachusetts.

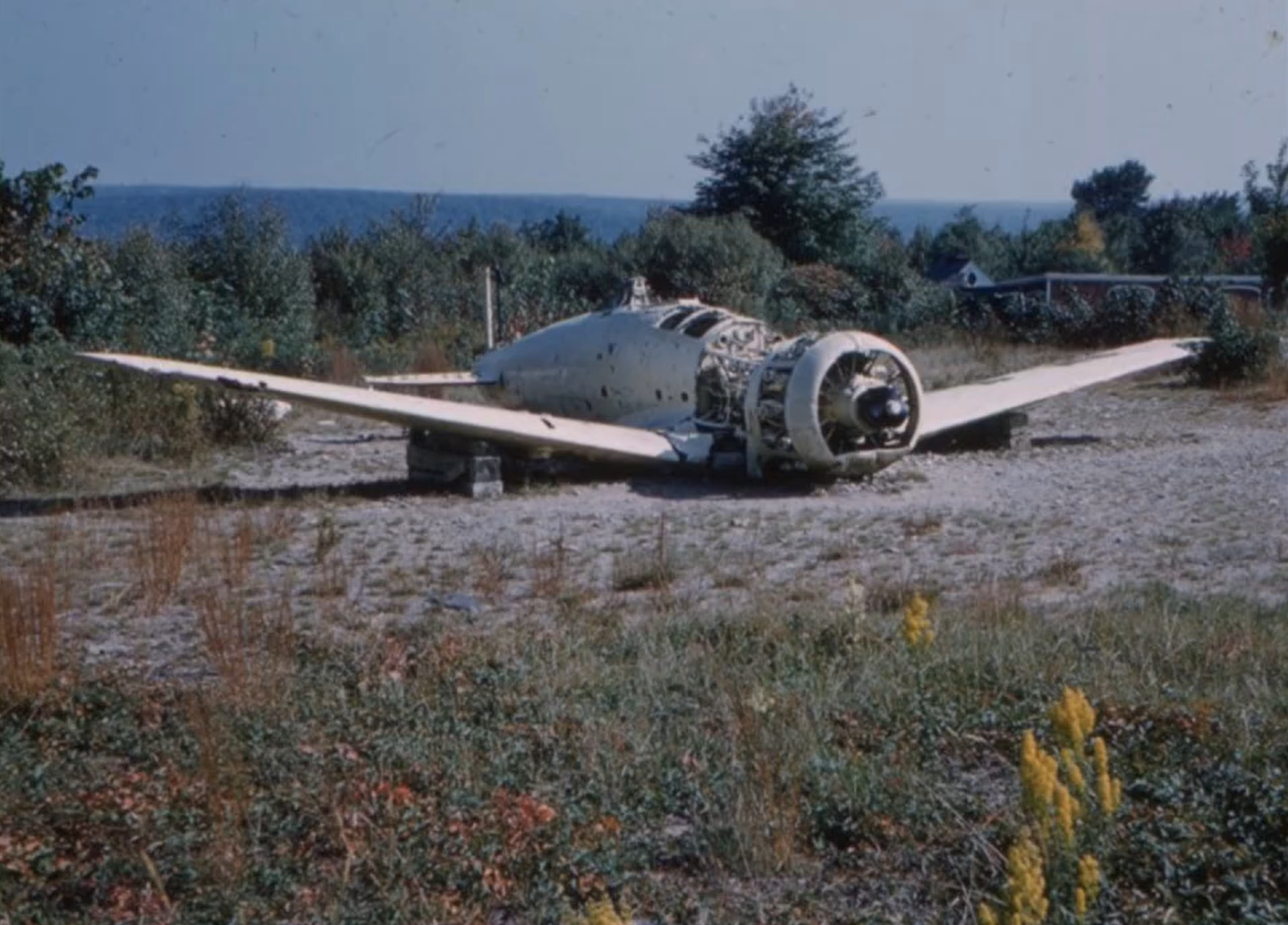

Born in 1893, Garganigo had immigrated with his family from Italy to Massachusetts in the late 1890s and served in the U.S. military during World War I before running home to Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, where he ran the Turnpike Garage and Auto Wrecking Company. In his spare time, Garganigo collected and restored a number of antique automobiles with his family and after buying a farm in nearby Princeton, Garganigo founded the Princeton Auto Museum in 1938. The museum would hold up to 200 antique cars in a barn and several outbuildings totaling 28,000 square feet, with a small railroad around the museum to give rides to visitors and collected all manner of antiques for his museum. At some point, Garganigo acquired the derelict Macchi C.200, and had it displayed outdoors at his museum. Unfortunately, the weather in Massachusetts took its toll on the disassembled airplane, which would still outdoors year-round for almost 20 years. One detail pointed out by Gregory Alegi of the Macchi in Princeton is the presence of bomb racks mounted to the underside of the aircraft’s wings.

In 1963, Albert Garganigo died at the age of 70 following a short illness, but had left no will behind. Soon, the Princeton Auto Museum would close to the public in 1964, and the majority of the automobile collection went to another car museum, Gene Zimmerman’s Automobilorama “History on Wheels” in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The Macchi C.200 Saetta, however, would be acquired by the Connecticut Aircraft Historical Association (CAHA), which founded the Bradley Air Museum, now called the New England Air Museum at Bradley International Airport in Windsor Locks, Connecticut. While the aircraft was being kept in storage, the Bradley Air Museum lacked the resources necessary to restore the Saetta. On October 3, 1979, the Bradley Air Museum was devastated by a Category F-4 tornado that completely destroyed 16 aircraft and heavily damaged 10 more. Given the necessity of restoring what planes could be salvaged from the tornado, the Macchi C.200 remained in storage, waiting for its turn at restoration, and the museum slowly collected what material it could find, from missing parts to engineering drawings.

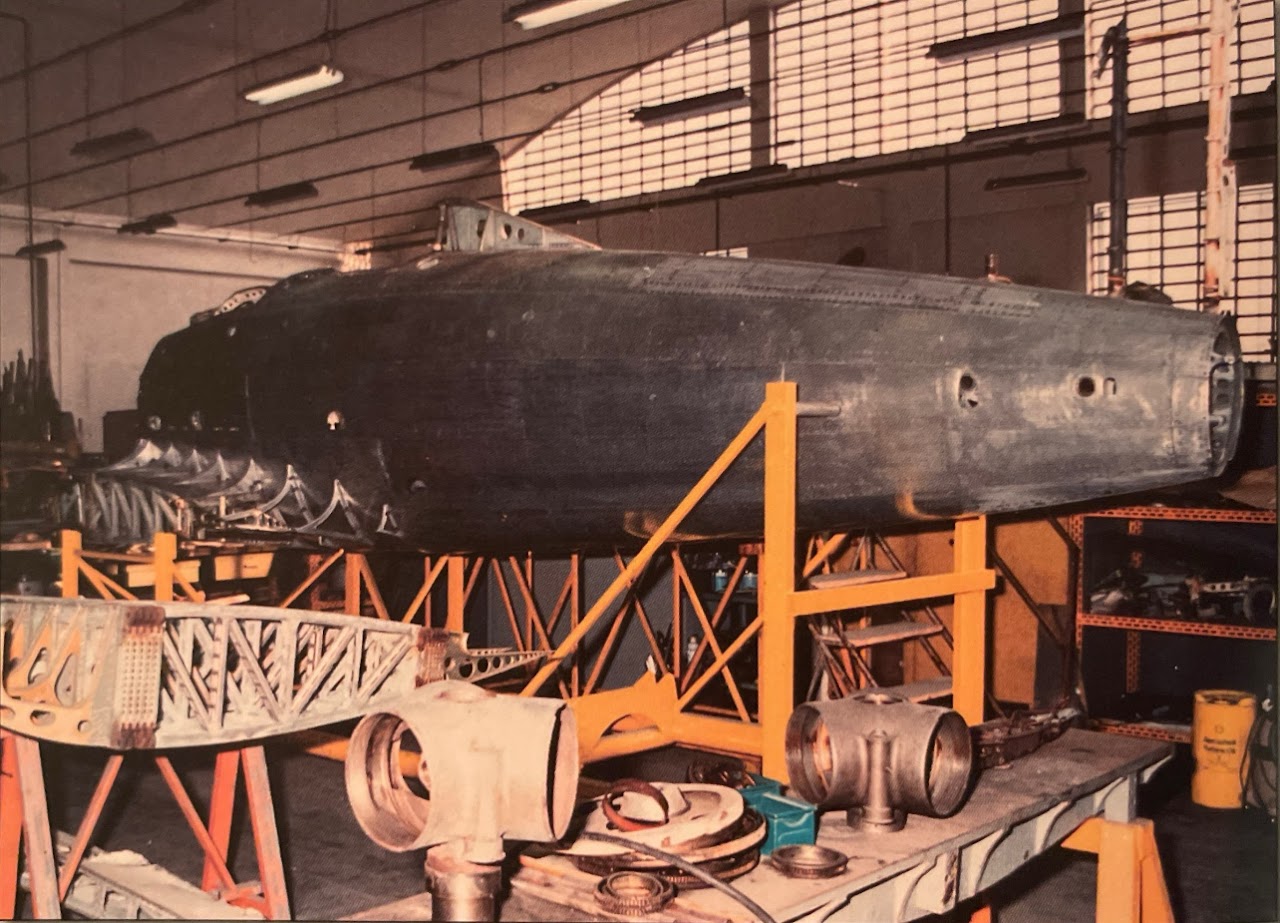

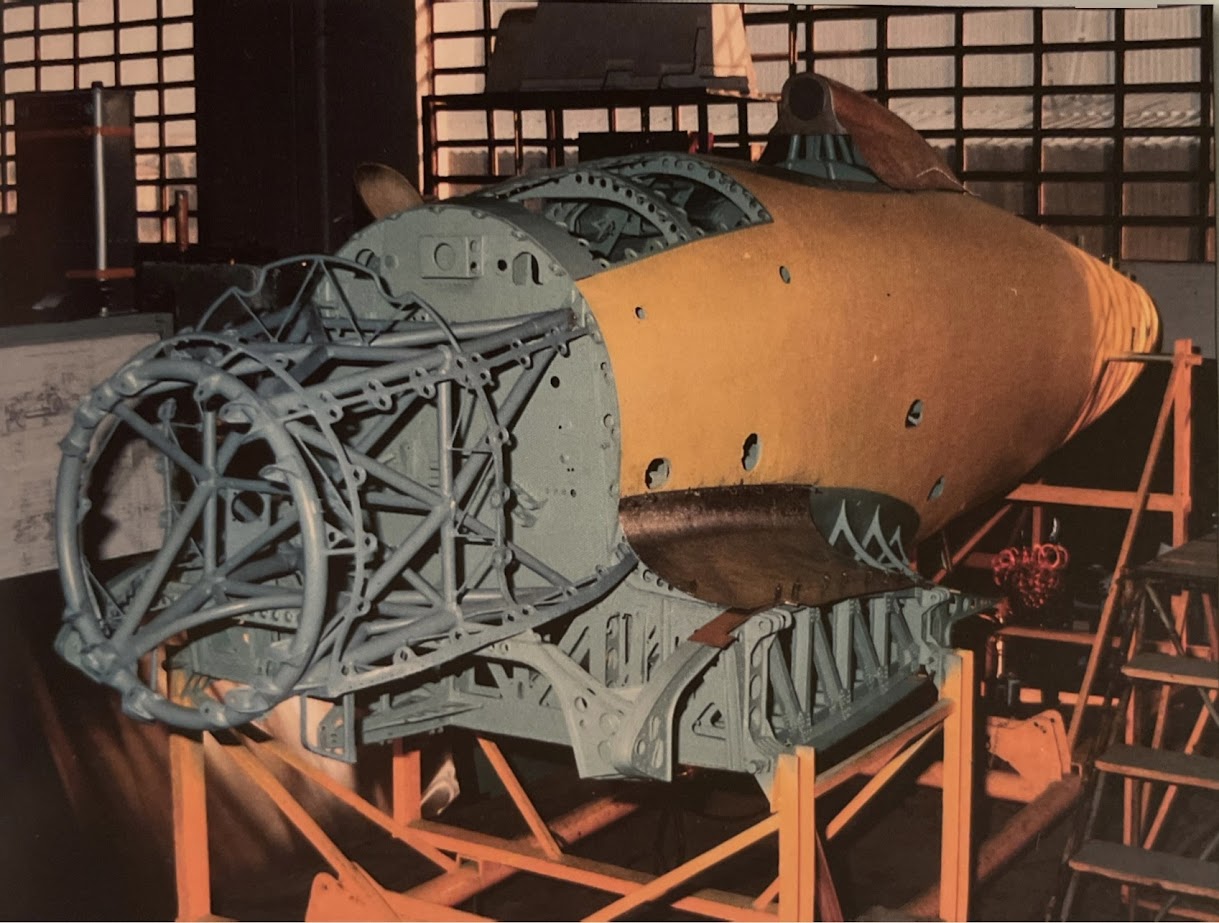

Many at the Bradley Air Museum (renamed the New England Air Museum in 1984) hoped to restore the Macchi, but given its condition and the lack of reference material to go off of, any restoration would need extensive financial resources. In 1988, the New England Air Museum offered the Saetta for sale, on the condition that it be strictly restored as a static display. The museum got an offer from Canadian aircraft broker Jeet Mahal of Vancouver, British Columbia, who would later facilitate the sale of Soviet and German aircraft wrecks from Russia during the 1990s following the collapse of the Soviet Union. While some at the museum were reluctant to see the Macchi leave, Mahal had gotten in touch with Aermacchi (now part of Leonardo S.p.A. after being known as Alenia Aermacchi from 2012 to 2016), and they would complete the restoration at the Aermacchi plant in Italy. After the completion of the restoration in Italy, the aircraft would be shipped to the National Museum of the United States Air Force (then called the United States Air Force Museum) to go on permanent display there. On December 4, 1989, the aircraft arrived at Varese-Venegono Airport, home of Aermacchi’s factory, where the Macchi C.200 had been designed. At Varese-Venegono, a group of volunteers consisting of Aermacchi employees who had just completed one of the final prototypes of the AMX International AMX ground attack aircraft, developed jointly by the Italians and the Brazilians. Plus, the volunteers were also restoring another WWII Macchi fighter in the form of a Macchi C.205 Veltro (Greyhound), MM.92166; now on display at the former Aermacchi office building of the Leonardo S.p.A. plant at Varese-Venegono. The restoration of the Veltro was helpful for the team working on the Saetta, as elements from the design of the C.200, particularly the wing structure, had been incorporated into that of the C.205. The restoration of the Saetta would be conducted in a hangar on the opposite end of the Varese-Venegono Airport from the main Aermacchi plant.

Even with the expertise of the volunteers and the similarities in the designs of the Macchi C.200 Saetta and the Macchi C.205 Veltro, the Saetta’s restoration would prove to be a challenge. Many parts were missing entirely, and many of those that remained were badly corroded. Up to 40% of the wing structure had to be replaced, and most of the lower fuselage had to be completely replaced due to intergranular corrosion in areas where water had collected when it was being kept outdoors in the New England weather. The focus of the restoration, though, was to restore as much of the original structure as possible and replace parts only when necessary. On the wings, the similarities in the internal structure of the wings of the Veltro provided a reference for the restoration of the Saetta’s wings; some sheet metal skins were replaced and flush-riveted into place, while original components that could be reused were cleaned, had surface-level corrosion treated, had primer applied, and were refitted. For the fuselage, the lower portions had new, longerons and formers fabricated and installed, with sheet metal skin riveted onto the structure. Meanwhile, the organization Gruppo Amici Velivoli Storici (GAVS; Friends of Historical Aircraft) helped the team restore what original internal systems on the airframe remained, while taking down and acquiring replacements for missing items for the barren cockpit, such as flight instruments and a throttle quadrant to be refitted into the airplane. On the aircraft’s landing gear, new trunnions were refabricated, while the original oleos and axles were restored. GAVS found a tail wheel assembly, main gear wheels and tires, and assisted in fabricating gear doors from original factory drawings and installing the gear retraction mechanism. Every original component on the aircraft was disassembled, thoroughly cleaned, treated for corrosion, and refinished for reassembly. For the vertical and horizontal stabilizers of the Saetta, some of the internal structure was retained, but the stabilizers mounted to the aircraft’s tail required all-new sheet metal to be applied, and the rudder and elevators had to be refabricated from scratch.

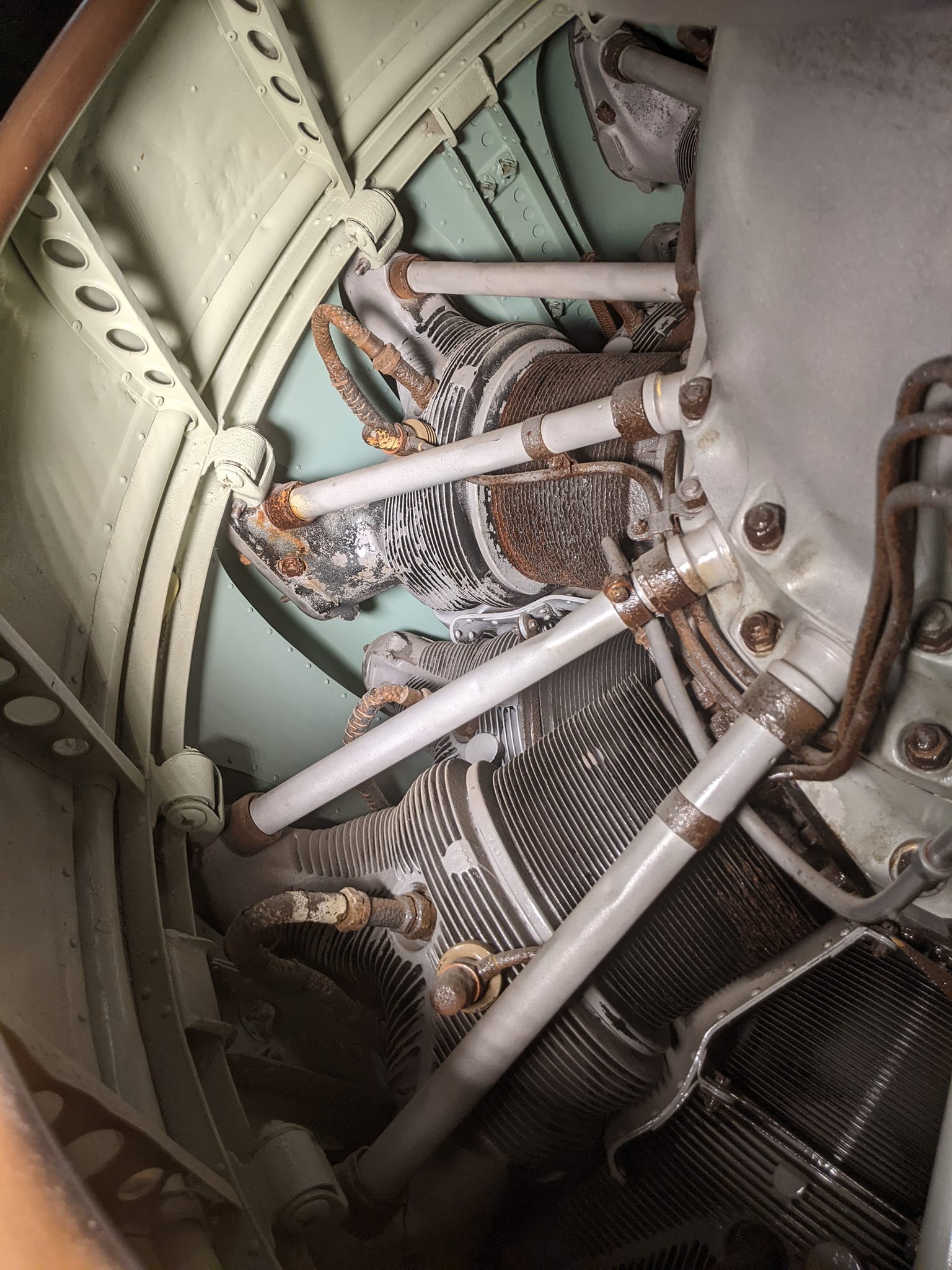

The heart of any airplane is always its engine, and in the case of Macchi C.200 Saetta MM.8146, its Fiat A-74 radial engine was disassembled, treated for corrosion, cleaned up and repainted, with missing parts tracked down and installed by GAVS. Since the aircraft was to be placed on static display after its restoration was finished, the engine was restored to presentable, but not to be run up again. Perhaps one of the most challenging parts of the restoration of the aircraft was the refabrication of the engine cowling, which had to be rebuilt from factory drawings. This was because the cowling required fairings to accommodate the rocker boxes on all 14 cylinders of the aircraft’s Fiat A-74 engine, which all had to be fabricated as part of the cowling. On the Saetta, the leading edges of the engine cowling also house the aircraft’s oil cooler, which was straightened and cosmetically restored, but in order not to replace the original tubing, the cooler was not restored to operational condition. The Italian team that restored the Macchi C.200 Saetta at Varese-Venegono was Vittorio Suigo, Maurizio Longoni, Renzo Bernasconi, Ernesto Valtorta, Mario Biolcati, Giancarlo Martegani, and Giuseppe Zilioli, with Gregory Alegi providing research material for the restoration.

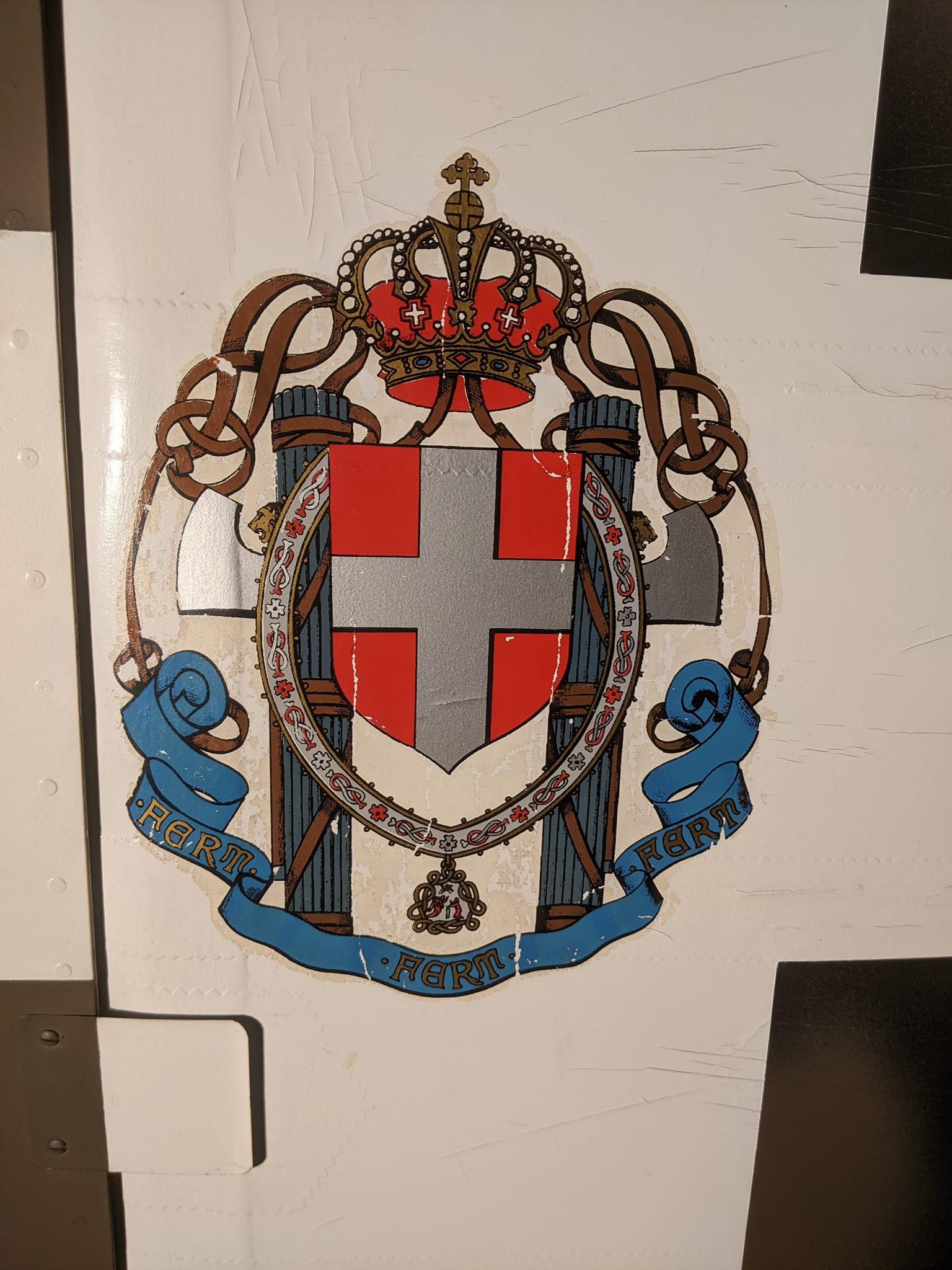

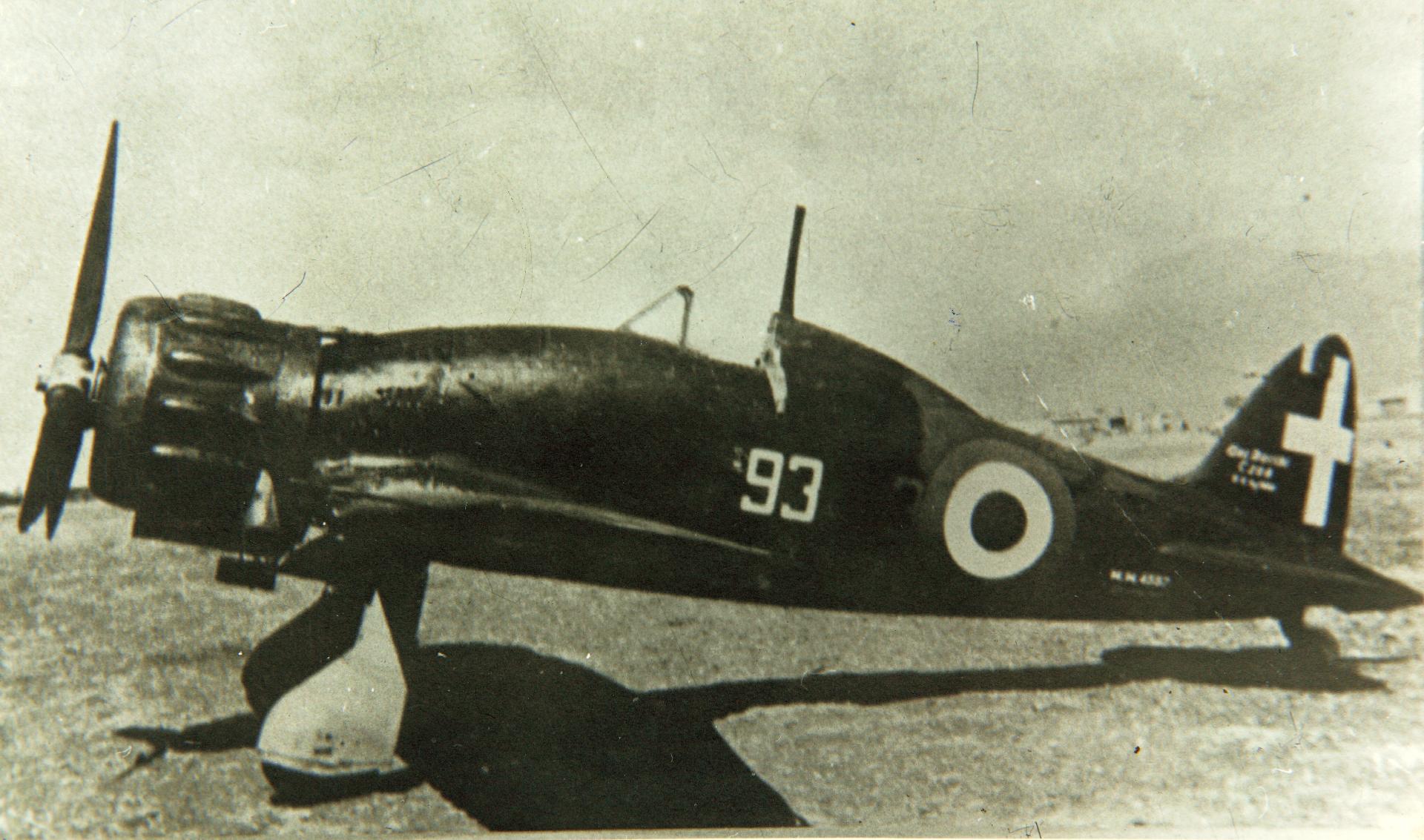

All of this painstaking work would culminate on December 12, 1991, when the Macchi C.200 Saetta was rolled out of the workshop and officially presented to the public. Although no data plate had been found on the Saetta during the restoration, it was decided to issue the airplane with the serial number MM.8146 based on production records, and the aircraft was painted in the colors of “372-5”, the markings it had worn at the time of its capture by the British in November 1942.

With MM.8146 being restored, it was decided that it would return to the United States, this time to enter the collection of the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. While the museum already had several German and Japanese aircraft of WWII displayed inside its WWII gallery, the Macchi C.200 Saetta filled a gap in the NMUSAF’s collection by adding an Italian WWII aircraft. The Saetta, however, was not the first historic Italian aircraft in the museum’s collection, for in 1987, the NMUSAF had acquired a Caproni Ca.36 WWI bomber from the Museo Aeronautica Caproni di Taliedo for its Early Years Gallery to commemorate the American aircrews that flew similar aircraft alongside Italian airmen on the Italian Front. Today, the Macchi C.200 Saetta 372-5 can still be found in the museum’s World War II Gallery, sitting beside the museum’s Consolidated B-24D Liberator 42-72843 “Strawberry Bitch”, which flew 56 combat missions flying out of North Africa and Italy to attack targets in Italy, the Balkans, and Austria while serving with the 512th Bomb Squadron of the 376th Bomb Group in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations.

Besides this example on display in Ohio, only one other complete Macchi C.200 Saetta exists today, this being MM.5311, currently on display at the Museo Storico dell’Aeronautica Militare (Italian Air Force Museum) on the shores of Lake Bracciano in Vigna di Valle, just northwest of Rome. The partial fuselage of another Saetta, whose serial number is presently unknown, is also on display at the Museo Aeronautico “Gianni Caproni” in Trento. Both of these and other surviving WWII Macchi fighters have been covered previously in this article by Luigino Caliaro HERE.

While the story of this aircraft, the only Macchi C.200 Saetta on display outside Italy, has been told and retold many times, it has often been told with certain elements missing until now. Special thanks to Jerry O’Neill, Maurizio Longoni, and Gregory Alegi for their assistance in the research for this article. For more information about the National Museum of the United States Air Force, visit the museum’s website HERE.